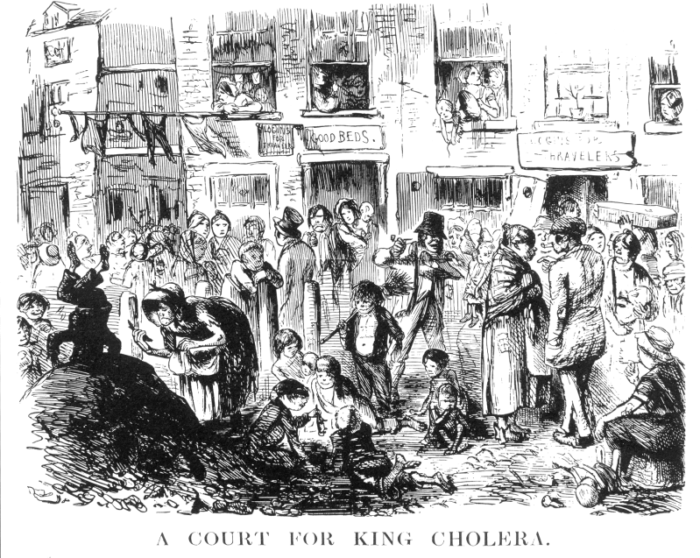

Stuffy homes are unhealthy homes, while homes with plenty of fresh air are healthy. That’s been a commonly held belief for at least 200 years. In the mid-19th century, the connection between ventilation and human health was championed by sanitarians, a group of health experts who blamed the spread of bubonic plague and cholera on “miasma.”

According to Michelle Murphy, the author of Sick Building Syndrome and the Problem of Uncertainty, “Ventilation engineers had previously promoted the mechanical supply of ‘fresh air’ in the name of healthfulness, not comfort. The fight against foul air, excess carbon dioxide, and miasma … had allied ventilation engineers with public health reformers, called sanitarians, who sought to improve the living conditions of the worthy laboring poor by … legislating standards for fresh air in tenements, schools, and factories.”

The miasma theory of contagion was disproved in the 1860s. However, the connection between ventilation and human health is still trumpeted by various organizations, including “healthy house” groups and fan manufacturers. For example, marketing materials from Broan, a fan manufacturer, claim that “microbial pollutants like mold, pet dander and plant pollen along with chemicals such as radon and volatile organic compounds (VOCs) create a toxic environment in your home.”

Similarly, a document posted on the website of the Healthy House Institute declares, “Ventilation is a critical component for home durability and occupant health.”

Since experts have posited a connection between mechanical ventilation in homes and human health for the last 160 years, perhaps it’s time to ask two questions:

The answer to the first question is no, not really. And the answer to the second question is an emphatic…

Weekly Newsletter

Get building science and energy efficiency advice, plus special offers, in your inbox.

This article is only available to GBA Prime Members

Sign up for a free trial and get instant access to this article as well as GBA’s complete library of premium articles and construction details.

Start Free TrialAlready a member? Log in

42 Comments

More info...Plz

Great write-up, thank you. Your link to “Healthy Efficient Homes: Research to Support a Health-Based Residential Ventilation Standard” did not work.

A couple of questions:

1. What would be the best suggestion on ventilation strategies for homes in the Deep South with a high-humid climate, other than ERVs and a separate de-humidifier as part of the HVAC system?

2. What would be the best suggestion on ventilation strategies for homes in the middle of Downtowns, where buildings, transportation and density pollution is so much higher?

In conjunction with air sealing?

Thanks for the in depth look at "health & ventilation rates" based on the available facts. As we move into a period that promotes higher insulation values and lower exfiltration rates, ventilation becomes an area where we need a better understanding and practices.

During this past code cycle here in Washington State, the states (TAG) Technical Advisory Group had accepted that 3ACH50 was possible for new construction and was moving in favor of adoption. A later discussion about current ventilation practices and knowledge brought the airsealing issue to a stop. It was felt that for one to improve, the other needs to be checked and improved also.

One of the reasons I'm asking is that the home evaluation/insulation /airsealing programs seem to be gaining ground. It going to take good ventilation to keep these homes healthy. Creating tighter homes only to ventilate therm with exhaust only fans and, at times, no make up air path, seems like falling short of the goal.

In researching this subject did you come across anything that could shed light on homes that had make up air paths vs those that don't? I thinking that make up air is one significant difference between commercial and residential applications for existing buildings. Residential make up air coming from a crawl space would contain different pollutants than air through window vents (even though I think they are a silly idea).

Response to Armando Cobo

Armando,

Q. "Your link to ‘Healthy Efficient Homes: Research to Support a Health-Based Residential Ventilation Standard’ did not work."

A. Bummer. The link worked yesterday. Someone at the EPA evidently just pulled the document from the EPA website.

Q. "What would be the best suggestion on ventilation strategies for homes in the Deep South with a hot-humid climate, other than ERVs and a separate dehumidifier as part of the HVAC system?"

A. I recommend that every home include a mechanical ventilation system that can ventilate at the rate specified by ASHRAE 62.2. Since most southern homes include air conditioners that deliver air through ductwork, the most common type of ventilation system in the South is a central-fan-integrated supply ventilation system. It's also possible to install an HRV or ERV with dedicated ventilation ductwork.

