I am honored to have been invited to contribute a regular column on the topic of carbon to Green Building Advisor, although I do so with some trepidation. This crowd knows its stuff; and I feel a little out of practice. I was an architect for decades, then a real estate developer, and a prefabricated housing promoter. I even tried my hand at building tiny homes before realizing I was better suited to writing and teaching sustainable design at Toronto Metropolitan University. In 2021, I authored the book Living the 1.5 Degree Lifestyle: Why Individual Climate Action Matters More Than Ever, which describes my attempt to reduce my “lifestyle” carbon emissions—those I have some control over—to less than 2.5 metric tons per year. I did all the usual carbon footprint things: I gave up red meat, rode my bike instead of driving, and bought less stuff.

Assessing emission sources

But at the end of the year, it became clear that it mattered less what I did than where I lived. I could give up driving because I lived in a 110-year-old “streetcar suburb” where everything I needed was close by, and I never actually needed to drive. My electricity is almost carbon-free, coming from hydro and nuclear. I had subdivided my 100-year-old house into two units eight years ago, so my wife and I occupied just 1200 sq. ft. My carbon footprint was smallish because of the design of the built environment: how much space I occupied, how I got around, and how it was all powered.

I didn’t buy much stuff, but the stuff I owned was problematic because of the carbon emissions from making it. Take my iPhone 11 Pro. The phone is small and light, at 6.63 oz. or 188 g., and sips electricity. Apple publishes carbon lifecycle assessments of its products, which show the 11 Pro having lifecycle carbon emissions of 80 kg. or 425 times the phone’s weight. Apple says that 86% of the emissions come from production and transport and 13% from use.

But Apple bases the carbon emissions from use on a North American mix of electric power, much of which is generated with fossil fuels. My power comes from hydro and nuclear, so my carbon emissions from using the phone are close to zero. That means that for my phone, nearly 100% of its carbon emissions come from the production and transport of the phone components.

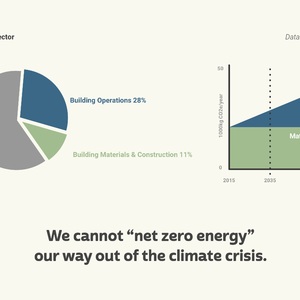

The same rule applies to your car or your home; when powered by fossil fuels, the operating emissions dominate. But as our homes get more efficient and we electrify everything, the emissions from manufacturing your new F-150 Lightning or “net-zero” home come to dominate the lifecycle picture.

Rethinking the terminology

We used to call the energy it took to make something “embodied energy,” so when we started talking carbon, it seemed natural to call it “embodied carbon.” But it’s a confusing term. The definition of embodied is “included or contained as a constituent part.” Carbon emissions are neither contained nor a constituent part; they have been released into the atmosphere.

If the carbon were embodied in my iPhone, it would weigh 176 pounds; I may lift weights occasionally, but I would have trouble with that. If embodied in the F-150 lightning, it would cause bridge collapses. No wonder people don’t understand it. This is why architects Elrond Burrell, Jorge Chapa, and I, sitting around the Twitter water cooler in 2019, came up with the term “upfront carbon,” which is carbon emitted upfront before anyone sets foot in the building.

Four years later, I am not certain that “upfront carbon” vs. “operating carbon” tells the whole story. According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), we have a carbon budget, meaning a maximum number of gigatons of emissions that we can add to the atmosphere before we hit 1.5° or 2°C of warming. Every kg. of carbon we emit goes against that budget. It matters now. These days, I am apt to say we have “now” emissions and “later” emissions.

Upfront carbon is released in varying amounts from every building material and product, even wood. That’s why how much we build is almost as important as what we build it out of. Martin Holladay noted this in the preface of his book, “Musings of an Energy Nerd”: “What the planet really needs is for all of us to buy less stuff, including so-called green building materials, and to strive, every year, to burn less fossil fuels than the year before.” These are words to live by and are key to reducing both operating and upfront carbon emissions. Martin Holladay talks of modesty; the French call it sobriety; the IPCC boringly calls it “demand-side mitigation,” I call it sufficiency. But we all are saying the same thing: we need less but better.

Many are now saying we have blown 1.5° and maybe even 2°C of warming and that we can’t do anything about it. Others say we need to suck carbon dioxide out of the air, and we need hydrogen, fusion, and technological breakthroughs to solve this.

I don’t believe them.

We know what to do

We know how to build houses with zero operating emissions right now. We know how to put them in communities where we don’t have to drive pickup trucks for miles to get a quart of milk. We know how to pull heat out of the air and cook with magnetism; we don’t have to burn things anymore. We know how to choose materials with lower upfront carbon emissions, but we also know that the best way to reduce them is to use less stuff.

Buckminster Fuller once wrote, “How much does your building weigh? A question often used to challenge architects to consider how efficiently materials were used for the space enclosed.” To bring Bucky up to date, we must ask ourselves, “How much do our upfront carbon emissions weigh?” Because when you look at the world through the lens of upfront carbon, it changes everything. This is what I plan to report on going forward.

