Image Credit: Mike Baird

Editor’s note: The first blog in this two-part blog series was titled How Low Oil Prices Can Be Good for the Environment.

Low oil prices make many environmentally troublesome oil drilling and oil pipeline projects infeasible as business ventures, but they do not overly encourage consumption of oil, and hardly affect efficiency at all. Here’s why:

Energy efficiency is only very weakly affected by utility prices. The same is true for oil, and therefore this year’s dramatically lower oil prices will not increase consumption by very much.

For the transportation sector, which is most relevant to oil use and price, some would question this assertion, but every study I have seen, and the data for the last year, lead me to believe that the outcome is the same: price has only a minimal effect on efficiency, and a larger but still modest effect on usage.

Looking broadly at markets for oil, the oil price trajectory for the last 40 years is flatly inconsistent with the hypothesis that price affects demand significantly.

Looking in more detail at the market’s recent response to drastically lower oil prices over the past year, the results are less than 5% increases in miles driven over the past year, and even smaller retreats in oil efficiency. Even the retreat that did occur registered as a 1% or 2% increase in fuel economy of new vehicles sold compared to increases of more like 3% per year in previous years. This absence of rebounding demand in the face of lower prices has also been noted by business analysts. It refutes the assumptions that many people have been making (but never based on serious analysis) about the supposed shift to lower-mpg cars or a return to the profligate driving habits of the past. This outcome is, however, in line with what I predicted in an earlier version of this blog in December 2014, before we had data on the response to the initial price decline of the second half of 2014.

This is remarkable: oil prices declined by more than 60% (gasoline prices declined by over 35%), and metrics of consumption behavior increased only 5%, while metrics of efficiency decreased by only 1% or 2% percent compared to previous trends (and increased in absolute terms). It is even more remarkable when one considers that other factors are causing driving and SUV sales to increase regardless of oil prices: people are making more money, especially those people in the upper income classes who are able to take driving vacations or to afford SUVs. And SUVs provide a perceived increase in energy services, so increased sales of them is not the same as a decrease in efficiency.

Efficiency is not the same thing as conservation

Efficiency — the provision of the same level of service, for example the same level of transportation access, the same size and performance of cars — must be distinguished from conservation, which is exemplified by using smaller or slower cars. America has not made much progress at conservation, especially policy-directed conservation, but we have made dramatic improvements over the years in the efficiency of cars, airplanes, refrigerators, air conditioners, and lighting, all as a result of policy, with almost no effect from energy price.

Simple economic theory may hold that high energy prices lead to higher levels of efficiency, but more realistic models, both theoretical and empirical, show that energy price has little effect on efficiency. In a mass production economy, the efficiency options available to consumers are limited to what is produced, and what is produced is determined primarily by the efficiency standards and incentives available.

This is true both in the transportation sector and in the utility sector. For example, the halogen technology used in current incandescent lamps saves 28% compared to the old technologies. It has been available in principle for decades, but only became available in the marketplace when required by federal standards. This is not just me asserting that the technology only became available due to standards, this is also the judgment of Philips Lighting.

This technology makes economic sense at current electricity prices, but would also make sense if electricity prices were less than what they are today. And the more advanced technology — LED lighting — is expected to take off when the cost of a bulb drops below some threshold, say $3, regardless of the value of the savings (which are already greater than $100).

Consumers typically don’t invest in efficiency

Most consumers do not invest in efficiency even when the investment returns 40% annually. If lower prices caused the return to drop to 30% it would not make much difference; similarly if the return increased to 50% due to higher energy prices, it would not mean that everyone would rush to invest. Recall that businesses and consumers who own homes can usually raise capital at a cost of 4%, and even credit card interest rates of 18% are far lower than the return on efficiency.

I first noticed the lack of relationship between efficiency and energy price in the 1970s when we were able to obtain information on the efficiency of commercial lighting and of home air conditioners. New York electricity prices were more than ten times higher than those in Seattle, yet a square foot of office space used more energy for lighting in New York. Air conditioner efficiency was not higher in Florida, where they operated long hours, than the national average.

More corroboration came soon afterward, when an international study showed that fuel efficiency of cars in Europe was only minimally higher than in the United States, even in the face of gasoline prices much more than double those here. European cars were smaller, so overall gas mileage was better, but for a car of the same size and performance, fuel economy was hardly different.

Arguments have also been made that North Americans drive more than other countries of comparable incomes as a result of lower gasoline prices, but more recent studies have shown that variations in neighborhood characteristics (location efficiency) explain the levels of car ownership and usage much better than price. Even this year’s slight increase in miles driven may be more of a response to a growth in housing construction in urban sprawl locations that to the fact that gas is cheaper. All of the studies I have seen of the effect of oil price or fuel economy standards on miles driven ignore the influence of location efficiency, which is a larger influence than price by a large margin.

