In October of 2013, the German government approved amendments to its Energie Einsparung Verordnung (EnEV), the federal ordinance that mandates energy efficiency for buildings. The revised EnEV reflects the government’s latest energy policy decisions, and it brings the ordinance into alignment with the most recent European Union Directive regarding building energy performance.

Last year’s negotiations about revisions to the EnEV were prolonged and heated. The ordinance that was passed is a testament both to the collaborative abilities of the government’s various factions, and to the importance the German public places on the country’s Energy Transition.

On May 1 of this year, the changes that were approved last October came into force. New requirements relating to building energy labeling and heating systems are now in effect, but a key provision of the so-called EnEV 2014 — tighter requirements for building energy efficiency — will not be in force until 2016.

The origins of the EnEV can be traced back to the mid-1970s when, as a result of the Arab oil embargo, Germany passed its first building insulation ordinance. Over the ensuing decades, insulation requirements were periodically strengthened, and in 2002 the ordinance was expanded to cover building heating systems.

Energy performance labels for buildings

In response to the European Union’s first “Energy Performance in Buildings Directive,” Germany developed a labeling system (Energieausweis) for building energy performance that was incorporated into EnEV 2007. The goals included making energy information about buildings more transparent and facilitating decisions about energy efficiency improvements.

In 2009, revisions to the EnEV tightened efficiency requirements by 30% over EnEV 2007. For the first time a reference building was defined, against which actual buildings could be measured. As part of the government’s effort to integrate its energy and climate programs, EnEV 2009 also set limits on the allowable primary (source) energy used by new buildings. Calculations to determine primary energy use are based on the characteristics of the building envelope, and on the energy requirements of the building’s heating, cooling, ventilation, and lighting systems. A multiplier, the “primary energy factor,” is used to estimate the primary energy used by the building, and the corresponding CO2 emissions.

The EnEV 2014 amendments that have just come into effect relate primarily to building energy performance certificates, heating systems and — eventually — to the energy efficiency of new buildings.

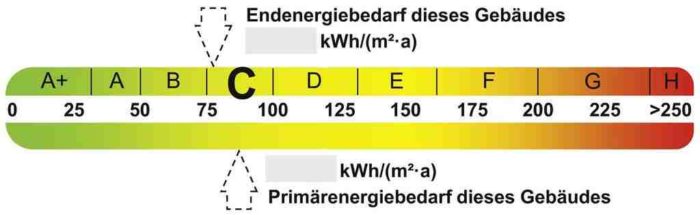

Germany’s building energy labels have received a modest makeover. The new format adds a set of categories, A+ through H, to complement what had been a multi-hued numerical scale. The categories are consistent with the classifications already used in Europe for appliances and electronics. Each certificate must now be registered with the government’s Institute for Building Technology (Deutsches Institut für Bautechnik), and the registration number indicated on the certificate. Building data collected via the registration process will contribute to a database similar to the EPA’s Portfolio Manager. The requirements for listing recommended energy efficiency improvements have been strengthened.

The conditions for communicating about and transferring energy labels are also now more rigorous. Real estate advertisements must include information such as the primary and end energy values, as well as the efficiency category. Realtors, building owners and managers are now required to present the energy certificate when first showing a building to prospective buyers or renters. EnEV 2014 also initiates a system of random checks on energy labels for quality assurance.

Heating equipment needs to be replaced after 30 years

Several of the new EnEV provisions relate to heating systems in existing buildings. All oil and gas boilers installed before 1985 must be taken out of service by 2015. Heating systems installed after 1985 have to be replaced after thirty years, with the exception of low temperature and condensing boilers.

Owner-occupants of one- and two-family homes are exempt from this requirement.

New buildings will aim for “nearly net zero”

The tighter building efficiency standards that take effect in 2016 will bring Germany closer to the EU’s goal of all new construction being nearly net zero by 2021. In 2016, the allowable primary energy demand of new buildings is mandated to be 25% lower than the reference building described in EnEV 2009. This reduction will be achieved in part through a 20% increase in insulation values for non-residential buildings. However, the more rigorous insulation requirements will not apply to existing buildings. Germany’s Ministry of Transport, Building and Urban Affairs has stated that “the requirements for upgrading the envelope components of existing buildings as described in EnEV 2009 are already very demanding. The energy savings resulting from further tightening these requirements would likely be low.”

The roll-out of EnEV 2014 has not generally been front page news in Germany, perhaps because the most significant provisions do not take effect until 2016. I did see an article in the business-oriented newspaper Handelsblatt that criticized the government’s increasingly demanding energy requirements, and claimed that the coming standards for insulation will raise the cost of new construction by 8% (a figure that I find questionable). Representatives of the real estate industry have objected to the new requirements relating to communicating and transferring energy certificates, which they argue will significantly increase the cost of marketing, selling, and renting properties.

Energy auditors’ concerns

I subscribe to a monthly magazine for energy consultants, and the discussion of EnEV 2014 in that arena has centered largely on the details of implementation. While some auditors appreciate the greater clarity afforded by the categorization scheme, others fear that homeowners will be dismayed to learn that after spending thousands of euros on efficiency improvements, their house could only receive a grade of “C.”

Some in the auditing community are lamenting the increased administrative burden that registering energy certificates imposes. Others have raised questions about the security of the data that will be uploaded. (Germans generally seem to be more concerned than Americans about the protection of privacy online). And some auditors are apparently experiencing glitches with the government’s online tool for registering and printing energy certificates. All energy consultants who generate certificates are having to upgrade their software, because the many software companies that serve auditors are issuing updates to accommodate the government’s new regulations.

Issuing energy certificates for buildings without a site visit

Some criticisms from the auditing community are directed not just at the revised EnEV, but also at the way in which the values on energy certificates are derived. When the certificates were first mandated in 2007, several compromises were made in an effort to minimize the financial burden.

The ordinance did not require on-site energy evaluations, and it allowed two processes for calculating building energy use: one based on demand, and the other on consumption. The demand-based version had previously required that an energy auditor visit a building to evaluate its energy-related characteristics. This resulted in accurate certificates with considered recommendations for efficiency improvements.

The consumption-based version of the certificate bases the calculations on utility bills and a rough analysis of building parameters. Websites now offer both types of energy certificates generated from information that customers provide online. For example, at Energireausweis-Vorschau, a consumption-based energy certificate costs €69, and a demand-based certificate €189. Sites like this provide stiff competition for energy consultants doing on-site audits, who must convince prospective customers that the certificates they supply are more valuable.

Renewable energy mandates

Notwithstanding the complaints from different quarters, the latest EnEV does not appear to have provoked a significant amount of pushback. Germans seem generally willing to make modest sacrifices in the name of energy independence and climate protection.

A more contentious debate that is currently taking place concerns revisions to the country’s Renewable Energy Sources Act (the Erneuerbare-Energien-Gesetz). The government is struggling to find the appropriate balance between continuing to support its ambitious Energy Transition, and addressing concerns of corporations and citizens relating primarily to costs. The results of the current negotiations will influence how much Germans pay for retail electricity, how much producers of renewable energy are paid, and how the German landscape will continue to be transformed by wind turbines, PV installations, biogas plants, and transmission lines.

Andrew Dey’s background includes carpentry, contracting, and project management. For the past six years he has provided construction consulting services to clients in New Hampshire, Vermont, and Massachusetts. He is passionate about retrofitting existing buildings — including his own house — for greater energy efficiency. His blog is called Snapshots from Berlin.

Weekly Newsletter

Get building science and energy efficiency advice, plus special offers, in your inbox.

0 Comments

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in