Image Credit: All photos: Ajahn Sona

Image Credit: All photos: Ajahn Sona The main building at the Birken Forest Monastery measures 10,000 square feet. The main building is heated by two wood stoves. Hinged insulating shutters reduce heat loss through the windows at night. Some of the insulating shutters are quite large.

Birken Forest Monastery is a retreat center in the mountains of British Columbia. It’s located at an elevation of 4,000 feet at Latitude 51, and experiences about 9,000 heating degree days (Fahrenheit) per year. The buildings are about 15 years old.

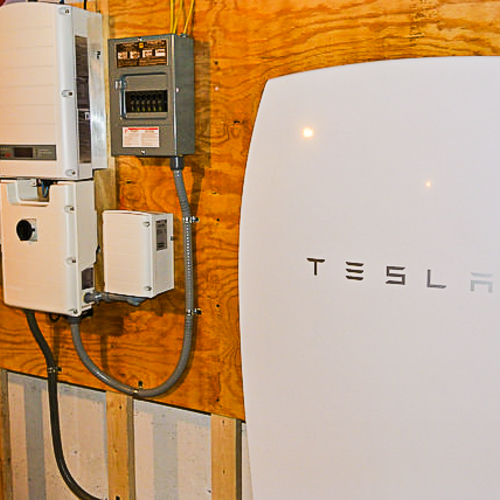

We are off the grid. The nearest electricity line is 4 miles away, and it would cost about $200,000 to bring grid power in. (Then, of course, we would still have to pay for the electricity.) So off-grid it is, and will remain.

Years of off-grid experience

I have lived here for 14 years and have gained much off-grid experience and knowledge by the sometimes harsh teaching methods of Mother Reality. I should mention that I have been a Buddhist monk for the last 28 years. It doesn’t matter much, except that my training is to find simple and sufficient ways of life. How we do things, I believe, is appropriate to a comfortable American lifestyle as well, so I hope you can apply any of these strategies to your own houses, whether off-grid or on.

I won’t go into too much detail about the evolutionary process, but it is important to note that our first set of photovoltaic (PV) panels, rated at 1.8 kW, cost about $10 per watt installed. At that price, the PV system still made sense compared to our 12-kW Kubota liquid-cooled 1,800 rpm diesel generator. (By the way, the Kubota generator about as fuel-efficient as possible for any kind of generator.) We charged a bank of batteries with it, which optimized the engine efficiency even more.

How efficient was the generator, you wonder? About 32%. The energy you capture from a gallon of diesel is about one-third of its potential. Diesel fluctuates in cost; it’s at least $4 per gallon in Canada… sometimes $5. That translates to 50 cents per kWh of electricity, plus the life-cycle cost of the generator — so add maybe 20 cents. So the brutal reality of high-cost electricity (70 cents per kWh) turns you into an inventor/economist/minimalist, overnight.

PV costs are dropping fast

Fast forward in time, through an 80 kWh wet lead-acid battery bank for 7 years, to an 80 kWh maintenance-free AGM lead-acid battery bank for 6 years, to the present: we now have a recently installed 40 kWh AGM maintenance-free Surrette battery bank. Notice that this bank is half the size of the previous two. The cost of our latest battery bank: $8,000; life expectancy, 8 years.

The reason for the smaller battery bank: the PV array went from 1.8 kW to 3.4 kW in 2009, and then in November 2014 to 11.4 kW!

That’s a startling jump in solar power. Why? The economics are these: The additional 8 kW array was installed by an electrical engineer and two journeymen electricians for $3 per watt. There were no subsidies, no tax rebates, no special deals. The only things that weren’t new were the previously installed inverters.

A new age in off-grid living has arrived. Old formulas must be revisited.

Monitoring is essential

I carefully monitor all systems with sophisticated devices such as the Pentametric battery monitor, an hour counter on the diesel generator, a TED 5000 whole-house monitor, and daily notes and observations. December is the worst month, averaging 47 hours of bright sunshine (about 1.5 hours per day).

Now that we have a much bigger PV array, what will happen to our diesel use? In December 2013, when we had a 3.4-kW PV array, the diesel run-time was 60 hours. In December 2014, with our new 11.4-kW PV array, generator run-time was only 10 hours. Hmmm.