An unintended experiment proves near-zero price response

Price elasticity studies are not reliable guides to use for predicting the consequences of energy price increases because they do not address the issue of causality, as opposed to correlation. There is a good reason why they do not: it is hard to imagine how one would set up an experiment designed to test a hypothesis (as opposed to a set of observations that the scientist does not set up). A good experiment would be to “raise the price of electricity and hold everything else equal and see how future consumption departs from the trend.”

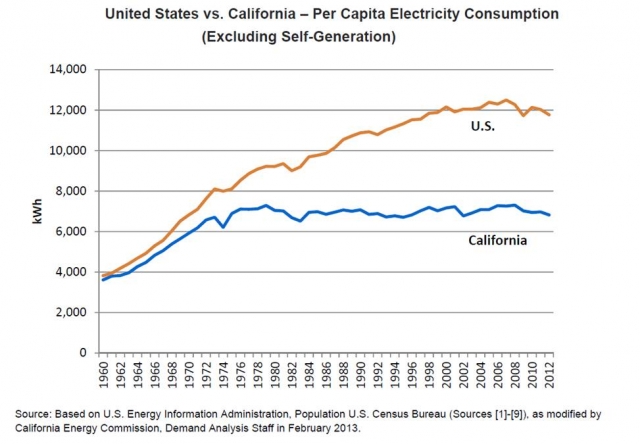

Fortunately for these analytic purposes, California inadvertently set up such an experiment, allowing us to determine how consumption changes when energy price suddenly rises by 40% and then stays that high.

As a consequence of its experiment with electricity deregulation, California reduced investment in both efficiency and new power plants, creating a serious energy shortage. To deal with the resulting blackouts, the state had to procure expensive new supplies, both conventional and efficiency, and thus to raise its electricity prices by 40%. At the same time, the shortages also prompted the state to strengthen its energy codes and promulgate new appliance and equipment standards, as well as authorizing utilities to acquire more efficiency through their incentive programs.

Thus the experiment was fortuitously well designed: to first order prices increased with no major changes in policy (the policy changes that did happen have long lead times before they save much energy), allowing us to isolate purely price effects; and to second order the policy effects would enhance the sought-after price response of lowering consumption. Thus the expected diminution of consumption would be even larger than pure elasticity would predict.

What were the results? They are so remarkable that the reader can see them in the chart at right without the need of statistical assistance. It is impossible to pinpoint when the price increase happened from looking at the blue line on the figure. And worse yet for proponents of high elasticities, the actual year of the tariff increase was the year that was followed by the steepest five-year increase in consumption in the figure.

But wait a second, is this blog trying to say that the hundreds of price elasticity studies that have been done are all (or mostly all) wrong? Not exactly: what this analysis is saying is that they are not correct for the purpose of predicting the consequences of a change in price.

And energy modeling is trying to be predictive, so for this purpose we do not care about the correlation of price to consumption but only the causative effect that price has on consumption.

The connection between price and consumption

Economists usually cannot set up an experiment such as the one described above. Instead, elasticity studies look at datasets of different places or different times, each of which is associated with a price and a level of consumption. The studies look for statistical correlations between price and consumption and the result is a measured elasticity.

Statisticians realize that correlation is not causality, and thus they do not provide the certainty needed to address the experimental question of the last paragraph. There are lots of ways that high price is correlated with low consumption that do not allow one to predict that raising prices will result in lowered consumption.

First, the causation may go in the other direction. If you have two otherwise identical areas and one has half the electricity consumption of the other, the one with lower consumption will have higher prices because the fixed costs of service have to be amortized over lower sales. (Those fixed costs will be almost identical between both systems — given normal design standards and assumptions, the same level of transmission and distribution capacity will be provided for both systems.)

Second, high price and low consumption may both be consequences of something else. For example, one data point for a gasoline price elasticity study is a gas station in Manhattan. The station has some of the highest gas prices and the lowest consumption per household. But why? The gas prices are high because the land values are high in Manhattan as a consequence of high densities of housing (or perhaps it goes the other way around: high land prices cause high densities). But in any case, high density explains both low consumption and high price.

There are many other reasons why price and consumption correlations may not imply causality. Ironically, this figure itself shows part of the problem. Even though this figure and the data behind it refute the hypothesis that there is a causative influence of price on consumption, the data for years after 2001 will show both high prices and low consumption relative to other jurisdictions. Thus, the very data that refute nontrivial price elasticities when used in the appropriate context validate a hypothesis of large elasticities when used in the context of conventional price elasticity studies.

