Image Credit: Ron / CC BY-ND 2.0 / Flickr

The calls and emails arrive as often as several times a week from people with concerns about drinking water. Some of the callers — who include homeowners, architects, and builders — want to know why their water smells like gasoline. Others want to know which kinds of pipes to install to minimize risks of exposure to hazardous chemicals.

Purdue University environmental engineer Andrew Whelton has spent more than a decade studying how pipes that carry drinking water to our homes, schools, and business places can affect water quality and health. But still, he struggles to answer their questions, particularly when it comes to a new generation of plastic piping material called cross-linked polyethylene, or PEX.

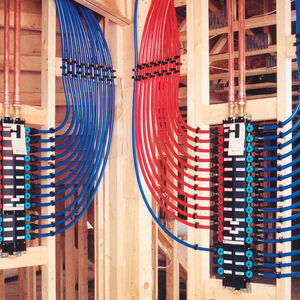

Used in more than 60% of new construction projects in the United States — according to the Plastics Pipe Institute, the pipe industry’s major trade association — the flexible tubing is appealingly cheap and easy to install. But data are still accumulating on how it affects the water that flows through it, Whelton says, and certification standards may be failing to test for compounds that affect water quality. That leaves consumers in the dark.

The latest research out of Whelton’s lab has revealed a variety of compounds that can escape from PEX pipes, potentially causing drinking water to smell or taste bad. His group is also finding significant variations in what leaches out of PEX pipes, not just across brands but also among products of the same brand, and even from batch to batch of the same product — a confounding list of unknowns and potential concerns that makes it complicated to give advice to consumers who want safe plumbing materials.

The plastic pipe industry stands by the rigorous system of plumbing codes and certification standards that determine which pipes can be used in construction. But even as the water crisis in Flint, Michigan, has drawn attention to the hazards of lead pipes, few independent researchers other than Whelton and his colleagues are studying the implications of PEX in the United States.

“I am a homeowner who has had to replumb his house before, and I am frustrated about the way things are,” says Whelton. “We don’t have information about the chemicals that are leaching out of these pipes, and because of that, we can’t make the decisions we want to make.

“There have been marketing campaigns that imply we understand the safety of these products,” he adds. “In fact, we do not.”

Unsettling unknowns

By now, anyone who has fretted about the health and environmental complexities of plastic has found ways to limit its presence in their lives — by switching to stainless-steel water bottles, buying canned foods made with BPA-free linings, or toting ceramic coffee cups. But plastic pipes have lurked under many people’s radar, even as they have become an increasingly popular alternative to copper for delivering drinking water into homes and buildings.

Although copper remains common inside buildings, there are compelling reasons why new projects frequently use PEX. Price is one major draw: PEX can be a good 75% cheaper than copper. In one 2013 survey of plumbing supply stores in southern Alabama, copper cost $2.55 per foot compared with 48 cents per foot of PEX. That can add up to thousands of saved dollars over the course of a house project.

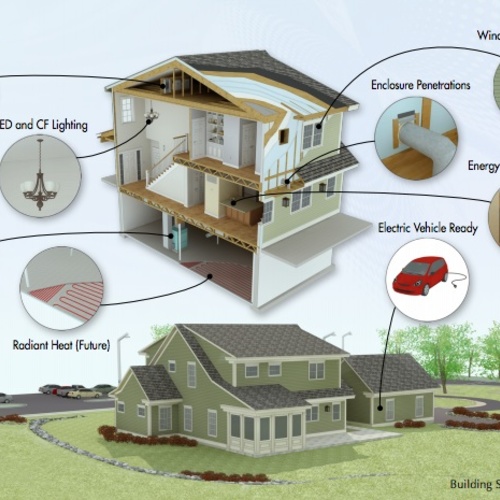

PEX is also lightweight, flexible, easy to transport and install, and built to be long-lasting. Like copper, it can carry hot water without melting. There may even be environmental benefits: production, use and disposal of PEX products uses far less energy and produces less carbon dioxide than copper. As part of its Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) rating system, the U.S. Green Building Council offers design credit for PEX piping, since PEX avoids some of copper’s other flaws, too — including the potential for corrosion and related health risks, such as liver damage and kidney disease.

