It was Eric Brattstrom’s interest in a far-fetched scheme to heat his chicken coop with compost that eventually landed him in the Home & Garden section of the The New York Times, but the story turns out to be a lot more interesting than how to keep chickens warm in winter.

Brattstrom and his wife Dotty Kyle built their 25-room house and barn in Warren, Vermont, seven years ago after selling a bed-and-breakfast they owned nearby. Brattstrom’s background as a commercial construction manager and the couple’s goal of reducing their use of fossil fuels were key ingredients in their plans for the new house.

Their project might have stayed strictly local, but Brattstrom ran across a newspaper article about Gaelan Brown, who taught at the Yestermorrow design/build school just down the road and had written a book called The Compost-Powered Water Heater.

One thing led to another, and before long Brattstrom had put an insulated foundation beneath his chicken coop and Brown had installed a compost heater. Brown also had written to Sandy Keenan at The Times to ask if she might review his book. When she asked where she might actually see a compost heater, Brown introduced her to Brattstrom and Kyle.

Keenan spent two days with the couple, and on December 3, 2014, the newspaper published her story about the house. It’s the tale of two early adopters who will try just about anything in the way of energy efficiency, and who haven’t stopped tinkering long after most people would have called it a day.

It had to be big

Before we can get to the many green technologies the house incorporates, there’s the matter of its size: 8,000 square feet of conditioned space, if you count the seven heated garage bays. There’s an indoor pool, the previously mentioned chicken coop, both a summer and winter home for their Kubota tractor, and a big shop.

“We did get an architect to make the drawings,” the disarmingly open Brattstrom said in a telephone interview after the newspaper published its story. “He said, ‘It’s too big, this is stupid. I’ll build it for you anyway, but it’s too big.”

The house is big because Kyle has a big family, he said, and she wanted the entire family to be able to stay in the house at the same time. That’s why there are seven bathroom and seven bedrooms.

It’s also designed with the future in mind. Both homeowners are 78 years old, and they have no plans to build again. So they included an apartment where a caregiver might someday be installed, as well as an elevator.

The upside is that 20 of its 25 rooms can essentially be turned off. Even in the dead of a Vermont winter, it never gets colder than 45 degrees in areas of the house that aren’t actively heated, Brattstrom said. Yes, he concedes, the house is way too big, but “it’s a small house for all practical purposes.”

This is no Vermont barn

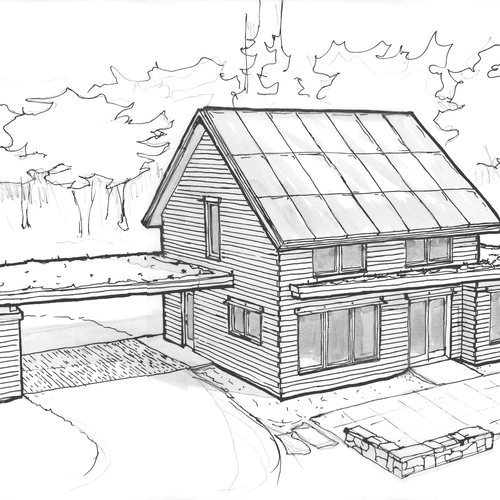

The main building consists of a barn, a two-story wood-framed farmhouse, and a connector that joins them. They chose this configuration because it resembled a typical Vermont homestead. They weren’t interested, Brattstrom said, in a “McMansion.”

The barn may look like a mostly conventional Vermont structure, but under its red barnboard skin it’s all concrete.

The couple had plenty of lumber on hand after they cleared the wooded lot and brought in someone with a portable bandsaw mill. Brattstrom used his tractor to tote the lumber to a 50-foot-long greenhouse he built on the property, but it would have taken a year to dry even under cover. Instead of waiting, he decided to use insulating concrete forms (ICFs) instead.

The ICF walls were 11 inches thick, Brattstrom said, before he added an additional 4 inches of polyiso foam insulation on the interior, giving the walls an R-value of 40. Floors also are cast concrete made with ICF forms.

The trussed roof is insulated with enough blown-in cellulose to give it an R-value of 80.

The farmhouse, built a year later when the lumber had dried, is of double stud wall construction insulated with cellulose. It, too, has R-40 walls and an R-80 roof.

When it came to choosing windows, the couple chose economy over performance. “We started thinking about all these windows,” Brattstrom said. “We have 75 windows in this house. It was going to cost us a fortune, so we got double-pane.”

He later learned he could have purchased R-5 triple-pane windows made by a company in upstate New York for less than what he’d pay for double-glazed Andersens — but that’s a thought for next time, if there were going to be a next time.

Many ways to heat the house

Vermont winters get pretty cold, but Kyle and Brattstrom have more than one way to keep the house comfortable.