As my article notes, during hot, humid weather, it's a good idea not to overventilate. It's up to each family to figure out what that means. In some climates -- Houston is the classic example -- you may need to install a stand-alone dehumidifier to keep indoor RH in a healthy range during the swing seasons (spring and fall).

Q. "What would be the best suggestion on ventilation strategies for homes in the middle of downtowns, where buildings, transportation and density pollution is so much higher?"

A. If the home has a supply ventilation system, make sure that the system has a filter, and check the filter regularly so that the filter can be changed or cleaned as required. If the home is near a busy intersection or highway, I would turn off the ventilation system during rush hours.

Response to Albert Rooks

Albert,

Q. "In researching this subject did you come across anything that could shed light on homes that had make-up air paths vs those that don't?"

A. As you probably know, there are three types of ventilation systems: exhaust-only, supply-only, and balanced systems. Your question applies to exhaust-only systems, since the other two types of ventilation systems provide ducted outdoor air.

According to the best available evidence, exhaust-only systems can work well, especially in small homes with an open floor plan. There is some evidence that the distribution of fresh air can be a problem with this type of system; however, we need far more research before we can conclude that there is anything wrong with exhaust-only systems.

There is evidence that passive air inlets are usually unnecessary with exhaust-only ventilation systems. I discuss many of these questions in my article, Designing a Good Ventilation System.

Q. "Residential make-up air coming from a crawl space would contain different pollutants than air through window vents (even though I think they are a silly idea)."

A. You make a good point. That's why builders need to have a whole-house understanding of building science principles. It's a good idea to pay attention to air sealing when designing your crawl space. A good conservative approach to crawl space conditioning uses an exhaust fan in the rim joist and a grille in the floor between the upstairs (conditioned) space and the crawl space; this approach results in crawl space depressurization. More information here: Building an Unvented Crawl Space.

But...

But here are my doubts: in a Hot-Humid climate I always spec high efficient forced-air systems with an additional de-humidifier and an ERV, but I’m always wondering if I’m highly increasing the energy usage unnecessarily, or if I just need to see it as a “must” expense; not any different than people up north who need to install 4’ of rigid foam outside the bldg enclosure or 10” under the slab. I don't think slowing outdoor fresh air is the answer... don't want a moldy or damp house. Any thoughts?

Response to Armando Cobo

Armando,

I believe that a responsible residential designer or builder should include ventilation equipment capable of ventilating a home at the rate specified by ASHRAE 62.2.

Once the home is completed, however, it's up to the homeowner to decide how to operate the equipment. You can provide advice, but you can't control how they operate their fans.

Some families have lifestyles that don't require a lot of ventilation. Other families have lifestyles that require more ventilation.

We are all awaiting more research on these issues, Armando.

Thanks

Good points, I guess I'll sleep good from now on...

Free information

There is a bunch of free information from the EPA in PDF format at http://www.epa.gov/iaq/pubs/index.html#residential air cleaning devices

Response to Armando Cobo

Armando,

Thanks for providing that link. Here is the bottom line, according to the EPA:

"The best way to address this risk [the risk of indoor air pollution] is to control or eliminate the sources of pollutants, and to ventilate a home with clean outdoor air. The ventilation method may, however, be limited by weather conditions or undesirable levels of contaminants in outdoor air. If these measures are insufficient, an air cleaning device may be useful. While air cleaning devices may help to control the levels of airborne allergens, particles, or, in some cases, gaseous pollutants in a home, they may not decrease adverse health effects from indoor air pollutants."

Ventilation rates and health

Martin,

It is an elusive relation: does better indoor air quality lead to improved health? There have been many studies of indoor air quality and ventilation rates. Most show that higher rates, within reason, reduce indoor air pollutants and should lead to better IAQ. There have been some attempts at making a better correlation between good IAQ and occupant health. There was some work in Canada's far north where most infants have terrible bouts of respiratory illness. Despite the problems of doing research in the north, and a relatively small sample, there were some encouraging results at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19719534 Another excellent project was looking at the ventilation rates, IAQ, and respiratory health of over 100 asthmatic children in Quebec City. Again, more ventilation led to improved IAQ but the medical improvements were more nebulous. This study is still being published here and there but here are references to some of the papers: http://archive.nrc-cnrc.gc.ca/eng/projects/irc/air-initiative/fieldstudy.html

It has been difficult to find the best number to insert into standards such as CSA F326 and ASHRAE 62.2. I think the research has shown that air exchange rates (including mechanical ventilation) in the order of 0.3 ACPH for many houses (or 30-60 L/s) result in most indoor pollutants being reduced below guideline levels. This seems like a reasonable goal until we get the expensive health research completed.

Response to Don Fugler

Don,

Thanks for providing the two links. The abstract of the Inuit study reports that "Use of HRV, compared with placebo, was associated with a progressive fall in the odds ratio for reported wheeze of 12.3% per week ... Rates of reported rhinitis were significantly lower in the HRV group than the placebo group in month 1 ... and in month 4 .... There were no significant reductions in the number of health center encounters."