________________________________________________________________________

Lloyd Alter is a former architect and developer. His journalism career includes 15-plus years as design editor at Treehugger.com. Today he teaches sustainable design at Toronto Metropolitan University. His work can be found at Carbon Upfront.

Weekly Newsletter

Get building science and energy efficiency advice, plus special offers, in your inbox.

23 Comments

Welcome, Lloyd

Look forward to your efforts on GBA. The green lifestyle is elusive and will require more effort by more people if we are to make progress. More efficient buildings are a start, the building envelope must come first. All of the expensive HVAC gadgetry will not cover up a poorly designed and built structure.

Thank you,

Doug

Lloyd,

I've enjoyed your articles on treehugger and look forward to your contributions here on GBA. Are you still writing for Treehugger too?

Scott

I am no longer writing for Treehugger, but I can be found right here from now on.

Welcome, Lloyd. I look forward to reading your new column!

Thank you Michael, I am now hanging out with a tough crowd but I think it will be fun.

What great news. Something to look forward to!

Sounds like an interesting column.

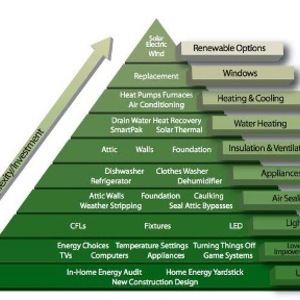

I hope it might tackle some hard questions, like how do we make the move to efficient structures and systems when making those moves involves upfront carbon expenditures. Even renewables have this fundamental issue: they cost a lot of carbon now to build, but in theory lead to a cleaner future.

Decisions are easy when two equally performing options have different upfront carbon (e.g. wood fiber insulation vs xps) but things are far less clear when the question becomes "should we do this at all" (e.g. add the extra R-30, or buy the fanciest most efficient HVAC system imported from across the seas).

Welcome Lloyd!

Your chosen beat is perfect.

I know you'll enjoy working with Kiley and the super-smart and respectful community that makes GBA so cool.

Looking forward to your posts.

Welcome aboard Lloyd! I've loved your work at TreeHugger and It'll be great to have you here with the GBA team.

Without a doubt my biggest gripe with GBA is that site selection is almost always glossed over when it it is perhaps the most critical detail to holistic sustainability of a home. I'm looking forward to seeing your work and (fingers crossed) its impact on other contributors and editorial staff here.

Thanks for the note. I will be spending a few pixels on that!

Welcome Lloyd! As much as I value the technical information found on this website, there isn’t enough focus on what’s getting built and where it’s getting built even though it is what matters the most when it comes to environmental impact (and affordability for those who care). Sadly the least sustainable model; the single-family home that’s highly car dependent remains the norm in most green building articles.

It will be great to have a writer who can do the math and not just, say, try to sell us on the virtues of a "Leed Platinum" 7,500 sqft foot single family home with a 3-car garage and corresponding number of cars!

https://www.usgbc.org/projects/gpd-346-highland?view=overview

Your writings make me slightly uncomfortable and knock me off the high horse I climbed onto because of the latest energy efficiency project I have taken on.... Exactly what we all need!! Thanks for the constant reminder that we need to consume less, and that we can enjoy life just as much while consuming less!

Where my organization works in Africa, entire villages get by with a few solar panels, local building materials and enormous elbow grease. When I consider the amount of upfront and operating carbon produced per capita by most of the world's population compared to my own, it is stunning. It is clearly not fair to these folks or to our grandchildren that we use up so much of the world's resources and leave so much carbon in the atmosphere, especially when they are left with the greatest burden from such behavior.

Looking forward to your continuing to challenge us !

I was also thinking that the primary chemical involved in the Ohio train derailment was vinyl chloride-and the main use for it is PVC building materials. Thus, we should also be thinking about how our building techniques and volumes create other risks and externalities besides climate change.

--- “What the planet really needs is for all of us to buy less stuff, including so-called green building materials..." Martin Holladay talks of modesty; the French call it sobriety; the IPCC boringly calls it “demand-side mitigation,” I call it sufficiency. But we all are saying the same thing: we need less but better. ---

What this really means is a smaller economy. That is a very, very scary thought to Capitalists, because all Capitalists have is capital to invest in production of stuff that then needs to be consumed by the masses, if their capital is to continue to grow.

We have to be honest and upfront about the fundamental conflict between a capitalist economy and environmental sustainability or we'll never really find a way to solve the long term problems.

in Europe they talk about "degrowth" but you cannot do that in North America. Growth is everything!

Very true. Some topics are just too hot.

Actually, I'm an American living semi-permanently in rural France. I'd like to see a comparison of the CO2/person for my village compared to an American suburb. The people around me aren't particularly environmentally conscious. But culturally, there are so many things that favor simpler living. People here prioritize, desire, locally farmed food, for example. And there's no pressure to demonstrate "success" by building a huge house. In fact, it's rather a crass thing to do. Lovingly restoring some old one is fine of course.

That said, people here nowadays probably drive quite a bit more than they did a generation back, though nothing like in the States. My only real complaint is that France, like the USA, has a political/cultural elite that is happy to tell us we should ride bicycles and wear sweaters indoors while they continue to fly to the latest Climate Change Conference, Davos, or a football match in the Emirates in their private jets.