We are short about 50 kWh from being 100% off-grid solar. The generator run-times occurred on seven occasions, with each occasion requiring no more than 10 kWh. Conclusion? An additional battery bank rated at 20 kWh would zero out the generator year ’round! Now that may not mean much to you on-grid types, but any off-gridder will know that that is traditionally impossible amongst us forest-dwelling folk.

Think again, my fellow hobbits, think again!

Lowering electrical demand

Now the question: “Is it worth it?” In order to answer that, I have to expand the view to include the rest of the set-up.

Here is a snapshot of the main house. It measures 10,000 square feet. (Yes, you heard that right.) It has 12 bedrooms. It can accommodate 15 people and another 8 can use the facilities (sleeping in 8 separate “tiny houses”). The total population of 24 uses 5 washrooms, showers, cooking, 4 computers, all LED lighting, a 300-foot-deep drilled well, refrigerators, freezers, etc.

Now our average population is 12 to 15 people, but hundreds of people stream through year ’round. Our average electrical demand is only 12 kwh per day!

Yes, there is a deep back story to how we do it. I mean, we are talking about ¾ kWh per day per person, with all modern conveniences, including four-slice toasters, microwaves, dual-flush toilets, 4 showers, pressure pumps, a well pump, two refrigerators, and a freezer. (The refrigerators and freezer together use 1.2 kWh per day. They are in a large “cool room.”)

So without carefully controlling our electrical demand with super-efficient appliances, our 100% off-grid solar community would not be possible.

Not much sun during the winter

Our climate is not good for solar in the winter. Virtually anywhere in the U.S. is at least as good as we are, or better. Certainly the eastern U.S. has similar solar resources. But here’s the thing: for nine months of the year, we will produce about 7 times what we need for our electrical demand! Yikes, what a nice problem to have. (We deserve this problem, we created it!)

So, how much domestic hot water do we use? (You may have guessed that I know exactly how much.) I have installed a water meter on the 95% efficient 200,000 BTU/h propane on-demand water heater that supplies the whole house: 80,000 BTU/day, or 23.5 kWh if we think in terms of an electric plain-Jane water heater tank. Easy: we have up to 50 kWh on many days leftover. Now we could chop that down to 9 kWh by using a heat-pump water heater, but do we need to scrimp? It is an edgy question.

We plan to get an electric vehicle soon to mop up some of that excess electric production, but both together could be supplied rather easily for nine months per year.

Cost-effectiveness analysis

So back to economics. How much propane savings? About $1,000 year.

How much gasoline savings? $2,000.

How much diesel and generator life wear? Maybe $800. Total savings, about $3,700 per year.

The payback period for the off-grid set-up (PV and battery payback) is (drum roll) 10 years. That includes the rather short life of the batteries (8 years) and the rather long life (30 years) of the solar panels.

Superinsulation helps reduce our energy needs

I’ll conclude with a brief description of the enormous house. It is superinsulated, with R-80 ceilings. The walls range from R-60 down to R-20 (on the south wall.) The big innovation is our R-25 polyiso-and-birch-plywood insulating shutters for all our windows. The building has 1,350 square feet of argon-filled low-e dual-pane windows. When it became apparent that the building is over-glazed, we permanently installed insulated R-30 exterior shutters over about 500 square feet of glazing, leaving about 850 square feet of windows exposed. These windows have been fitted with hinged R-25 shutters that open inward. Most are hinged at the top, although some are side hinged.

More than any other feature, these gasket-sealed insulating shutters contribute more to heat retention than any wonder machine or triple-glazed German miracle windows, for far less money… 80% less. (I’d be happy to go into detail if requested). During the 12- to 16-hour night, we basically don’t have any heat loss through our windows. In the daytime, with panels open, there is solar gain. It’s a win-win situation! For eight months of the year, we leave the panels open.

The space heating is supplied by two indoor high-efficiency wood stoves. We burn 5 cords of fir per year, locally collected. (British Columbia is the Saudi Arabia of firewood.) We don’t need any electric fans for air circulation.

Although there is in-floor radiant heat distribution throughout, we do not use it, ever. (Another learning experience). So for space heating, we need about 75 MBTU per year in a 9,000 heating degree day zone. Not bad. It’s not a Passivhaus (that would require 50 MBTU for a house this size), but it doesn’t require a heat-recovery ventilator! We have exhaust-only ventilation using 5 bathroom fans and 2 kitchen fans. Natural air purification also occurs through 70 large houseplants — a method recommended by NASA for air purification (not kidding).