My girlfriend, Dr. Karyn Patno, is a pediatrician who worked for years in a Yup'ik community (Bethel, Alaska). She has told me about the frequent respiratory problems of Yup'ik children, which sound similar to the symptoms reported in Inuit communities. The study you linked to shows significant results, although it is unclear whether the findings are broadly applicable in other cultural settings or other climates.

It sounds like the Quebec City study is ongoing, and I was unable to find a paper reporting any medical data. I'll take your word for it that "the medical improvements were more nebulous."

I agree that 0.3 air changes per hour -- a ventilation rate that is close to the standard that has been floating around for 24 years (ASHRAE 62-1989) -- "seems like a reasonable goal until we get the expensive health research completed."

Passive heat recovery system

A very clever passive heat recovery unit has just come onto the market called Ventive here in the UK - which means, unlike MVHR, zero electrical input and no noise. And a lot less space. Too early to have any feedback from installations but it sounds genius - especially with the move to air-tight Passivhaus standards and keeping embodied carbon low. Not sure about costs, but you can find info about them here: http://www.ventive.co.uk/

If anyone knows of any other passive heat recovery system - or research papers - I'd be grateful to hear about it.

Sick building syndrome study telling, but...

Joe L's assertions about studies only showing issues with industrial pollutants, not residences or office buildings, seems contradicted by the SBS study showing an inverse relationship between ventilation rates and SBS in office buildings. It seems that if one could put a price on SBS and on ventilation, one could then easily calculate the most cost-effective rate of ventilation.

Of course, studying buildings with low-ventilation and low SBS rates might be informative as well.

Response to Dustin Harris

Dustin,

I won't presume to speak for Joseph Lstiburek, who may well agree with you.

However, I can think of several ways in which office buildings differ from homes:

1. Most office buildings have more people per square foot than most U.S. homes.

2. Most office buildings have equipment (for example, copy machines) that isn't found in most U.S. homes.

3. Many (perhaps most) U.S. homes are empty during the day and occupied at night -- the opposite pattern from most offices.

4. The cleaning products used in offices may differ from the cleaning products used in homes.

We need more research on these issues.

Joe would be proud of me; I'm

Joe would be proud of me; I'm ventilating at an average of

about 0.1 ACH in a volume of 15,000 cubic feet. [This also

answers the question over in the "Maine" thread.] That's the

lowest the Fantech will run, and keeps the CO2 at a more than

adequate 700-800 ppm. I've shut down the ventilation on a

few occasions just to see how quickly my own "miasma" builds

up; it takes almost 24 hours before it's at what we'd

consider unhealthy levels, and opening a couple of windows

or going to high-ventilation zaps it right back down. No

appreciable rise in humidity just from respiration.

So I've got a fairly decent handle on how much ventilation

is needed for my own situation. I agree that monitoring CO2

is a convenient indicator, as well as humidity in places

where it tends to accumulate faster, and I'd love to hear

of more building maintainers routinely watching that stuff.

I wouldn't want to run ventilation in hot humid weather unless

that air is being actively dealt with -- whole-house dehum, a

heat-pipe setup, or sent into the main air-conditioning system

when we're *certain* that it's running. That's why I threw

together that "HRV integration" stuff for the HVAC -- that's

for summmer, and if there are times when no actual cooling is

needed but the outdoor air is yuckier than I could possibly

cause my indoor air to be, the HRV will remain inactive.

_H*

Cats & Dogs, HEPA Filters, Sinusitus, Measuring Air Changes

It's becoming obvious that trying to correlate a minimum residential ventilation rate with health is impossible.

Just a few additional complications worth mentioning:

1. You can't measure the natural infiltration rate of any house accurately. Therefore all the homes in a study would have to be tight enough to make the natural ventilation negligible compared to the forced ventilation. Since you would have trouble guaranteeing that all the windows and doors are closed all the time, this is impractical. Even a tracer gas test would be meaningless because of variable outdoor conditions and house geometry. Food for thought: http://www.buildingenergysolutions.com/pdfs/bdtest.pdf

2. "Health" is relative. Dr. Rebecca Bascom, in her comments on the ASHRAE 62.2P, said, "health varies wildly among people; and susceptibility to health problems varies widely." Maybe you could identify an minimum ventilation rate for sinusitis, but that would be different than asthma.

3. Some studies may indicate that dirty kids (breathing dirty air) may be healthier adults, quoting from the internet: "One study of Amish children who live and work on farms, published in the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, suggested that early-life exposure to allergens may prevent the immune system from developing allergies." Allergists inject you with the allergen in an attempt to cure your allergy. Isolating yourself from allergens by having clean air could make your allergies worse.

4. Is re- filtering indoor air with a HEPA filter worth doing?

5. If you actually comply with ASHRAE 62.2, even using an ERV, your indoor air can be uncomfortably dry during very cold weather. Bumping the humidity back up to 35% with a humidifier will cause condensation and mold on most double pane windows. High performance windows will solve this one.

6. House pets can cause health problems that ventilation can't prevent.

7. Maybe healthy air can be manufactured from stale air with an oxygen concentrator and an ion generator? http://www.myvillagegreen.com/brands/sinus-survival/sinus-survival-air-vitalizer.html

Response to Kevin Dickson

Kevin,

Thanks for your perceptive comments.