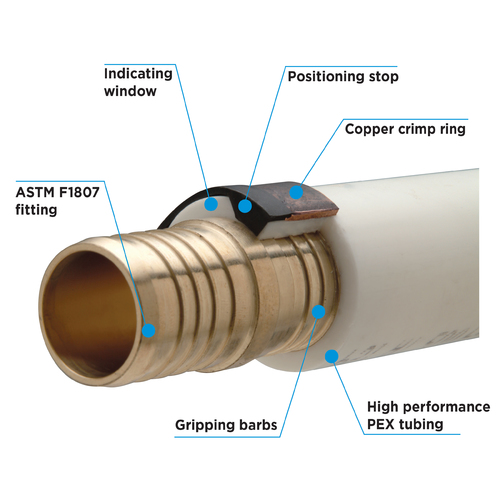

PEX is tested rigorously before it can be certified to comply with plumbing codes, says Lance MacNevin, director of engineering in PPI’s Building & Construction and Conduit divisions. Embedded in those codes, MacNevin says, are requirements that piping meet certain standards set by the global standards organization ASTM International. And within the ASTM standards are yet more standards set by NSF International, an independent non-governmental public health and safety organization that creates specifications for pipes made to carry drinking water.

NSF has tested some 1,700 types of chemicals and compounds in water that comes into contact with plumbing components and set a standard called NSF/ANSI 61 to make sure they are below levels that would cause health concerns set by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency or Health Canada, says Dave Purkiss, general manager of plumbing products at NSF International. Plumbers and plumbing inspectors are trained to understand the codes, MacNevin adds. And third-party certification involves stringent quality control, random plant inspections and annual monitoring.

“The existing system of codes, standards, and certifications is extremely rigorous,” MacNevin says. “Our position is that plastic is the preferred solution over all other materials.”

Whelton’s research, though, has flagged some unsettling unknowns about PEX pipes, starting with the lack of publicly available information about what is actually in them — with a wide variety of possibilities. PEX can come in one of three categories, called PEX-a, PEX-b and PEX-c. In some applications it’s layered with metals such as aluminum. Overall, consumers can choose from at least 70 different brands that have been certified by NSF/ANSI 61.

So far, studies in Europe and the U.S. have revealed at least 158 contaminants in water that have been associated with PEX, and scientists are still trying to get a handle on where they all come from and how they might affect people. As part of one ongoing effort, an open-data project called Quartz has analyzed patents, safety data sheets, and other sources to document about a dozen general components, solvents, and other substances in PEX, some that could be hazardous at high enough levels, though the doses actually reaching people still need to be evaluated.

MacNevin says it would take extraordinarily high exposures — much higher than someone could get from a pipe — to reach those hazardous levels, and some of the data used in Quartz also appeared to come from companies that don’t make PEX water pipes. Other recent research out of Whelton’s lab, adds Purkiss, has revealed contaminants at levels far lower than NSF standards.

“We’re just trying to map what the substances are that can be the causes of what [Whelton] is finding in water,” says James Vallette, research director at Healthy Building Network, an organization focused on reducing the use of hazardous chemicals in building materials, which is collaborating on the Quartz project. “We’re not willing to make health statements.”

Health implications are not fully understood

Possible health implications are particularly hard to pin down because different types of PEX leach different materials, and, without routine disclosure of ingredients hidden within trade secrets or of specific NSF testing results, it is impossible for consumers to know what they’re getting.

In a study published this spring in the Journal of the American Water Works Association, Whelton and colleagues tested eight varieties of PEX over 28 days and found extensive variability in the kinds of chemicals that came out of each. Three of the eight released enough assimilable organic carbon to exceed the levels needed for harmful microbes to grow inside pipes.

The study also found evidence that still-unidentified chemicals may be contributing to odors associated with PEX pipes, along with compounds called ETBE and MTBE that have been identified in previous work. And those smells can make water unpalatable. An analysis reported in 2014 by Whelton’s group found odor levels that exceeded EPA limits in water that flowed through six brands of PEX. Those odors were not there before the water went through the pipes.

Many questions about PEX remain unanswered, agrees Andrea Dietrich, an environmental engineer and water-quality expert at Virginia Tech in Blacksburg. Does water need to be treated differently before traveling through plastic pipes than before flowing through copper? And should protocols vary depending on a region’s geology, which can alter water’s mineral content and subsequent reactivity? “Those factors haven’t been explored,” she says. “I just don’t think the long-term data are out on PEX pipes.”

