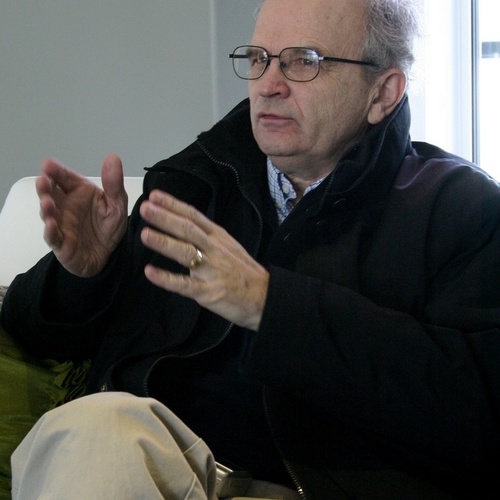

Image Credit: Energy Vanguard

Last week I got a chance to sit down and talk with Terry Brennan in Dallas at the Air Barrier Association of America’s annual conference. He may not be as famous as Joe Lstiburek, but he’s every bit the building science pioneer. Armed with a physics degree, the ASHRAE Handbook of Fundamentals, and a desire to reduce the environmental impact of buildings, he built houses and wrote energy modeling computer programs back in the 1970s and ‘80s.

When he finally met Lstiburek in the early ‘80s, he learned not to bet against Joe’s ability to do ridiculous things. Read the transcript of our conversation and find out what that bet was and more.

The interview

Allison: How and when did you get into building science? Your background is physics, right?

Terry: Yeah, I trained in physics at Northeastern in Boston back in the late 1960s.

Allison: Undergrad degree? Graduate degrees?

Terry: Undergrad. In 1977, I had gotten real interested in ecology and, of course, there weren’t any real graduate degrees in environmental science so I got a job as an interpretive naturalist at a wildlife sanctuary. I did that for several years and then both University of Michigan and Antioch offered master’s degrees in environmental science, so I went to Antioch and got a master’s degree.

Allison: How did you go from there to buildings?

Terry: Well, because of the oil embargoes in the ’70s, I had gotten real interested in the amount of energy buildings use and the impact of that energy use on the environment. We knew about it back then in the environmental field. So I got interested in buildings via sustainability. I came at it from the impact on ecological systems that I was seeing from energy production and how can we reduce that. That was the path I came through and that was while I was working as a naturalist. I had already acquired an old ASHRAE handbook while I was working as a naturalist. We had built a nature center at the sanctuary and…

Allison: Was that the Handbook of Fundamentals?

Terry: Yeah, Handbook of Fundamentals. So with the training in physics it was pretty easy for me to figure that stuff out. I grew up in construction. My first job was with my uncle as a mason’s tender.

Allison: Mason’s tender? Is that like a hod carrier?

Terry: There’s a lot of lifting and carrying. A lot of what I did was mixing mortar and carrying mortar to the mason’s and striking joints, which is where I learned that if they’re not going to see it, don’t bother to strike the joints.

Allison: That was when you were a teenager?

Terry: Yeah, I was 13. We did a lot of concrete flatwork and a lot of 4-ply, built-up hot mop roofs.

Allison: That was in the Northeast somewhere?

Terry: Yeah, I was up in New York near where I live now. So with those skills I worked my way through physics training as a carpenter, so I had a construction background and I had the science training. I had realized that the chances of being able to contribute something significant in physics were pretty remote. I would have had to somehow gotten access to a synchrotron…

Allison: There is one in New York.

Terry: There is! Brookhaven National Lab, and I actually was there for a couple of months when one of my physics professors was testing out theories he had waited his entire career to test. This was one of those transitional events for me. He had spent his entire career developing some hypotheses about some subatomic particles. He had two months to demonstrate his theories and nothing panned out. There was a big argument between the theoreticians and the experimentalists, and I thought, I don’t want to do that. I don’t want to bust my ass developing theories or learning to be a good experimentalist in order to go through what these guys just went through.

When I have free time, I get myself up into the mountains and go camping and climbing. In graduate school, I worked on independent studies because I was real interested in buildings. I worked on independent studies with Bruce Anderson’s total environmental action principle, which at that time was doing lots of solar energy and energy conservation in the design of buildings. They had lots of money to do that.

Allison: Who was that?

Terry: Bruce Anderson. They published Solar Age magazine, which eventually turned into Progressive Builder and then eventually went out of business. I had a great time. I did practicals at a community land trust in Vermont. They designed a number of houses, grain dryers, and they have solar hot water heaters, heavy insulation, solar-dried composting outhouses. I… did classwork in forest ecology and fieldwork in forest ecology, a lot of work on environmental economics.