Concerning point #2 -- "Health" is relative: Public health researchers are familiar with the study of correlations between a variety of factors and human health. Some factors -- like tobacco smoking or lack of exercise -- show a very strong correlation with health outcomes. These correlations jump right out when you look at the data.

Residential ventilation rates don't fall into the same category, it seems to me. If there is a correlation between residential ventilation rates and occupant health, the correlation is likely to be very weak.

NESEA workshop

I haven't checked to see if NESEA has posted workshops from BE13, but Lew Harriman and Bill Rose gave a great one called "Should Code Regulate Humidity & Moisture in Buildings." Good disagreements on their parts on what and how, but they both agreed that the metrics currently available and in use are inadequate. If the presentation isn't up, I can try to put my notes into some kind of presentable shape.

Response to Dan Kolbert

Dan,

I found the link: Should Building Codes Regulate Humidity and Moisture in Buildings?

Some quotes from Lew Harriman and Bill Rose's presentation

Here are some quotes.

Bill Rose: "Perceptions of dampness have been shown to be associated with increased risks to public health and safety. [But] Quantified dampness has not been shown to increase risks to public health and safety."

Bill Rose: "What prompted the initial incursions of regulation (building codes) into moisture control? How successful has that been? (I would argue not successful. Moisture control is as contentious now as it has ever been.)"

Bill Rose: "What is the three-way link between dampness, health and ventilation?" [Editor's note: Bill does not answer the question, at least not in the presentation slides.]

Lew Harriman: "We don’t know the dose-response relationship between moisture, mold, microbial growth and health, BUT...we DO KNOW that damp buildings are not healthy. So I don’t think continuing to ignore the issue in codes (because it’s difficult and problematic) serves the public interest."

Ventilation is not about supplying anything

Great blog. A few comments:

• Correction: Acrolein is generated by combustion of almost any carbon-based fuel—cooking, candles, etc. It is not just a tobacco issue.

• Correction: The total ventilation in 62.2 is 3 cfm/100 sq.ft. plus 7.5 cfm/p not 1 cfm/100 sq. ft. In the 2010 version there was a built-in infiltration credit of 2 cfm/100 sq. ft. to get the number you quoted for mechanical systems. In the current version, however, that default infiltration credit is gone. You can, however, get an infiltration credit based on a blower-door measurement.

• Joe and I agree on almost as many things as we disagree on… it’s just that the disagreements are more entertaining for other people.

• Joe and I agree that ventilation is an important factor in getting IAQ, but not the only one. Clearly the emission rate of contaminants of concern are also important. We need to improve the science of all of this and not just do correlations with ventilation rates and say we learned something.

• Ventilation is not about supplying fresh air — it is not about supplying anything. The only things people “use up” in air is the oxygen and something like 2% of the 62.2 ventilation rate would be enough to supply that. Ventilation is principally about removing indoor-generated contaminants of concern. The more you can capture them at their source and the less you can distribute them to the occupants, the better it is.

• Current ventilation standards are set based on engineering judgment by a room full of “experts”, but some of us would like to see that transition to be based on a bit more causality and science. That is the direction my research has gone in the last few years. You might be interested in a recent interview I did: Moving Toward a Health-Based Ventilation Standard.

Response to Max Sherman

Max,

Thanks very much for your comments. I have made your suggested corrections; I appreciate the information very much.

And thanks for the link to the interview, "Moving Toward a Health-Based Ventilation Standard." It's a valuable document.

Health correlations, houses, specificity

As Kevin mentioned, it is very hard to do good research on health outcomes of people living their everyday lives. There are too many variables. Drawing good statistical conclusions on the impact of residential indoor air quality on an aspect of health requires tracking continuously the indoor air quality of many different homes, along with tracking all the other things the residents do outside their homes, and what kind of air they are exposed to. Giant sample sizes are needed. Data collection and correlation of all those factors is overwhelming.

Martin points out that we have data on the health impact of smoking, or of lack of exercise. Indeed, we have data on various single variable questions. I bet we don't have data on the impact of the residential ventilation rates on smoking's health hazards. Adding additional variables increases the cost of good research exponentially.

In the absence of comprehensive data to answer complex questions on indoor air quality, we can either give up, or look for other ways to make useful choices. I like Don Fugler's answer. We know a good bit from laboratory and other tests about the health risks to mammals of breathing a number of chemicals, including several common indoor air pollutants. While we don't have data proving that breathing a varied mixture of these pollutants in a home is also unhealthy, that's the way that I'm going to bet. Minimizing the introduction or production of these pollutants within the home, and ventilating to reduce those that are found to be in present in a given house, seems like a prudent strategy.

It is encouraging that both Don's study of Canadian and other research, and Martin's reference to the 24-year old ASHRAE 62-1989 proposal, suggest a minimum of 0.3 air changes per hour.