There’s the 15-zone radiant-floor distribution system with a mile of PEX encased in concrete, all driven by a wood-pellet boiler. There’s the Canadian-made RSF fireplace that includes a network of ducts and fans and is capable of heating the living room, den and two bedrooms. There are the individual gas heaters in bathrooms for spot heat.

And finally there are the minisplit air-source heat pumps, a much more recent addition. Brattstrom might never have bothered with the other heating equipment had he known about these cold-weather heat pumps at the start. Brattstrom installed the system himself in two days at a cost of about $5,000.

The single outdoor compressor powers both ducted and ductless fan units inside, and the electricity they had been using to “heat a stupid pool” is now enough to heat the house.

The radiant floor was a mistake

Given the same choices again, Brattstrom would skip the radiant-floor heating.

“I wouldn’t put radiant in again,” he concedes. “I did it because I’m a plumber. When we got to Vermont, we had a bed-and-breakfast first, which had shared bathrooms and enough guest rooms to break you. I said, ‘Dotty, if you want more rooms and more bathrooms, I better get a plumbing license.'”

But they’ve discovered the thick concrete floors are slow to heat up and slow to cool down. It takes three or four days, he said, to bring a cold room up to a comfortable temperature, and a day or two to cool a room off by only a few degrees.

While the radiant floors didn’t perform as well as they’d hoped, the sprinkler system they bought from the same company that sold them the radiant floor parts, Wirsbo, has proved a “fantastic” hedge against the difficulty of fighting house fires in rural Vermont, especially in winter.

Lots of solar electricity

Their 71-panel, 12-kilowatt photovoltaic (PV) system is big by most residential standards, but there’s a lot of house to run.

They have rooftop access to the panels, allowing them to sweep them free of snow if they wish.

The solar thermal system was a disappointment

One idea that didn’t work out as well was the solar hot water system. The rooftop collectors feed a 1,000-gallon tank, but the system never performed as well as they’d hoped it would.

“We found out that thing was a pie-in-the-sky idea,” he says. “We used it for a few years, but we don’t get enough sun.”

He plans on replacing the solar collectors with more PV.

What the ideal house would look like

Brattstrom and Kyle have had a number of years to put their ideas to the test. They know this house better than most homeowners would know their own: Kyle designed it, and Brattstrom did almost all of the work in building it. (“It was not a chore in any way,” he said modestly.) That helped them keep the cost down to about $600,000.

And although another house may not be in the cards, Brattstrom has a good idea of what it would be:

- Smaller. Something no greater than 2,000 square feet, according to Keenan’s article.

- Heated primarily with air-source heat pumps, with some auxiliary heat for really cold weather.

- Really good triple-glazed windows.

- Exterior walls insulated to at least R-40.

- PV to run the house.

- What Brattstrom calls “room trusses,” which are roof trusses that incorporate an attic room.

Even though he said he won’t be building another house, he hasn’t stopped thinking about how to build a good one.

“I’m always thinking about how you can make houses that don’t use fossil fuel, because that’s what our problem is, using fossil fuel,” he said. “That’s what the idea was — to have a house you didn’t have to use fossil fuel to heat.”

Weekly Newsletter

Get building science and energy efficiency advice, plus special offers, in your inbox.

5 Comments

Heating lag time

Can anyone address how normal it is to have a three to four day lag time in heating with radiant floors? Could it be that the airtight concrete walls with super insulation were a contributing factor and the problem was not solely from the concrete floors? And did I miss the thickness of concrete in the floors? I have radiant baseboard heat in a 60 year old, nearly uninsulated home, and I wish I could retain more heat in winter. Of course, I realize that heat distributed by aluminum fins is a little different than heat distributed by concrete floors. On the other hand, it does seem to take a really long while to cool my house down if the A/C is off for any significant time.

PV for heating

Hopefully we will see more choices in the US for air to water heat pumps. Combined with water storage, it's a good solution for heat from PV. And the hydronic system is compatible with a wood boiler.

Low mass radiant floors behave significantly different than concrete ones.

Can you tell us....

...the name of the upstate NY manufacturer of the apparently reasonably-priced triple-pane windows? Thanks!

Sounds Like a Great Net Zero Bed and Breakfast

In the referenced NY Times article, that writer speculates how hard it might be to sell the home with perceived "labor intensive" chores to feed pellets, clear the 12kw PV, operate zoning systems, etc. I suggest it would be a great net zero bed and breakfast, now or in the future. I certainly would want to see it and tour the systems. The $100 sq ft construction cost leaves plenty of room for haggling if selling became important. Additional automation could also be added.

I'd like to know, also...

...about the triple pane windows.

As for the rest of it---Just. Weird. Especially the window choice.

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in