Every single one of us — those of us who lives indoors — is cohabiting with all manner of living uninvited guests: bacteria, fungi, insects, plants, and even rodents. And many of them appear “in nature” only inside our homes. Wouldn’t the healthiest home be the one purged of all these interlopers?

The answer, according to Rob Dunn, is a resounding no.

Rob Dunn, professor of applied ecology at North Carolina State University, has been researching this particular habitat — our homes — for most of his professional career. His new book, Never Home Alone: From Microbes to Millipedes, Camel Crickets, and Honeybees, the Natural History of Where We Live, is a fascinating research-driven story of academic adventure. I am serious: this book is the first nonfiction page-turner I have read in a very long time.

Guests that play a role

Chapter by chapter, Dunn makes the case for the important role all these guests play in indoor habitats. And that is key: we like to think of our homes as completely separate environments just for us, decoupled from the “wild.” Nothing could be further from the truth, and (as conveyed in Chapter 1, “Wonder”) no one has so relentlessly studied our indoor environments since Antony Leeuwenhoek:

[Paraphrased from Dunn] – Sometime in 1676, Leeuwenhoek walked the block and half to the market to buy black pepper. He did not sprinkle the pepper on his food. He carefully added a third of an ounce to a teacup of water, checking on the peppercorns again and again. After three weeks, Leeuwenhoek made a pivotal decision: he examined the now cloudy water with a very crude microscope and saw “…an incredible number of very little animals of diverse kinds.”

Unlike many scientists then and since, Leeuwenhoek focused on the world around him, mostly in his home and neighborhood: fleas, flies, fungi. More than four hundred and fifty years later, Dunn made a pivotal decision of his own: not to study alluring and exotic tropical or remote mountain habitats, but instead to study the humdrum home.

Quotes that provide a glimpse of the book’s topics

Everyone in the building community should be thanking Dunn for that decision. Here, chapter by chapter, are reasons why:

Chapter 2: “The Hot Spring in the Basement.” This chapter is focused on thermally tolerant bacteria in tank water heaters and gene sequencing: “The results [of gene sequencing to identify all manner of species in samples] would prove surprising. They were surprising both in terms of the many species we found and in terms of those that were missing.”

Chapter 4: “Absence as a Disease.” Chapter 4 is largely about a study of Amish and Hutterite children in the U.S.. The author discusses the practice of traditional agriculture by the former and industrial agriculture by the latter, and their drastically different incidence of inflammatory diseases, and immune systems: “Imagine there is a certain number of bacteria to which you need to be exposed to stay healthy… [T]he more plants and animals and soil you interact with, the more likely you will pick up some of those key bacteria. The fewer kinds you are exposed to, the less likely you get the right ones, the ones that activate your innate immune system…”

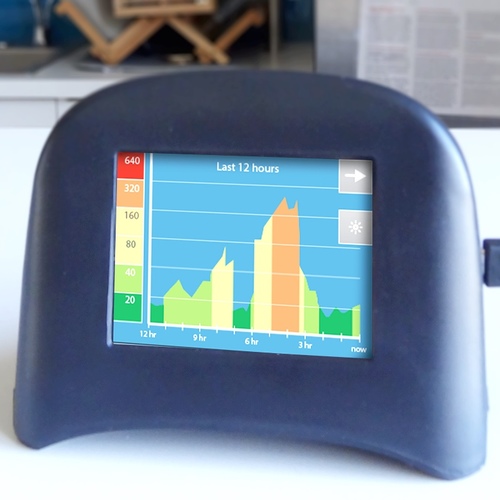

Chapter 5: “Bathing in a Stream of Life.” This chapter is all about just what lives in our showerheads and how different the species are based on how “treated” the water is: “The showerhead is one of the simplest ecosystems in your house… The average showerhead has dozens…of species in it… some microbial strands that may make you sick; others may make you happy…

“But what, then, should you do about your showerhead? We don’t know yet, but I’ll [Dunn] tell you what I think … I think that while some Mycobacterium species are beneficial the average species is a little bit of trouble, particularly for immune-compromised individuals. I think that these bad-news Mycobacterium species become more common the more we try to kill everything in our water, and in doing so, kill off Mycobacterium’s competition.”

Chapter 6: “The Problem with Abundance.” This chapter focuses on biological growth associated with building materials and particularly research by Birgitte Andersen, an expert on the fungi of houses at the Technical University of Denmark: “[Andersen found that] … Neosartorya hiratsukae was on every single sheet of drywall, regardless of type, regardless of which store it came from, and regardless of which company it was made by.” [This fungus has recently been implicated in the complex mix of causes of Parkinson’s disease.]

Chapter 7: “The Farsighted Ecologist.” This chapter at first seems to be about camel crickets and their long association with indoor habitats, but as the quote below reveals, it’s really about the nature of scientific endeavor: “What I’ve [Dunn] taken away from our work, so far… is that when you see a species in your home, you should study it. You should pay attention. Don’t assume someone else has already figured everything out.”

Chapter 8: “The Problem with Cockroaches is Us.” It’s pretty obvious what this chapter is about, but Dunn’s assessment of these truly despised insects is not as obvious: “Whatever the reason we don’t like them, we really don’t have that much to fear from them. German cockroaches can carry pathogens, it is true, but not any more so than your neighbors or children carry them. Also, no cases have yet been documented in which someone has actually gotten sick from a pathogen spread by a cockroach, whereas people get sick from pathogens spread by other humans.”

An indoor garden

Every chapter in this book is a revelation about where we live, who we live with, and their roles in our health and wellbeing.

Rob Dunn’s work can be summed up with this quote from Chapter 3:“What we really want in our homes is a kind of garden. In a garden you kill the weeds and pests, but you take care of the diverse species you are trying to grow.”

Maybe Taunton Press can work with Dunn on merging Fine Homebuilding with Fine Gardening, using GBA to cultivate healthier approaches to how we think and act on indoor environmental quality.

Read this book; you may never enjoy learning quite as much.

In addition to acting as GBA’s technical director, Peter Yost is the Vice President for Technical Services at BuildingGreen in Brattleboro, Vermont. On January 1, 2019, Yost will bid BuildingGreen adieu and open his new consulting company, Building-Wright, in Brattleboro, Vermont. He has been building, researching, teaching, writing, and consulting on high-performance homes for more than twenty years. An experienced trainer and consultant, he’s been recognized as NAHB Educator of the Year. Do you have a building science puzzle? Contact Pete here.

Weekly Newsletter

Get building science and energy efficiency advice, plus special offers, in your inbox.

2 Comments

We tip the hat to you Peter! Hope you still read and chime in when needed. Thank you.

Sounds like a fascinating book. Thanks, Peter.

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in