0.3 ACPH

Just a qualification on this number: while a number of research projects show that a house air change rate of 0.3 is reasonable at keeping high levels of indoor pollutants at bay, this is for typical houses with typical occupation. A 7000 square foot house with a single resident probably needs no mechanical ventilation other than a bathroom fan. A small house with an active family of six might require 1 ACPH of continuous mechanical ventilation. Houses with high pollutant sources will need higher ventilation rates (or source reduction).

Response to Derek Roff

Derek,

Thanks for your comments; I agree with most of what you have written.

You wrote, "Martin points out that we have data on the health impact of smoking, or of lack of exercise. Indeed, we have data on various single variable questions. I bet we don't have data on the impact of the residential ventilation rates on smoking's health hazards. Adding additional variables increases the cost of good research exponentially."

I understand your point, but I'm not suggesting that we complicate the research by introducing two variables. (We do have data on the health effects of two variables, by the way -- exposure to asbestos and smoking spring to mind.) Let's stick with a single variable -- the ventilation rate provided by installed ventilation fans -- and see what we come up with. We have large longitudinal studies -- the most well-known is the Framingham study -- that look at variables like this. The research is expensive but not particularly complicated.

Preliminary attempts to look at a correlation between residential ventilation rates and occupant health have not yet come up with a strong correlation.

You wrote, "I like Don Fugler's answer." Don Fugler's suggestion -- "0.3 ACPH ... seems like a reasonable goal until we get the expensive health research completed" -- is very similar to the suggestion I made: "it’s wise for builders to install equipment that allows occupants to ventilate their homes at the rate recommended by ASHRAE 62.2."

Second response to Don Fugler

Don,

Thanks for your comment on the need to use common sense when deciding on a ventilation rate. I agree with you completely -- some homes should probably be ventilated at a rate that is less than 0.3 ach, while others should probably be ventilated at a higher rate.

Once again, we're back to the usual answer to so many questions we face: "It depends."

Air change

Surely it is illogical to base ventilation on the volume of a building.

Logic says if a person is breathing 7 litres of air a minute, lets replace 7 litres a minute.

If there are more people, then provide more air.

What are people doing in their homes? Usually sitting, occasionally doing household chores.

These activities use about 7 litres of air a minute.We should multiply this by the number of people

in the home at the time.

A minimal amount of air change at minimal cost.

If pollution or high humidity is introduced then

open a window.

Air changes

I have played with our air exchanger, using a highly scientific approach. I reduced the air changes until my wife complained, then went a little above that level. She has athsma and needs fresh air to be comfortable. According to the ratings of our HRV we are replacing the air at .2 ACH in normal conditions and raise that to .8 ACH during a family dinner/gathering. Seems to work well for us.

actually, Roger, you are poking a bit of fun at yourself by tongue-in-cheek lauding your "highly scientific approach", however, I believe you are dead on! At least YOUR approach uses some sort of direct empirical response(real data) and your control knob is diluting the symptom-causing variable. It appears that one of the big experts, Max Sherman, believes using health symptoms and responses to direct remedial action is the way of the future-- not using theoretical extrapolations as in the past.

This is a great article that truly elicits the main problem with applying IAQ theories to residential home building requirements. Thank you Martin.

I don't enough about it, but it seems to me that leaving the bar for increasing ventilation rates at the point symptoms become apparent might not be the best idea. Isn't that sort of like eating any food you want unless it makes you feel sick?

Plants and IAQ

While not specifically related to ventilation, this talk on improving IAQ might be of interest: http://www.ted.com/talks/kamal_meattle_on_how_to_grow_your_own_fresh_air.html

Mike.

HEPA Filters

Max Sherman's paper indicates that yes, it would be very beneficial to recirculate the indoor air through a filter to remove P(2.5) particulates. Those particulates are apparently the worst of all the indoor pollutants.

You can remove them without fresh air and its resultant energy penalty.

Another house-caused source of respiratory health problems is Legionella. If the hot water tank is kept at, say, 105F and used for showers, it could cause bacterial pneumonia. European codes already address the problem. Ventilation wouldn't help on that one.

Response to Mike Nelson Pedde

Mike,

Kamal Meattle's suggestions make sense in New Delhi, where he can hire low-wage custodial help to hand-wipe the leaves of the plants he installs in office buildings. His program is unlikely to be adopted by busy American families. He suggests installing three species of plants in your home. One of them is the areca palm.

He says, "Areca palm is a plant which removes CO2 and converts it into oxygen. You need 4 shoulder-high plants per person, and in terms of plant care, you need to wipe the leaves every day in Delhi, and perhaps once a week in cleaner air cities. We need to grow them in vermi-manure which is sterile, or hydroponics. And take them outdoors every 3 to 4 months."

OK, that makes sense. If there are four people in my family, I need 16 shoulder-high plants in my living room. And every day, when I come home from work, I will wipe all of the leaves (because I don't have a maid who works for a few rupees a day). And how am I going to put them outside in Vermont in December and January?

Oh, I forgot to list the other requirements -- you need room for lots more plants in your bedroom and the other rooms of your house as well...

Mechanically Tightened Shell + Fresh Air Intake

Martin, and everyone posting to this website, I find all of your discussions both enlightening and a bit overwhelming. I feel that I'm learning so much, but also that I have so much to learn. I would like to solicit some opinions if possible.