Information, please

Adding to the complexity of evaluating PEX, performance also seems to depend on how, when, and where the pipes are used. In a study published last year, Whelton’s team found that a cleaning method used on newly installed PEX pipes alters resulting chemical levels and odors in water. And those results can change over time. In data Whelton will present at the AWWA conference in June, Whelton’s team analyzed two brands of PEX for two years after installation. They found few changes in one brand, but there was a lot more leaching out of the other by the end of the study than at the beginning.

And while current NSF/ANSI standards are extremely valuable, Whelton would like the guidelines to specify more chemicals, including some that make water smell bad enough to be undrinkable (even if they still meet health standards) and others that could allow illness-causing bacteria to flourish. He’d also like to see routine testing for chemicals at more than one point in time. Drinking-water standards in the U.S. cover only the quality of the water, not performance of the material, he adds, and there is no federal system to issue recalls or safety alerts.

Compliance with standards also doesn’t guarantee that pipes are safe, and history has made it clear that pipe choices can be catastrophic. That history includes a major class-action lawsuit over polybutylene pipes, a type of plastic used in residential and commercial projects for nearly two decades before finally getting linked to high rates of failure and catastrophic leaks in the 1990s. “I want to make it clear that we are not against the industry,” Whelton says. He just wants to make more information available to consumers.

The consumer is the ‘beta tester’

Water is generally safe in the United States, Dietrich adds, and she usually drinks from the tap wherever she goes, even when it emits certain benign smells. But she’s frustrated by a system that makes it easy for new products to slip into the market without extensive analyses. “We’re not proactive about protecting drinking water, and that includes rigorously testing materials used in plumbing,” she says. “The consumer ends up being the beta tester.”

Better advice may be coming soon. When his new results come out this summer, Whelton hopes to be able to give homeowners more details about plumbing safety and specific products. “We’re heavy into getting data,” he says. “Once we get all the data, we’re going to turn and do educational efforts.”

Emily Sohn is a freelance journalist in Minneapolis whose work has appeared in The Los Angeles Times, Discovery News, Smithsonian, U.S. News & World Report and other publications. This post originally appeared at the website Ensia.

Weekly Newsletter

Get building science and energy efficiency advice, plus special offers, in your inbox.

22 Comments

PEX

When a plumber suggest copper it's like a politician saying it's for the children. In either case you'll spend more and have less to show for it.

Properly done PEX with brass fittings, copper manifolds and pressure balanced is a winning combination. Freeze protection is icing on the cake. As far as chemicals, the making of copper isn't that good either.

I have PEX all through out my

I have PEX all through out my home and have not had any issues with smell or taste.

To add to what Stephen said, if it does freeze (not joints or fittings) it generally will not break. I have first hand experience as my domestic lines have frozen nearly every year. I have composite and metal manifold with steel clamps over brass fittings through out.

It is easy to run and generally inexpensive.

Off the subject but...

I was told to only use copper ties with copper pipes and fittings--unlike what's shown in the first picture.

What about research from the EU?

PEX has been in-use in the EU for decades. That was one reason I decided to use it in my new house. After having to go through a polybutylene-to-copper conversion on my old house, I wanted to make a good decision on the new project. Oh, well...

Antonio

They make special fittings to go from sweat for copper to crimp for PEX. They have all sorts of combinations for the different types of PEX crimps and copper, including compression fittings.

They also make extremely cheap snap on metallic 90's to help guide and hold the PEX in-shape for a 90 degree bend.

A data point: bad taste with PEX-a

Just to balance out the comments reporting no problems, I'll report that our water tasted terrible after installation of PEX-a pipes running to the kitchen sink. Flushing a gallon or so down the drain each time we drew a pitcher of tap water solved the problem.

PEX-a taste

We put in PEX-a Uponor tubing about 8 years ago, and again about a year ago (for a combination fire sprinkler system that drinking water flows through). In both cases, it has taken about a year for the plastic taste to go away. PUR filters on the faucets gets rid of the plastic taste, and is extra protection in case the studies do find any harmful levels of substances.

Pex B

The article cites an adoption rate of 60% in new American houses. Here in BC it is probably closer to 95%, and almost all Pex B. I've never experienced or heard of a taste or smell problem.