The California experience is the closest thing to a real experiment (where the plan is to “raise the price of electricity and hold everything else equal and see how future consumption departs from the trend”) as you are ever likely to find in real-world social science.

That is a key reason why this result of near-zero elasticity is more credible for the purposes of planning about how best to reduce energy-related air emissions.

But what about economic theory?

The conditions economic theory assumes, and that are needed to make price elasticity work, are broadly missing in the real world. Saving Energy Growing Jobs lists over a dozen of the assumptions needed for theory to predict strong price response that are violated in the real world.

I recognize that the fact that energy price doesn’t really affect efficiency violates deeply held beliefs of many people. I encourage them to look at the theory and the evidence in detail, as I do in this book. Economics is not a religion; it is a science. Observing that price does not explain everything is not a heresy, but is a scientific conclusion based on evidence.

Occasionally the theory fails to take into account factors that cut the other way. Consider this: in the wake of falling oil prices, the United States was working with Caribbean countries earlier in 2015 to reduce their use of oil, in part by substituting gas-fired power plants for oil. Why is this? It is happening because of fears that tying their economies to the shaky Venezuelan economy through importing its oil increases economic risk. The point is this: in the case of these countries, lower oil prices will mean lower consumption, not higher or even the same.

Energy price does affect behavior — people are likely to keep their houses warmer if heating fuel costs less. But conservation — accepting a lower level of comfort or convenience — is not a significant part of climate pollution plans in America or anywhere else in the world. And it is a relatively minor contributor to emissions reductions, as well as being one that can be motivated by other tools than price.

Some would argue that high prices help improve the political climate for actions such as fuel economy or tailpipe carbon emission standards, or smart growth urban plans. But we have seen from California’s experience that carbon caps are even more effective at facilitating such highly effective policies far more than high prices.

Summary

Any increase in climate pollution from recent declines in oil price is likely to be small and temporary. In contrast, the setbacks to ill-advised oil production schemes, and to the budgets of countries that contribute to security problems for the U.S., will be large and long-lasting. My previous blog presents arguments for an oil pollution fee, or a carbon fee, on the grounds of economic fairness. Such a fee might also improve the market for lower-emissions fuel sources such as renewable electricity or low-carbon, low-petroleum fuels. But it will not affect consumption much.

Reducing the environmental and economic impacts of oil depends much more on the policies that this blog suggests: policies that require continually improving fuel economy as well as cleaner fuels in cars and other vehicles, that provide incentives for clean vehicles that surpass the minimum requirements, and that promote compact walkable communities that require less driving.

David Goldstein is energy program co-director for the National Resources Defense Council in San Francisco. This post was originally published at NRDC Switchboard. The first part of this blog series may be found here.

Weekly Newsletter

Get building science and energy efficiency advice, plus special offers, in your inbox.

2 Comments

Transportation is basically a fixed cost is it not?

When the price of oil goes up the consumer simply spends less on other goods/services. This is why high oil prices are always framed as "taking money out of the economy".

Efficiency standards are seen as a win from a public policy perspective because it hopefully still allows the economy to continue to expand (i.e. do more work) but at an otherwise slower rate.

Oops!

As a lifelong resident of California one couldn't help missing a major error that throws Mr. Goldstein's thesis into question.

He states: "A good experiment would be to raise the price of electricity and hold everything else equal and see how future consumption departs from the trend. Fortunately for these analytic purposes, California inadvertently set up such an experiment, allowing us to determine how consumption changes when energy price suddenly rises by 40% and then stays that high.

"As a consequence of its experiment with electricity deregulation, California reduced investment in both efficiency and new power plants, creating a serious energy shortage. To deal with the resulting blackouts, the state had to procure expensive new supplies, both conventional and efficiency, and thus to raise its electricity prices by 40%. At the same time, the shortages also prompted the state to strengthen its energy codes and promulgate new appliance and equipment standards, as well as authorizing utilities to acquire more efficiency through their incentive programs."

This entire statement is so wrong headed it is hard to know where to start. The extreme price rises due to deregulation in the late 1990s had nothing to do with under investment in energy production infrastructure. It simply had to do with Enron taking plants off line during peak usage hours due to "maintenance" in order to create an artificial shortage. This is so well known throughout our state that it begs the question whether the author does not know this, or whether he is counting on the ignorance of residents' of other states to not call him on it. It has to be one of the two.

Either conclusion is damning. I really wanted to believe this article because it supports things I agree with. But such a major misrepresentation of recent history as described above really discredits this article.

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in