I guess we can't all have presidents like Uruguay's Jose Murica.

jgsg,

"What this really means is a smaller economy. That is a very, very scary thought to Capitalists"

Definitely - but even to those sympathetic to the idea it poses some big hurdles.

Even with continued growth most industrialized nations are facing demographic problems related to increases in the proportion of their population that is elderly and need supporting.

It's also something countries are reticent to do on their own, as in a global economy it means a disproportionately large change in the lifestyle of their citizens, when others aren't pursuing the same policies and continue to grow.

Then there is the problem of how you get the rich on-board? What is their incentive to make the same sacrifices that the rest of the population might decide to make when their wealth is transnational, and they can simply continue growth elsewhere?

Jolly G: what you are saying is true to a point, in terms of physical "stuff"....physical things and materials.. However, the percentage of the economy that is knowledge based- intellectual property and intangible items- is growing far faster than the part of the economy associated with the manufacture and transport of stuff. And of course, there are capitalists that make a hell of a lot of money financing these intangible things. So there can be economic growth without masssive increases in carbon. It is true that the internet takes a lot of power to run (data centers), but I do not think these power requriements are anywhere near those needed to make and deliver stuff like steel and concrete, etc and some of it can be delivered from renewable sources.

A perfect example is how modern teens spend their marginal income compared to how I spent mine at that age in the 1970's...They buy apps and web based "tools"; I bought engine blocks, wrench sets and equipment made of steel. I think I used a lot more up front and operating energy than they do.

The issue I ponder is how does the developing world get to share in the prosperity of the earth more fairly without exploding carbon emissions. In places like the villages where my group workis in Africa, people use almost no carbon based energy and have almost no "stuff", but they want and deserve more: more nourishing food and clean water, materials to build strurdy houses and electricity to run basic things....They will choose growth so all of us will need to figure out how to facilitate that in a responsible way.

nick, I understand your point about intangible "products". But... since 1960

Cars per capita has nearly doubled,

and vehicle miles driven per person has far more than doubled,

and after a dip during the Obama presidency is rising again.

Average new house size has more than doubled,

even while household size has dropped.

We still produce the same amount of municipal solid waste per capita as we did in 1960, while also producing a whole new pile of material that gets recycled. So our efforts to create a culture/ecosystem of recycling has only served to stop the growth of, but not reduce the amount of garbage we produce.

Practically all of us now carry on our bodies an array of electronic gadgets designed to go obsolete in 2-3 years, gadgets which contain toxic heavy metals and often end up in landfills or being "recycled" in uncontrolled conditions by desperately poor people in places like India. Americans discard apx 100-120 million cell phones each year. These objects didn't even exist 20 years ago. It's a whole new class of consumables, of garbage.

So when it comes down to it, we are actually consuming more physical stuff than ever before, no matter the wonders of the new digital economy.

There are also almost twice as many Americans as there were in 1960.

Sorry if I sound like a downer. I probably need another cup of coffee. Not so jolly today. I just don't think we grasp the scale of our consumerism, and what it means in economic terms, to change that reality.

edit - And your final paragraph is the most important of all. Everyone in the world deserves access to the resources that make for healthy, productive, secure lives. Unfortunately I think what the owners of the means of production see when they look at those population groups is just more markets to sell more stuff and make more garbage.

Well one bit of hope is that the people I have met and worked with in developing communities (and many young people all over) seem to have a pretty good understanding of how important it is to protect the enviornment (both near and far) and their consumerism is relatively modest. They are demanding a say in how it all develops so perhaps they can do a better job in developing the future than we have !

>"However, the percentage of the economy that is knowledge based- intellectual property and intangible items- is growing far faster than the part of the economy associated with the manufacture and transport of stuff."

At the risk of making a statement without real numbers to support it, I think there are arguments that we've simply off-shored the material economy. The 'intellectual' economy can then be seen as the next phase of development—ON TOP of the underlying material economy, NOT IN LEUI of it. (Basically what Jolly green is saying).

A concept we're circling around here is "decoupling". Can we truly decouple economic growth from environmental consumption?

And it's not just about carbon. I recently listened to a podcast where someone pointed out carbon is our largest waste item by weight. Well yeah I guess that makes sense! They argued that carbon and global warming is not the fundamental problem but rather a symptom of the larger systemic problem of "ecological overshoot". Carbon is not our only environmental challenge by a long shot.

I sometimes think we can transition towards a sci-fi-like vision of a super efficient society that has found harmony with the environment, but other times I fear that the 'harmony' element will be entirely ignored and the search for a brute force technological fix will override other necessary fundamental changes to our business as usual model. A 1 to 1 replacement probably won't cut it.

Technologies are tools, not solutions. Changes in our relationships will be the solution.

Good to have you here, Lloyd.

I share your obsession w/ whatever we're calling it. "Unavoidable carbon"? My current squeaky wheel is don't do things with a carbon payoff of more than a few years.

"unavoidable carbon" is good.

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in