My wife and I are designing and building a new home in the Texas Hill Country (west of Austin). I was discussing HVAC / Insulation / Air Exchanges with them and they are suggesting a "Mechanically Tightened Shell with Fresh Air Intake." This seems to consist of construction cement, or some adhesive, added to the stud face, bottom plate, and top plate along exterior sheathing and drywall joints. No mention of outlets. As for the Air Intake, I am assuming it to associated with the HVAC system.

The price is $4,500 for a ~3,000 sf house [3 bedrooms, 1 office (only room upstairs), 2 1/2 baths - propane fireplace - standing seam metal roof - rock exterior ~5" thick, long southern porch for shade].

I had really wanted to go with foam, but it appears this is not going to be possible and they are proposing blown in insulation. I would really like to hear any comments you might have on this approach.

Thank you in advance,

Steve

Response to Steven L

Steven,

If you care about airtightness -- and you should -- the best way to verify the airtightness of your home's envelope is with a blower door. I hope that your builder performs a blower-door test on your house. Ideally, you should have a specification that includes an airtightness goal. (However, it may be too late for that in the case of your current project.)

Here is more information on blower door testing: Blower Door Basics.

I'm not sure what your builder means by "construction cement, or some adhesive, added to the stud face, bottom plate, and top plate along exterior sheathing and drywall joints" -- but I'm guessing that this is a reference to either Owens Corning EnergyComplete and Knauf EcoSeal. For more information on these products, see Air Sealing With Sprayable Caulk.

The reference to an "air intake" may refer to a central-fan-integrated supply ventilation system, but there is no way of knowing what the builder has in mind unless you ask. For more information on central-fan-integrated supply ventilation systems, see Designing a Good Ventilation System.

Response to Martin Holladay Re: Mechanically Tightened Shell...

Martin - Thank you so much for the quick response, as we are driving down to meet with the builder on Monday. The information that you provided and pointed to will be of great assistance at that meeting. I am reading, digesting, and taking notes now.

FYI... we have changed builders mid-stream (long story) and I am now having to adapt to and understand how the the new guy thinks.

The original design called for the attic to be within the conditioned space because we were using foam - allowing smaller than normal A/C equipment (two stage) and providing nice attic storage. We also want to use can lights so this was a good solution.

As I mentioned in the earlier post we seem to be switching to blown-in insulation, but I would like to continue using two stage A/C and can lights. But, from what I read here without keeping the attic within the conditioned space this is problematic without sealing the cans with drywall top-hats (or Seal-a-Lights which don't seem air-tight) and increasing the A/C size. Can I economically keep the attic in the conditioned space without foam? Is there a trade-off or solution that someone here can suggest?

Thanks Again,

Steve

objective of better air quality

When I first read "Musings of an Energy Nerd" I was rather put off by the underlying message of the article but I must say I am rather impressed by all the informed responses it generated. Allow me to explain my initial negative reaction because I think Martin Holladay needs to reconsider some of his comments.I am an architect who has been practicing for 50 years with an emphasis on building inspections. Doing building inspections gives you the chance to see trends as they develop in buildings without having to wait for definitive research which summarizes so many of the responses this article has generated. Those of us who experienced the altruism of the 60's , the Energy Crisis of 1973 and all the Building Code changes that followed to conserve enegy in buildings hopefully learned something that is not so evident even with all the information now available over the internet. Martin's article is full of interesting anecdotes but an argument can be made today for most any hypothesis given the facility of references from the internet. A good building design should have multiple objectives. I contend that the objective of conserving energy is no more important than the objective of creating a healthy environment and in that regard, the first seems to be progressing at the expense of the second and that is not a good thing. Many of the derogatory remarks at the start of the article are typical. I still believe that homes with plenty of fresh air are inherantly heathier than homes that are stuffy and do not have adequate air changes. It is still valid today and more necessary than ever. The connection between ventilation and human health was championed in sanitoriums [rather than by 'sanitarians' as Martin suggests]. Mentally ill people were housed in asylums whose original definition was a place of sanctuary. Now a-days it is estimated that three-fourths of mentally ill Americans are in jails or pententiaries.Canadian Medicare as articulated in the 1984 Canada Health Act had wonderfull objectives which Canadiand can all be proud of--part of our heritage. When the National Buildig Code was changed in 1995 in response to the fact [as explained in the annex of that year] that interior air pollution was seriously defective, we could no longer rely on natural ventilation [opening windows] to achieve a healty environment, and that air changes [fresh air/oxygen] had to be delivered to each and every inhabited room[at a rate similar to ASHRAE's standard ...one complete air change in about 3 hours--it was a wonderful accomplishment. Here we are in 2013 and it isn't happening. Martin muses as to its importance. All these responses from academics and scientists waiting for definitive research to be done on the subject Many are still suggesting opening windows. The uri-formaldehyde trial was the longest running civil case in Canadian history and ended with an indecisive judgement because not enough difinitive research had been done correlating it to health issues. Try doing some building inspections in urban areas not out in the Vermont countryside [installing solar panels to conserve energy] to get a better sense of how compelling the problem of air quality has become.In Montreal,for example, we have nurseries and primary schools that are so unhealty [bad air quality, mould infestationsd] that many have been boarded up and supposedly they are to be demolished and rebuilt. Most of that has to do with the lack of maintenance and poor initial mechanical designs.There is hardly any mechanical code enforcement even in new construction [especially renovations of older buidings] in regard to vital mechanical aspects such as providing fresh air /oxygen and sufficient air changes. I met one builder/contractor at an inspection who told me of renovating 70 older homes in the fashionable Plateau Mt-Royal area and all of them depended on opening windows for "natural ventillation". The other day I inspected a luxurios condominium in Vieux Montreal selling for 1.5 million having gone through a $350,000 renovation yet the mechanical didn't work [made a lot of noise but it did not involve fresh air or air changes]. It faced due south and the vendor said he preferred opening windows. That's a crock. Do building inspections and you will see how no one opens a window when it is too cold, rainy or too hot and humid outside. That's why the building code was changed in the first place. When you get CO2 readings over 1000 ppm and climbing and outside it is 350ppm, you know that can't be healthy. Meanwhile I got carbon monoxide readings in the common areas including the swimming pool , the gym/work-out centre and the garage.We shouln't be waiting for more research, more proof [like the global warming issue or climate change]. You just have to use common sense and observe. To this day, the first thing checked when you go to the hospital is the oxygen content of your blood. It is done for a purpose.