I hope there isn't a problem with chemicals leaching from Pex contaminating water, but from the equivocal tone of the article it is unclear if we should worry or what we should worry about. My takeaway was "Someone is thinking of looking into something for something sometime".

Oh... and someone needs to get that framer a level.

Response to Malcolm Taylor

Malcolm,

My guess is that the worker who was tightening the anchor bolts whacked that stud to one side to make it easier to swing his wrench. When he was done tightening the anchor bolts, he forgot to whack the stud back to where it belonged.

There was a lot of innunendo in the article and as

previously mentioned by Steve the EU has used this product for decades. I'm surprised the article didn't mention it, but then again doing so might have made the topic moot.

Response to Malcolm and Chris

Malcolm and Chris,

If I understand your points correctly, I agree with you. The author of this guest blog, Emily Sohn, is saying, "It would be good to have more information on these issues." The same can be said about many topics, including (for example) global climate change -- or, for that matter, almost any topic of scientific interest.

The statement, "It would be good to have more information on these issues" is quite different from, "We have data showing worrisome human health outcomes related to the use of PEX."

Martin

Like the plumber who only protected half the lines with plates where they go though the framing. Must have been a Friday afternoon job.

Europe may not be evidence of safety.

Felt I had to create an account just to clarify a few things. Both the author of the article and some commenters seem to have a few misunderstandings of the material and potential concerns.

For those say that PEX has been used in Europe for decades with no issues, that's both true and somewhat misleading. In Europe they tend not to use chlorine for sterilization of municipal water, and polyethylene is well known to degrade in the presence of chlorine. Chlorine is extensively used in water here in the US. Now, cross linking (the X in PEX) increases resistance, but it's incomplete, and varies with process (PEX-A, B, C) and batch. Further, while there are standards for chlorine concentrations in municipal water, some municipalities have a habit of overdoing it. Where I live, local water reports have occasionally put chlorine levels at more than double the required, though it varies over time. Varying chlorine levels may be part of what's making research on this topic somewhat tricky.

All together, it's not evidence of a problem, but it's also enough to make me scratch my head about the long term safety and durability of PEX pipe on a municipal water supply. On a well, I'd have far fewer concerns - but from a plastics chemistry viewpoint, chlorine is problematic. You can, of course, filter at the tap for drinking - but that still leaves a potential concern about durability after a couple decades of exposure, and the unknown of, say, contact via bathing.

I'm currently working on a house for a family where one member is positive for a BRCA mutation, increasing their (and potentially their children's) susceptibility to environmental carcinogens well above and beyond the risk of the general population. It has been exceptionally difficult to make material decisions due to the general lack of decent data, and 'PEX, Copper, or Polypropylene?' has been among the most vexing.

Interesting links; EU and Chlorine usage for muncipal water

http://www.waterandhealth.org/newsletter/new/summer-1998/disinfection.html

http://www.lenntech.com/processes/disinfection/regulation-eu/eu-water-disinfection-regulation.htm

Chlorination in Europe

It looks like Chris M's links contradict Chris B's statement that "In Europe they tend not to use chlorine for sterilization of municipal water."

Declining Chlorination

I am a small water systems operator and oversee two community water plants. While chlorine is still the mainstay, the trend in North America is to replace it with micro-filtration and UV disinfecting. The amount of chlorine used is essentially just to maintain a residual level in the lines far from the plant. Over the last decade we have reduced the amount we use by a factor of ten, and I could see its use disappearing entirely within a few years.

not quite that simple

While I did generalize a complex reality in the interest of length, that data is almost 20 years old, and one link simply reproduces the data of the other. It also doesn't address the timing, frequency, concentration, or methods to reduce chlorination byproducts, all of which can and do result in general differences between EU and US water systems. The point was: PEX stability in Europe isn't directly comparable to the US.

See the 2007 article here (which is itself out-of-date; chlorine use is declining all over, though use is much greater in the US and that will likely continue for some time, with regional variations):

http://repository.tudelft.nl/islandora/object/uuid%3A012dcc1c-52f0-40b6-ac04-70afe9b3c494?collection=research

"given the concerns about chlorination by-products,

there is still widespread, but decreasing, use of prechlorination

in the USA. While the use of ozone as a

primary disinfectant and chloramines as a secondary

disinfectant is increasing, chlorine remains the most

common post-disinfectant."

and:

"Europe uses various alternative disinfectants for

drinking water disinfection (Table 3) but the practice

is not homogeneous. France, for example, mainly

uses ozone. Italy and Germany use ozone or chlorine

dioxide as primary oxidant and disinfectant.

