More than 3.6 million electric cars are driving around the U.S., but if you live in an apartment, finding an available charger isn’t always easy. Grocery stores and shopping centers might have a few, but charging takes time and the spaces may be taken or inconvenient.

Several states and cities, aiming to expand EV use, are now trying to lift that barrier to ownership with “right to charge” laws.

Illinois’ governor signed the latest right-to-charge law in June, requiring that all parking spots at new homes and multiunit dwellings be wired so they’re ready for EV chargers to be installed. Colorado, Florida, New York and other states have passed similar laws in recent years.

But having wiring in place for charging is only the first step to expanding EV use. Apartment building managers, condo associations and residents are now trying to figure out how to make charging efficient, affordable and available to everyone who needs it when they need it.

Electric cars can benefit urban dwellers

As a civil engineer who focuses on transportation, I study ways to make the shift to electric vehicles equitable, and I believe that planning for multiunit dwelling charging and accessibility is smart policy for cities.

Transitioning away from fossil-fueled vehicles to electric vehicles has benefits for the environment and the health of urban residents. It reduces tailpipe emissions, which can cause respiratory problems and warm the climate; it mitigates noise; and it improves urban air quality and quality of life.

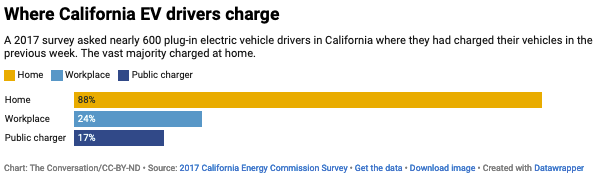

Surveys show most EV drivers charge at home, where electricity rates are lower than at public chargers and there is less competition for charging spots. In California, the leading state for EVs, 88% of early adopters of battery electric cars said they were able to charge at home, and workplace and public charging represented just 24% and 17% of their charging sessions, respectively. Nationwide, about 50% to 80% of all battery electric car charging sessions take place at home.

Yet almost a quarter of all U.S. housing structures have more than one dwelling unit, according to the 2019 American Housing Survey. In California, 32.5% of urban dwellings have multiple units, and only a third of those units include access to a personal garage where a charger could be installed.

Even if installing a personal charger is an option, it can be expensive in a multiunit dwelling if wiring isn’t already in place. And it often comes with other obstacles, including the potential need for electrical upgrades or challenges from homeowner association rules and restrictions. Installing chargers can involve numerous stakeholders who can impede the process–lot owners, tenants, homeowners associations, property managers, electric utilities and local governments.

However, if a 240-volt outlet is already available, basic charger installation drops to a few hundred dollars.

Right-to-charge laws aims for ubiquitous home charging

Right-to-charge laws aim to streamline home charging access as new buildings go up.

Illinois’ new Electric Vehicle Charging Act requires that 100% of parking spaces at new homes and multiunit dwellings be ready for electric car charging, with a conduit and reserved capacity to easily install charging infrastructure. The new law also gives renters and condominium owners in new buildings a right to install chargers without unreasonable restriction from landlords and homeowner associations.

California, Colorado, Florida, Hawaii, Maryland, New Jersey, New York, Oregon and Virginia also have right-to-charge laws designed to make residential community charging deployment easier, as do several U.S. cities including Seattle and Washington, D.C. Most apply only to owner-occupied buildings, but a few, including California’s and Colorado’s, also apply to rental buildings.

Chicago officials have considered an ordinance that would include existing buildings, too.

Sharing chargers can reduce the cost

There are several steps communities can take to increase access to chargers and reduce the cost to residents.

In a new study, my colleagues and I looked at how to design shared charging for an apartment building with scheduling that works for everyone. By sharing chargers, residential communities can reduce the costs associated with charger installation and use.

The biggest challenge to shared charging is often scheduling. We found that a centralized charging management system that suggests charging times for each electric car owner that aligns with the owner’s travel schedule and the amount of charge needed can work–providing there are enough chargers.

In a typical multiunit dwelling in Chicago–with an average of 14 cars in the parking lot–a small community charging hub with two level 2 chargers, the type common in homes and office buildings, can cover daily residential recharging demand at a cost of about 15 cents per kilowatt-hour. But having only two chargers means residents are waiting on average 2.2 hours to charge.

A larger charging hub with eight level 2 chargers in the same city avoids the delay but increases the cost of charging to 21 cents per kWh because of upfront cost of purchasing and installing the chargers. To put that into context, the average electricity cost for Chicago residents is 16 cents per kWh.

The future of charging management at multiunit dwellings will be automated for efficiency, with a computer or artificial intelligence determining the most efficient schedule for charging. Optimized scheduling can be responsive to the times renewable electricity generation sources are producing the most power–midday for solar energy, for example–and to dynamic electricity pricing. Automation can also eliminate delays for drivers while saving money and reducing the burden on the electric grid.

The current limited access to home charging in many cities constrains electric vehicle adoption, slows down the decarbonization of U.S. transportation and exacerbates inequities in electric vehicle ownership. I believe efforts to expand charging in multidwelling buildings can help lift some of the biggest barriers and help reduce noise and pollution in urban cores at the same time.

Eleftheria Kontou is an assistant professor of civil and environmental engineering at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. This article was originally published at The Conversation.