Response to Morris Charney

Morris,

This article does not question the need for mechanical ventilation in homes. It is about ventilation rates, not about whether ventilation is necessary.

I have championed the need for residential ventilation for many years. This article includes a link to my 2009 article, Designing a Good Ventilation System, in which I wrote, "Homes without ventilation systems are homes of the past. The building science community has reached a consensus: build tight and ventilate right." In the article on this page, I once again emphasize this important point: "It’s wise for builders to install equipment that allows occupants to ventilate their homes at the rate recommended by ASHRAE 62.2."

This article looks at the existing scientific evidence linking residential ventilation rates with human health. It's hard to go forward to make recommendations to builders and homeowners if we don't first start with an examination of the scientific evidence.

You wrote, "An argument can be made today for most any hypothesis given the facility of references from the internet." That may be true, but in my research I didn't rely on just any old references on random web pages. I relied on interviews with Max Sherman, a senior researcher at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, a nationally recognized expert on residential ventilation who has performed years of research on the topic and who is the former chair of the committee that developed the ASHRAE 62.2 standard. (I have been interviewing Max Sherman on this topic for at least 12 years, since I was editor of Energy Design Update. By the way, I happen to feel a certain kinship with Max, since he has received an ASHRAE award named after my grandparents: the Louise and Bill Holladay Distinguished Fellow Award.)

I also relied on the best published research I could find on the topic, and on interviews with Joe Lstiburek, another former member of the committee that developed the ASHRAE 62.2 standard.

You wrote, "The connection between ventilation and human health was championed in sanitoriums [rather than by 'sanitarians' as Martin suggests]." I know the difference between a sanitorium and a sanitarian, Morris. A sanatorium is a type of health facility, while a sanitarian is a public health expert. The term "sanitarian" was in use over a hundred years ago, when public health issues in urban tenements and "miasma" fears were national concerns; the term is still in use today.

You wrote, "When the National Building Code was changed in 1995 in response to the fact [as explained in the annex of that year] that interior air pollution was seriously defective, we could no longer rely on natural ventilation [opening windows] to achieve a healthy environment, and that air changes [fresh air/oxygen] had to be delivered to each and every inhabited room[at a rate similar to ASHRAE's standard ...one complete air change in about 3 hours--it was a wonderful accomplishment." I agree, and nothing in my article disputes the wonderfulness of that accomplishment.

You wrote, "Try doing some building inspections in urban areas not out in the Vermont countryside [installing solar panels to conserve energy] to get a better sense of how compelling the problem of air quality has become." In fact, for seven years in the 1990s, I worked as an inspector doing capital needs assessments for low-income housing projects, many of which were located in Burlington, Vermont -- not that far from Montreal. I visited countless occupied homes and apartments. I have seen it all: moldy bathrooms, dripping windows, plumbing leaks under kitchen sinks, wet crawl spaces, and attics filled with mold. I have seen non-functional HRVs, disabled bath fans, and confused occupants.

Like you, I have a strong desire to make good recommendations to designers, builders and homeowners facing this type of problem. That takes a whole-house approach based on building science. We can't address these issues without a foundation in scientific knowledge based on data. This article is an attempt to look at the existing data so that we can all go forward with sound recommendations.