Allison: Environmental economics?

Terry: Yeah, how to think about our economic systems. At that time, the report from the Club of Rome had just been published.

Allison: Limits to Growth?

Terry: Yeah, Limits to Growth had just been published so we were reading the limits to social growth and Herman Daly’s steady state economic theories.

Allison: How long has Camroden Associates been around? Is that your company?

Terry: Yeah, that’s my company that I started in 1982 after graduating and returning to central New York and helping to develop a two-year solar energy program at Oneida County Community College. The part of that that I actually taught was the building enclosures and mechanical systems, and other folks were already teaching about solar thermal collectors and photovoltaics. I was helping people to design and build low-energy use houses. We did that. We built houses and we were sealing them to between 1 and 2 air changes per hour…

Allison: Camroden Associates built houses?

Terry: Yeah.

Allison: Do you still do that?

Terry: No. You know that’s what I was doing essentially to bring in the money. I was teaching at the community college and designing and building additions and houses in central New York with a small markup. We weren’t doing many projects a year.

It turned out, yup, we could make them airtight, we could insulate them heavily and deal with the thermal bridges, so I got to think about all this stuff. So I wrote some thermal network programs so I could model things that we couldn’t model just using what’s in the [ASHRAE] Handbook. I did that first on a TI-59 programmable calculator and then I wrote…

Allison: You didn’t have an HP?

Terry: The RPN [Reverse Polish Notation] HP, I did have an HP, but I didn’t have one powerful enough that I could program it to do what I could with the TI-59. I wrote a program to do Glaser analysis on assemblies to look at dew point conditions within the assemblies.

Allison: So when you were building and working on houses back then, this was the heyday of solar homes and superinsulated homes, did you fall on one side or the other? Superinsulation or passive solar? Or you did both?

Terry: Well, I did a cost-benefit analysis on incremental changes in the insulation… the level of insulation in the walls and the foundation and the roof assembly, and I used the solar radiation models that Beckman developed for solar collectors, and I used that to calculate how much sun would land on a window anywhere in the house. I calculated what model… would transmit, absorb, and re-radiate and reflect, solar… and all that.

When I would set up a program to do those calculations and change the levels of insulation and go through a whole list of possible improvements and calculate the cost-benefit for each improvement, do them all and then select the one with the best cost-benefit ratio, I’d put that in the model and then do all the calculations all over again, and it would print out a prioritized list that would then allow us to go into a house… and where I ended up the houses I was building were about an R-24 to R-28 wall, sealed up to…

Allison: This was in upstate New York.

Terry: Yeah. Upstate New York, a seven to eight thousand heating degree day climate. All the walls I came up with, I did something to get rid of the thermal bridging… Insulated the foundations to about R-12 with foamboard on the exterior…

Allison: Did you do under the slab or just the perimeter?

Terry: It depends on how far down we actually went. I did a fair number of energy audits in the early 1980s and what I discovered was that my computer model, for how much energy they should use, way overpredicted the amount they actually used and when I looked at what might cause that, I came up with, the basement walls, what they tell you in the ASHRAE Handbook for basement walls was way too high. And I calculated too big a heat loss for infiltration, so I did a 2-D model of heat loss in basements and developed a table that I could use for doing that — what ASHRAE came out with a few years later.

Allison: Were you a member of ASHRAE by then?

Terry: No, I didn’t join ASHRAE until about 2000, so I had done that, and then [some researchers] in Canada came out with a method for basement walls that came up with a lot… that I came up with, so that helped a lot. And then I thought about why the infiltration calculation would be so wonky, so I…

Allison: Were you aware of Larry Palmiter and those people? Was Larry working on infiltration at that time? I know Max Sherman was.

Terry: Yeah, I think he was. Max Sherman I knew about because I knew him personally — because I had met him in I think ’81. He had just finished his PhD at Princeton, and I had gotten his thesis and talked to him a number of times. I knew about Max’s and Grimsrud’s model so I was looking at their model, and I was using their model in my program and did a bunch of tracer [gas] measurements…

Allison: So you wrote a program to do the energy modeling for a whole home including infiltration and all that?

Terry: Oh, yeah. Once microcomputers came out, I got a microcomputer in 1979.

Allison: What language did you write it in?

Terry: I wrote it in BASIC, and I wrote two programs. I wrote one that was an hourly thermal network simulation in which I could model almost anything I wanted to, but it would take me three days to set it up and then I’d start it running and… it would take all night for it to run.

Given that, what I did is I made a modified heating degree day model. I divided the day up into daytime, nighttime, and dusk and dawn time periods and calculated separate heating degree days based on what I extracted from the hourly data and TMY data, and divided each month up into cloudy days and sunny days and then divided the cloudy days and sunny days up into those time periods for the day and calculated heating degree days from that.