Weekly Newsletter

Get building science and energy efficiency advice, plus special offers, in your inbox.

10 Comments

While mandating charging ability in new buildings is a good idea, it does not help the 100 percent of us who live in existing buildings.

When I pondered getting an EV 2 years ago, I did the math and realized that I so rarely drive more than 250 miles in a day, that it was a perfect fit.

I installed a 20 amp 240 volt charger outside my garage, and it has always met my needs. As it turns out, with my 15 mile daily round trip, level 1 [120v] charging would have been fine.

My car will charge at about 5 miles an hour on 120 volts. If plugged in every night, that would add up to 40 miles every night.

I see this conversation on EV message boards constantly, 'which charger should i buy?' always a 40 amp 240 volt. Overkill

Of the various places I have lived in the last 40 years, only one[a large apartment building] where I lived for 4 months would not have allowed me to drop a cord out the window. For about 3 years of the last 40 have I had a commute of more than 40 miles a day. In many of those cases I could have charged at work. This is, mind you, time travelling when I was not making EV related decisions.

If you live in a urbanish multi unit building, what is your daily commute? Probably less than a suburbanite.

Here is my point, level one charging will suffice in 90 percent of that 25 percent of people who don't live in detached single family dwellings.

Thinking about getting level one charging in existing buildings would be an effective, affordable way to get the job done.

Gus makes some good points on Level 1 vs 2. That said, I used Level 1 for a few months at home, then switched over to Level 2 for a few reasons:

1. Level 2 is inherently more efficient as the vehicle will be a in charge state for a shorter period. This means charging overhead (300 watts, or more if the battery is also conditioning) would be reduced. If you use the example of an EV charging at 12 amps@120V (level 1) vs 12 amps@220V (level 2), then level 1 for 6 hours might incur 1.8 kW of overhead, where 3 hours of Level 2 would incur 1/2 of that overhead, 0.9 kW, to get the same charge into the EV.

If you multiple x 1000s of EVs, that is quite significant.

2. To precondition the cabin at level 1 and -25 C with EVs like the later model LEAF, the cabin will not reach the target temp as there is simply not enough watts there (most level 1 is limited to 12 amps@120V) to both run the car's overhead and heat the cabin. Again, Level 2 will do a much better job, and run for shorter time to do it. You would assume that the car would just use the high voltage pack to run heat when plugged in, but it does not as this would potentially deplete the charge...it uses power available from the AC to DC inverter if plugged in. Tesla may have a way around this in car setup but if so, I'm not aware of it. With Tesla now shipping LFP cells in many markets, they need to be heated above 0 C to even start charging..so again, you'd want Level 2 there to shorten the conditioning time in colder climates with an EV parked outside.

I suspect that a plug standard in the 20 amp range at 220V should be a minimum target as you can charge at 16 amps, adding about 12 miles of range or more to an EV in an hour (assuming a car). EVs are becoming more efficient year over year (like the Model 3 and Hyundai Ioniq 6), so this will only increase.

This is where the problem lies in level 1 only. Larger EVs can't even maintain the battery conditioning on 120V in the winter to enable charging.

From what I can see, conditioning , or bringing the battery up to temp to charge, is a big thing for rapid charging. I am not sure whether that matters for AC charging.

Preheating the cabin is certainly nice[and in my Kia pretty required for the defrosters to get up to speed] but you can do it whether it is plugged in or not. Of course not plugged in you eat into range, which is simply not an issue in the majority of cases.

I would have to look into whether level one is really that much less efficient than level two

While I do not disagree that 240 volt is preferred, look at what we are talking about.

In 'x' years most people will have EV's[with any luck]

You have a normal suburban apartment building with say 12-20 apartments in a building. You are looking at 50-100kw of added load[from an electrical wiring standpoint, not actual load, that will not happen] plus all those breaker slots[twice as many as 120v]

Say you were writing a regulation for such buildings. Would it not make sense in world with assigned parking spaces that a simple 120 volt outlet at every space [or every other if you get two spaces or whatever]

Imagine sitting in a meeting with a recalcitrant developer and saying, wait, you cannot run a friggin outlet to every parking space?

I am making this point as I mentioned earlier, everyone assumes they need a giant charger, and they just don't, everyone I see is installing a 40a charger, start doing that math. The amount of copper is mind boggling.

Another thought, having seen the code for underground wiring depth, with the advent of GFCI breakers, maybe a code exception from depth or conduit or concrete or whatever for 20 amp and below GFCI protected wiring would help the cost of adding outlets

A 20 A, 240 V circuit doesn't require any more copper than a 20 A, 120 V circuit. That's probably the sweet spot. Fast enough for most scenarios, more efficient than level 1, but still cheap to install.

A single one does not require more copper. 20 does. And twice as much box space. The single family is not the real problem here

By "box space" you mean the panel? The outlet box can be a regular single-gang. And panels are pretty cheap.

And what copper are you thinking of? The feeders are going to be Al.

"A single one does not require more copper. 20 does."

How so?

20 amps@220V as a minimum. Agree 100%.

Tesla is shipping cars with LFP chemistry and those will not charge at all if the pack is below 0 C. In that case, level 1 or 2, or DC, …it will need to be heated to charge.

Don’t forget the issue of overhead which makes level 1 charging substantially less efficient than level 2.

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in