In most southern European countries (e.g., Italy,

Spain, and Greece) and the United Kingdom (UK),

chlorine is added for residual disinfection. The UK

is one of few European countries that use chloramines

for residual disinfection in the distribution

network and for the lowering of DBPs (Spain also

uses chloramines for disinfection occasionally).

The use of chloramines in France is presently prohibited.

Generally, in central Europe (e.g., Berlin,

Amsterdam, Zurich, Vienna), there is no distribution-

system residual, a practice permitted by promoting bio-stability."

Reply to Chris B

Right, so it appears that Europe is ahead of North America in reducing it's use of chlorination, and it is doing so because of it's concerns over worrying residual byproducts like THMs. But these byproducts are the result of treatment, not any interaction with pex piping, and this reduction of chlorine use in Europe is a fairly recent thing.

So we are still left with a long history of pex use with no apparent smoking gun, and the same jurisdictions in Europe that have deliberately tried to reduce their dependance on chlorination continue to allow the use of pex in water distribution systems.

I'm still at a loss to see how all this would allow us to draw any inference that pex poses a problem. I'm not saying it doesn't, it would just be helpful to see something that would lead us to believe it was likely.

Reply to Malcolm

For the time period that PEX has been in use, Europe has often (again, broadly generalizing) used liquid chlorine differently and/or at levels lower than common even today in the US. it's one thing to use chlorine as part of the initial disinfection, it's another to use it for disinfection in the distribution network where it will reach consumers (and their plumbing) in higher concentrations.

My point is simply that the US and Europe are not directly comparable in this regard, and that we just don't have good data on long term use of PEX piping when exposed to chlorinated water of the sort commonly found around US municipalities, where "add extra stuff that kills the bad stuff, just to be safe" is the usual strategy. I haven't seen anything to indicate that chlorine use will broadly go away anytime soon in the US.

Now, as far as the cause for concern - without good long term data, the best we can do is look at the chemistry, inferring from short term effects at higher concentrations, which is part of what the researcher mentioned in the article is doing:

http://ascelibrary.org/doi/abs/10.1061/%28ASCE%29EE.1943-7870.0000366

http://ascelibrary.org/doi/abs/10.1061/%28ASCE%29EE.1943-7870.0000147

Basically, we know that Polyethylene is susceptible to attack by oxidizers like chlorine:

"Oxidizers are the only group of materi-

als capable of chemically degrading

polyethylene. The effects on the poly-

ethylene may be gradual even for

strong oxidizers and short-term effects

may not be measurable. However, if

continuous long-term exposure is

intended, the chemical effects should

be checked regularly."

from here:

http://www.cdf1.com/technical%20bulletins/Polyethylene_Chemical_Resistance_Chart.pdf

We know that cross linking (that X again) generally increases chemical resistance, and that PEX-A, B, and C are cross linked to varying degrees by different methods. PEX-A has the highest degree of cross linking (~85%), then B, then C. But PEX-B has better resistance to oxidation. Note terms like "better" and "increases", not "perfect" and "completes." Cross linking doesn't magically make Polyethylene totally hydrophobic, it's an improvement.

Is that increased resistance sufficient? And sufficient for how long? We know there is a pathway for degradation, but it's extent is poorly understood. It's the fact that there's a pathway at all.

Reply to Chris B

delete

I've wondered lately if the

I've wondered lately if the most cost effective combination would be PEX combined with a large whole house filter to reduce overall chlorine as it comes into the house:

http://www.multipure.com/aquasource.html

Plus point of use filters for drinking to filter out any further contaminants.

Alternately, 304 stainless piping and fixtures is an option as well but looks to be even more expensive than copper.

Polypropylene

Polypropylene (green pipe) is probably the long term answer, although it to could have questions but considering nearly all retail drinking fluids not from the tap come in Polypropylene bottles, it's fairly well tested.

Fusion welding is also pretty sweet...

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in