So if I had a typical sunny day and a typical cloudy day and I just weighted them by the number of them so I could do two simulations that were not hourly where you had four calculations for the day or two calculations for the day. Then I could do much simpler calculations without simultaneous equations and numerical solutions, and then I just did the ordinary heat load calculations and applied that. I used [someone’s?] calculation from LBL for the window components. That gave me really good results except infiltration… Then I check through all those options and then print out the cost-benefit ratios. It made life much simpler.

Allison: There must have been quite a lot of time put into developing that.

Terry: Oh, yeah!

Allison: I can see you typing line after line of code

Terry: Yeah, and debugging it and making sure that it was actually the calculating the parameters I wanted…

Allison: Did you store the programs on cassette tapes?

Terry: It was initially on cassette tapes and then on floppy disks and then eventually on hard drives. It got to the point where I couldn’t run them anymore because all the operating systems had changed and there were other models available that were pretty good. By that point I was drawn from… Well, for a while I was the basement guy and for a while I was the window guy, and by then, buildings were so tight I started seeing moisture problems, high humidity problems, and started working on indoor air quality.

But I did figure out what the infiltration issue was… So I modified the calculations for that, and then I thought, well, the air coming in through the cracks in the walls [?] so I measured it. I made my own collection boxes and I put them on the electrical outlets and I measured the temperature of the air coming out of the electrical outlets and it’s basically [something?]. So it’s the cracks and air leaks in walls where heat’s being sucked in, so there’s a little heat recovery ventilation. So once I accounted for those things. Suddenly the model’s predicting…

We had a panel discussion about that one time at Affordable Comfort. Gary Nelson was on it and I was on it. I think Mike Blasnik was on it, and maybe Joe, maybe Joe Lstiburek…

Allison: When did you meet Joe? He was doing a lot of work with infiltration back then, too.

Terry: Oh, yeah. Joe and I met back in the early ‘80s. We’d been hearing about each other from people who knew both of us…

Allison: He was also building houses and doing the airtight drywall approach and…

Terry: Yeah, that’s right. People were coming up to me and saying, “You’ve got to see this guy, Joe Lstiburek. He’s doing the same kinds of things you’re doing.” We eventually met and hit it off right away. I think it’s probably because of two things: One is that the New York state energy office wanted to have him come and give a talk, but they were afraid, so they said, “We want you to introduce him and moderate him.” I said OK.

His plane was delayed and he got there about 20 minutes late. There were all these people there to listen to him, and I said, “Well, I’m not Joe Lstiburek, but I can tell you he’s going to make a joke about a spider.” I sort of told them what two or three of his jokes were about, and I had a little Canadian flag up at the podium. And then I said, “And he’s going to tell you about how much dumber Americans are than Canadians.”

Then Joe came in, and I introduced him. He got going, and he was doing the Joe Show. Then he said, “Let me tell you a story about a spider,” and everybody cracked up laughing. So he tells the joke, and then he starts a rant about “you Americans,” and I picked up the Canadian flag and I was waving it around. Everybody’s laughing, and he turned around and said, “What’s going on?” Then he told another one of his jokes and everybody started laughing again, so then he caught on that I had set him up. He just loved it. He loved that someone would break his balls like that.

Then we went out drinking later that night. I lost a bet that he couldn’t stand on his head on the table at the bar and drink beer and sing the national anthem of Canada at the same time. And it turns out he can. I believe we got thrown out of that bar.

At any rate, Joe and I hit it right off, and I think it’s because of a combination of — we looked at these issues and we came to the same conclusion. Now, I’m jealous that the had Timusk and Handegord and those guys to help him, and in the U.S…. I mean, I love Doug Burch and Max and Dave Grimsrud. Most of those guys we had, I’m grateful for them. But we just don’t have the building science tradition that Canada does. So we… Thank God I didn’t go to school to be an architect or a structural engineer, because I was coming to it fresh, with a physics background and a biology background. I could just apply fundamental principles to a problem. I didn’t have the baggage of having been taught to think about it in a certain way. That helped me a lot to figure things out.

Anyway, I guess that’s a long way of telling you how I got interested in this stuff. Then I looked at the ASHRAE Handbook and I realized a bunch of this stuff’s wrong. And the ASTM standards about moisture… We just had no real understanding of how water molecules behaved… And that’s all changed. I never thought it would change. But I’m astonished at the progress.

Allison: What is your biggest concern with buildings right now?

Terry: You mean like building science stuff, not like the entire way we fund buildings is completely criminally insane?