By the way, the kitchen is completely isolated from the main building by a glass door during cooking, so no air contamination spreads throughout the house. (This design detail just might catch on; this type of kitchen isolation was standard in large 19th-century houses.)

All in all, good air, good light, good vibe, good economics. And thank you, Green Building Advisor, for so many good thoughts on building. I have benefited immensely.

A concluding note: Our total energy use from all sources is 35,000 kWh per year. The Passivhaus allowance for a house this size would be 110,000 kWh per year. So we use 70% less energy (total kWh) per year than the Passivhaus allowance. Something to reflect on.

Ajahn Sona was born in Canada. His background as a layperson was in classical guitar performance. He was ordained as a Theravada Buddhist monk at the Bhavana Society in West Virginia. In 1994, he founded the first Birken Forest Monastery near Pemberton, British Columbia. In 2001, Ajahn Sona established Birken in its final location just south of Kamloops, British Columbia. Ajahn Sona posts comments on the GBA web site under the pen name “Ven Sonata.”

Weekly Newsletter

Get building science and energy efficiency advice, plus special offers, in your inbox.

13 Comments

Over glazed?

I would hardly think your building is over glazed. At 10,000 s.f., it seems 1300 s.f. of glazing is not so much. The photo certainly does not scream out that the building has to many windows. In any event, I think the insulated shutters idea is brilliant. Is there a fear of heat build up between a shutter and a window if someone forgets to open an interior mounted shutter on a south facing window in the morning? Or is that not much to be concerned about?

You also said that you do not use your radiant floor heat. You're not to first poster to say that on GBA. I'm wondering if you might expand a bit on what your experience was and say more about the kind of radiant heat you installed.

Reply to Antonio Oliver

1350 sq ft. Is 13.5 % of floor area. That used to be considered an ok ratio. A lot of passive house design would consider that excessive even with triple glaze. We are now at 8.5% which still fills the place with light and views during the day. This is an ongoing experiment in appropriate window sizing so note that we reduce the cathedral ceiling windows by 500 sq ft with exterior R 30 panels which are openable if we ever wanted to. We waited a year and never felt the loss, so they remain sealed but the window are still there if we perhaps want more spring fall solar gain...unfortunately these giant windows face East and so would overheat 4 months per year as the morning sun pours in. They would probably be opened if south facing.

Yes, yes, yes. Interior closing panels will easily crack dual pane windows if left shut with direct sunlight...unless they are tempered. Many of ours are tempered 8 foot sliding doors on the east side. They won't crack but you can get gasket melt. Ordinary single glaze might not crack since it is the difference in temperature between the two panes which seems to cause the inner pane to crack. We have a military like discipline about opening and closing the interior shutters. We do have closing exterior shutters on the 5x10 kitchen window so that can be closed in the afternoon when the western stream of summer sun might overheat in summer. Of course all west facing windows are in no danger of cracking until the afternoon since no direct sunlight hits them until about 1 pm in summer.

Shutters are a venerable tradition that needs renewing. My thought is interior closing shutters are easiest and they are not subject to wheather. They can look better than a jet black night window. If they are light color with a little led downlight they can give beautiful light at night where your window openings are. Secondly, to prevent cracking, a very light fabric exterior blind or panel could be rigged to close at the same time as the interior panel. It doesn't need insulation. It just is a direct light blocker. It can be closed from inside with a winder or push button.

Exterior shutters are marvelously effective, as I mentioned, much better than triple glazed windows. Ours are R 30 but even R 40 present no major expense or difficulties. After all it is just a door which closes over a window, how easy is that!.

You asked about radiant heat. We used it for 11 years, with an outdoor wood boiler. It worked great to give even heat throughout 10,000 sq ft, plus domestic hot water, plus a second 1100sq ft outbuilding. It was the only way that we could imagine heating all this because at first the buildings were only R 20 walls and R 40 ceiling

with no window panels. By the way that required 40 cords of wood per year! We began insulating upgrading and inventing, and the unexpected side effect was that wno longer need the outdoor boiler and the radiant heat. The wood use is now about 5 cords, the house heats evenly without circulation pumps or air ducts at all. So a reduction of 85%, wood, and significant reduction of diesel generator produced electricity for pumps. As wel no going outside to feed the stoves.