I must say your answer to my

I must say your answer to my comments is very different from what I understood of your "musings of an energy nerd". If it was meant to be about ventilation rates and not about the need to ventilate [mechanically] then why is it that so many follow up responses seemed to be questioning the need for mechanical ventilation and alluding to the benefits of opening windows [natural ventilation]? My point was that mechanical ventilation requirements as expressed in the 1995 code are not being followed and are being reduced significantly by those promoting conservation of energy. Manufacturers have come up with air exchangers/heat recovery ventilators which don't work. They are not operated continuously, they pollute too easily because filters are too rudimentary, the air volumes are too restrictive, incapable of achieving a complete air change within 3 or 4 hours and most use flexible ducts which can't be cleaned. The preoccupation with outside pollutants [fresh air being the source of the oxygen that is needed] is also a non-issue if one uses a filter of Merv 11 quality [4 inch, pleated ,disposable]. Noone seems to be willing to promote good air quality [as prescribed in the code] with the excuse that it can only be accomplished at the expense of energy conservation objectives. Why would the rate even be an issue [which you say was the essence of your article] when variable speed controlls are available for mechanical equipment. Most AE/HRV units currently in use are being operated with humidistats [which makes no sense]. HVAC systems, AE/HRV's and their controls are needlessly complicated. When the air changes are adequate in a home, you are able to smell the fresh air, you know that it is working. Why suggest that we can't address questions [such as the rate of mechanical air changes] "without a foundation in scientific knowledge based on data". The judgement that came out of the urea-formaldehyde case was to the effect that the degrees of sensitivity varied by individual and you can't make generalized correlations between contaminants and individual health based on absolute numbers. That is why we do not have fixed standards for mould spores, bacteria or most other airborn microscopic contaminants for indoor air. Indoor air is compared to outside air [supposed to be better]. We are finally starting to accept that HES people all have different levels of sensitivity to electromagnetic fields. It would be similar in regard to airborne contaminants. I am suggesting that the rate is not an issue if you provide an HVAC system including a fresh air intake with a variable speed. It isn't happening because homeowners [when they have a choice] are being told it would cost too much...to conserve energy.

Response to Morris Charney

Morris,

I suspect that you and I are in agreement about many issues relating to residential ventilation. I think you are reacting to guesses concerning what I have written rather than to the words I wrote. I urge you to read carefully what I have actually written.

You sound frustrated that many residential ventilation systems are poorly designed, poorly installed, and operated incorrectly. These issues frustrate me as well, which is why I wrote, "Several research studies have shown that a high number of mechanical ventilation systems are poorly designed or installed. Among the common problems: Ventilation fans with low airflow because of ducts that are undersized, crimped, convoluted, or excessively long."

You wrote, "If it was meant to be about ventilation rates and not about the need to ventilate [mechanically] then why is it that so many follow up responses seemed to be questioning the need for mechanical ventilation?" Well, Morris, I'm not sure -- but this website is a lively forum that attracts opinionated readers who like to debate, and the give-and-take by readers often results in a spirited dialogue. I can hardly be faulted for the opinions of people who post comments on these pages.

You wrote, "My point was that mechanical ventilation requirements as expressed in the 1995 code are not being followed." The problem of code compliance is not restricted to Canada. We also have a huge code compliance problem in the U.S. The issue is complicated, but I am on your side on the issue of code compliance, which I address frequently on these pages. For example, I have written, "Several studies have documented the fact that in many areas of the country, energy code provisions [are] largely unenforced. ... To this day, most Vermont jurisdictions have no building inspectors. In essence, the Vermont energy code is entirely voluntary. ... The trouble with uneven enforcement, however — in addition to the obvious point that energy waste contributes to global climate change — is that a builder can never be sure when a new building official will begin enforcing long-ignored regulations."

You are frustrated that many homeowners have ventilation systems that "are not operated continuously." This will be a tough problem to solve. I'm not exactly sure how you are going to enforce regulations requiring homeowners to operate their ventilation equipment according to your preferences rather than the homeowners' preferences. I think the best we can hope for is that -- at a minimum -- builders install equipment capable of ventilating at the rate recommended by ASHRAE 62.2.

You wrote, "HVAC systems, AE/HRV's and their controls are needlessly complicated." I share your frustration with overly complicated HVAC equipment, which is why I wrote (In Simplicity versus Complexity), "Many of today’s harried homeowners don’t even know where all of their mechanical equipment is located, much less the equipments’ maintenance requirements. ... When specifying equipment, keep it simple."

You ask, "Why suggest that we can't address questions [such as the rate of mechanical air changes] without a foundation in scientific knowledge based on data?" My conclusion in this article is the same as yours: although we lack enough data to pin down a correlation between ventilation rates and health, we nevertheless should provide and use mechanical ventilation systems. Even though there are gaps in our knowledge, and even though research is spotty, we need to go forward with the best information we have. That said, it's always a good idea to look at the data we have.

I certainly agree with another one of your points: "The judgment that came out of the urea-formaldehyde case was to the effect that the degrees of sensitivity varied by individual and you can't make generalized correlations between contaminants and individual health based on absolute numbers." That's one of the obvious conclusions of the article on this page; that when it comes to making recommendations on the ideal ventilation rate for homes, the best answer is often, "It depends."

In short, Morris, you have set up a straw man and argued strongly against him. I am not that man.

A blog by Matt Risinger

A recent blog by Matt Risinger (posted on the Fine Homebuilding website) picks up some of the same themes discussed here.

Thanks for a Great Post on Ventilation

As usual, you do your literature research and present a large amount of information in a small space very efficiently. You are a terrific writer too. Keep up the good work!

Log in or become a member to post a comment.

Sign up Log in