Allison: Well, yeah, it’s hard to avoid going to that issue because that’s where the problems stem from.

Terry: Well, there’s plenty of things that I worry about. I’m worried about a proliferation of standards and codes. Quite a number of the changes have stopped [people from] doing dumb stuff, but when you do a code or a standard, there’s this tightrope you have to walk. How can you write it so it’s protective and stops the really stupid stuff from happening but at the same time doesn’t prohibit people from doing something innovative or in some way better?

The standards in museums have really ratcheted this up a notch. It’s like, we really don’t want [interior conditions] to vary much, just a little bit all year round. You know, there’s real problems with that. First, it’s not necessary to make that tight a control. If you take a masterpiece out of someone’s mansion that hasn’t been held to that and it’s now in an entirely new temperature and moisture regime, it’s going to tear it apart. It’s going to fail.

I’ve done a few museums over the years, so I’m real familiar with this. I helped an archivist at the Smithsonian. They were having problems with the film storage vault, where they stored photographs and movies, and they had an amazing collection. You want to keep it dry and cold to slow up the chemical reactions because it eats itself. So they were trying to keep it at 34 or 35 degrees, and they were getting icicles. They contacted me because they wanted to know how you can accurately measure relative humidity at 35 degrees. Down near freezing temperatures, how do you do that? Because ordinary humidity monitors don’t work. So I told them you need to use chilled mirrors. That’s the only way you’re going to be able to do that. Then they did that and we figured out they had an air leak. So they got the mechanical guys in there and they tore out the whole system, and that’s where the air leaks were — duct leakage. They redid all that and got it under control.

Those kinds of things fascinate me.

Postscript

It was a pleasure getting to sit down and talk with Terry about his building science history. He’s one of my role models, too, because the first time I heard him talk (at EEBA, 2009), I found out that he also experiments on his family; he showed bath fan data from his own home. Also, I spoke with Joe Lstiburek and heard the spider joke and the reason they got kicked out of the bar. Since this article has gotten so long, though, I’ll have to tell those stories another time.

Allison Bailes of Decatur, Georgia, is a speaker, writer, energy consultant, RESNET-certified trainer, and the author of the Energy Vanguard Blog. Check out his in-depth course, Mastering Building Science at Heatspring Learning Institute, and follow him on Twitter at @EnergyVanguard.

Weekly Newsletter

Get building science and energy efficiency advice, plus special offers, in your inbox.

7 Comments

Thanks, Allison

For a couple of decades, at any conference I've attended, I've always sought out the chance to hear a presentation by Terry Brennan. He's rather quiet and unassuming, and he is very smart and very funny. He has an offhand, dry sense of humor, delivered without any particular emphasis or showmanship.

He is a fount of fascinating stories, and knows more about most building science topics that almost anyone. Thanks for a fun interview.

You're welcome!

You're welcome, Martin! I've heard Terry speak several times, and he's always a pleasure to learn from. One of my favorite things that he includes sometimes is what he refers to as "the subliminal part of my presentation." That's what he says as he races through a bunch of slides toward the end of his talk because he's got too many slides for the amount of time remaining.

And yes, he's a wealth of building science knowledge. At the 2011 Summer Camp, Terry, Gary Nelson, and Collin Olson did a full day on blower door testing, and this is what Joe said about the session: "Are you kidding? This is the 'Dream Team.' No one, and I mean no one knows more about air leakage testing of buildings than these folks."

aside on economics

I'd be curious to hear more about this intersection of economics and building science. Anybody know if Terry or anyone else has written on this in detail?

Response to norm farwell

Norm, one of the best explanations of this I've seen is in Stewart Brand's wonderful book, How Buildings Learn. See Chapter 6: Unreal Estate.

Nyserda Joe L. At West Point

Nyserda Joe L. At West Point decades ago.... Is that when you met Joe Terry?

That event changed my outlook on building.

I like the point about stifling innovation via strict codes. I have mentioned it many times that in my area the enforcers enforce the use of poly that GBA says is absolutely wrong.

Builders need full sets of free to use specs to build moisture safe superheated homes. GBA is a start to moisture smarts but mixing and matching GBA knowledge is worse than having no knowledge. Just read some of the Q&A and you'll see what I mean.

So someone start a site with full sets of building specs. That is what is now truly in dire need. We builders love learning but our job is to read plans and build.

Thanks for all you building scientists do for us.

Aj

Response to aj builder

Joe did say it was in West Point. Were you one of the people laughing when Joe began the spider joke?

We were so entertained that

We were so entertained that we had to attend another seminar to try to learn some building science.

Somewhere I have an audio tape of that get together too!

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in