Outdoor wood boilers are a whole area for discussion which if anyone is interested I can reply in detail.

Very Interesting

Certainly appreciate the concise yet detailed review of your systems. Curious about the hot water system. Do you currently have an electric water heater (or preheater) for the 9 months when the PV is overproducing? Or do you use the propane water heater exclusively? It was not clear to me as I read through the article.

Reply to rjp

For the last 2 years we have relied exclusively on propane on demand hot water. For the previous 12 years a dual propane hot water tank and second tank with copper coil heat transfer from an outdoor wood boiler. So we will now experiment with a large electric hw heater, which has not been installed. I am observing the new pv system to see if it performs as predicted...so far so good. A complete super insulated in ground 3000 gallon water storage tank is already in and plumbed in to the utility room underground so I may opt to electrically heat that as it can hold about 3 million btu. I can either just preheat water to the propane on demand or use a separate electric tank with a coil to use both low temp preheated storage water and boost it to safe temperature of 125 degrees for small storage. I could also use a simple outdoor split heat pump into the 3000 gallon tank if I want get a c.o.p.of 3-5 through the spring summer fall. Definitely propane will be required at least 2 months per year. The experiment here is almost continuously on progress.

Ajahn

Thanks for the very interesting blog. Given your your circumstances up there, describing your PV system as being oversized does it a disservice. Having excess electrical output when producing it doesn't use any energy, and having a very convincing economic analysis of benefits of installing it in the first place when compared to the alternatives, makes it sound just right. Seeing the excess power production as a problem is like saying "My bees produced too much honey this year".

I agree with you that the

I agree with you that the kitchen Isolation might catch on, in 50-100 years anyway. The driver of that will be domestic robots, not heath or IAQ issues. And yes I fully believe that robots will be cooking for us one day (in a few instances they already are).

Have you done anything to reduce cooking loads? I assume those are mostly load shifted to propane, instead of using electric. If so have you thought about the economics of switching back to electric for part of the year? While that's not feasible for most people, perhaps it is not to onerous for your situation.

Cooking with electricity

Donald, yes I am considering going all electric cooking. We already use electric toasters, microwave, water boilers, induction rice cooker, the only things we don' t cook electric with is stove top and oven. We use propane for that. About 9 months a year all electric cooking would no longer be a problem (it used to be unthinkable for off grid...not anymore). The only question is: induction or plain electric resistance?. If you have plenty of kw, induction may not be meaningful to save 30%. Cooking only uses maybe 3 kwh day and we wouldn't even notice that. The battery is full by 10 am so you might as well find some way to use the 20 kwh that are going to flood in in the next two hours. By the way all our cooking is done by noon, we don't eat in the evening, but we might boil water for tea in the afternoon.

Shutters

Could you give a bit more detail on the Shutters? This is something I am currently considering. What did you use for the gasket and do you have any condensation problems?

Shutter details

Exterior shutters are 2x8 frame with fiberglass batt r 28. 1/2" plywood on the window side painted white. Exterior side, exterior t -111 siding. Careful caulking all round. The interior panels are birch cabinet grade plywood, 1/4" window side, 1/2" room side. Frames are fir 1" x4". Build the frame and attach one side with finish nails and glue. Use 3.3" polyisocyanurate paper sided insulation. Glue whole surface, .then add the other face of plywood with glue and finish nails. It makes a very rigid panel that will not twist and is very light. Now it can close to the window trim. Or inside the window frame but you must build a 1"x1" interior frame for the panel to meet. Both ways will work, it is just aesthetics. We did our first ten with neoprene closed cell gasket with reasonable success ...small amounts of moisture. Then we switched to open cell foam gasket with great success...virtually no condensation.

I have experimanted with north bathroom windows keeping the panel with open cell gasket shut for three months in winter down to 30 below zero. When i open to do a moisture check, there is absolutely zero moisture! That is amazing because there is zero permeance through the panel to the ice cold glass, especially in the moist bathroom atmosphere. This is the second year I have run this test and absolutely zero accumulation of ice or moisture occurs.

We also use standard door gasket, like on regular exterior door frames for exterior panels. They are easier to do since the panel is on the outside the window stays warm and does not accumulate any moisture.

The sliding panels are trickiest. Build them the same as hinged panels. Ours are huge...8'x8'. Use 2x4 framing though. It is difficult to describe our sealing techniques, but here goes: Build an exterior frame of 2x4 around the window. Add 1x6 with the lip overhanging to the interior of the 2x4 frame. The bottom slide surface is laminate flooring and coresponding laminate on the bottom of the panel frame...so you have full sealing on the bottom surface as they meet. The closing vertical side butts to open cell gasket. The trailing side has a 2" rubber strip from a garage door closer. It simply meets with a "half round" vertical wood strip that the panel slides over when being close or opened. The top gasket is flush to the window side and contacts the horizontal surface at the top inch of the horizontal interior top 1" of the panel ( a picture would be better!) sliders are much more difficult to seal, however if you are serious you can do it just like a sliding glass door or sliding window. If I had to do it again i would devise two little clamps that suck the panel in to the gasket when closed and are released before opening. I may yet modify them, however moisture has not been a major problem, but we are mercifully in a dry winter climate zone.

great write-up!

Thanks for this very well written description. If you were starting from scratch today, do you think you would still buy the 1800-rpm generator, or put that money into more panels and batteries?

If i had to do it over

Thanks for the question. Doing it at todays prices , I would shoot for 100% solar pv and battery and no generator. It has never been possible before 2014. This is what all old off grid types will have to get their minds around. It is entirely possible even in less than ideal winter light. What should the generator cost and 20 years of fuel savings be spent on? That is the question.

As a rough formula (presuming, of course that you have elegantly optimized your electrical winter demand) enough pv to provide one days demand in one hour of direct sunlight ( between 10 am and 2 pm). For us, that is 11.4 kwh. For a little family... maybe 6 kwh. Next: storage...2.5 days on a good maintenance free battery bank. That means 40 kwh for us giving us 25 kwh available.

Now here is the new think part.: Only about 15-20 times during the 3 darkest months would you need to run a generator. To replace that dreadful beast here is what I suggest: the cheapest low lifecycle wet lead acid battery bank you can find...about 50 kwh. Prepare to discharge it to 90% 20 times per year! You see something has changed altogether. We only scrape bottom in winter now and only occasionally. A high lifecycle battery is TOO LONG LIVED! Heresy, this is! But the heresy of logic I am afraid. At 20 cycles a year 400 cycles will get you 20 years...it is not necessary or wise to go beyond that. I t should be Wet lead because you only water it once per year and equalize it once per year so maintenennce is not an issue. But how do you charge it? You will frequently have days even in December where two good days in a row occur, your high cycle battery is already full by 11 am! ... now charge the clunker up for its next use.

So this is all different than the old formulas, and I was a devout follower of orthodox off gridism for many years and it worked well at the time... Now re think everything! Ok, what if we can't make juice two days a year? Well scaredy cat get yourself the cheapest throw away gas 2 kw generator on the market for that and be prepared to spend $5 year on gas.

Excellent article! I wish GB

Excellent article! I wish GB would allow you to include photographs and diagrams. I have worked as a Certified Energy Advisor (Ontario) and solar assessor for a number of years until 3 years ago. We tried to advise people on how to improve the efficiency of their house mostly in terms of heat retention. One of the missing links for me was heat loss through windows. At the time I did a lot of research into shutters and blinds available in the market that were sealed and insulated. There was very little available.

I eventually found roll-up quilted/insulated blinds that ran in tracks and sealed themselves against the window frame. I purchased one (at great expense) for my sliding glass doors going to a deck and have been relatively pleased with the performance in both winter and summer.

I believe there is a market for well-built insulated shutters (whether people know it or not). Would you be willing to share your design? I have read your description in one of the comments above, but diagrams would be that much better. I haven't looked recently (currently working in Africa), but if GB hasn't done so, an article focusing on insulated shutters would be a great idea!

Thanks again for your very practical story!

Response to Dave Klassen

Dave,

GBA does allow authors of blogs to include photos. If you look at the thumbnails at the bottom of the article, you can see that author Ajahn Sona has included two photos of his insulating shutters (Image #3 and Image #4).

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in