Editor’s note: This post is one of a series by Eric Whetzel about the design and construction of his house in Palatine, Illinois, a suburb of Chicago. A list of Eric’s previous posts appears below. For more details and more photos, see Eric’s blog, Kimchi & Kraut.

We wanted the process of creating our new home to be fun, so from the outset we approached the build as a mix of science and art.

For the structure, this meant utilizing building science research to properly air seal, insulate, and ventilate to ensure that we ended up with a house that’s hopefully durable, stingy with its use of electricity, and that functions well on a daily basis for many years to come.

In terms of design, it meant spending an inordinate amount of time on the floor plan, carefully defining how we would move through and live in the structure, while also carefully considering the seemingly infinite options when it comes to finishes, both for the interior and the exterior of the home (with an emphasis on low or no VOC products to protect indoor air quality).

With most of the wall assembly details finally in place, putting up the charred cedar siding represented the first real transition from science to art. And with Passive House details mostly taken care of, we could begin to make decisions in real time regarding how we wanted the house to look, both inside and out.

Massing: basic forms

Our house is a basic box with a gable roof (long sides face north and south with the gable ends to the east and west). It’s not unlike the basic form most children would come up with if prompted to draw a house. We really like the simplicity of this kind of roof style for aesthetic reasons, but also for the ease of installation and for durability.

Bronwyn Barry has even coined a hashtag for this use of very basic forms, #BoxyButBeautiful, especially popular with Passive House design since it can help eliminate thermal bridges while making air sealing more straightforward.

We tried to avoid having the garage as part of the front of the house, in particular having the garage door facing the street (a look I’m not fond of), but physical limitations, in terms of the lot itself, left us with little choice in the matter. So rather than repeat the gable roofline of the house, we went with a shed roof for the garage. The shed roof adds some visual interest, while it also ensures that any rainfall in this area immediately gets sent to the north side of the house where we want it—away from the foundation as well as bypassing the driveway altogether (water flows to the north on our street).

We also felt that these two rooflines fit in well with our Urban Rustic design aesthetic. As a mash-up between early 20th century city and farm, both the simple gable and stark shed rooflines would be equally at home in an agricultural setting or on a densely packed inner city block.

In addition, it was important to us to have some fun with color, so on the exterior using black charred cedar with some natural highlights would give us the bold look we were going for, while accent walls inside with bright, playful colors would help bring the interior to life.

Siding layout for our charred cedar

Since we were building custom, rather than working within the constraints of tract housing in a larger subdivision (as we did with our first house) where many of the design choices are already made for you, we knew we wanted to take some chances in terms of materials and layout.

It also helps that we’re in a neighborhood with mixed architectural styles, including single-family homes and townhomes, with structures and exteriors running the gamut between old and new, as well as traditional and contemporary. We felt like this gave us more latitude to try something different without upsetting the overall look of the neighborhood.

With a smaller structure and only two basic rooflines, we knew any experimentation or design risk was going to have to occur at the level of siding materials and their orientation.

Knowing its weaknesses, I never imagined using wood for any part of the exterior of my house should the day come when I could build my own home. Brick, stone, metal, any number of man-made products (e.g. PVC or Boral), all seemed like the smarter way to go to avoid maintenance headaches and costly repairs. I assumed we’d end up using Hardie plank siding, or one of its paneling configurations, or maybe even some kind of metal product.

But then I came across charred cedar, or shou sugi ban.

It’s hard to remember now exactly where I saw it for the first time but I think it was a Dwell magazine profile of Terunobu Fujimori’s work. I may have even first seen the same architect featured in Philip Jodidio’s book Architecture Now! (HOUSES, volume 1). Regardless, once seen, it was hard to forget.

When we first began working with our initial builder, Evolutionary Home Builders, I brought them some rudimentary drawings I had done, expressing our desire to try something creative and out of the ordinary, especially in terms of siding layout.

Instead, their architect, Patrick Danaher, came back with an extremely conservative layout, one that’s fairly omnipresent when looking at single story ranch houses in the Chicago area.

Our use of charred cedar would have been the one change from what is typically a combination of brick or stone on the bottom two thirds of a wall with painted or stained wood up above, usually with a limestone ledge in-between to visually and physically separate the two materials.

Although attractive, I couldn’t help but feel that this layout was a cliched repeat of what’s already been done countless times before, which, nevertheless, would’ve been entirely appropriate had we been asking for a more traditional look. Eventually I realized there was no reason not to try something bolder and more thoughtful. I put together a fairly large sample board, mixing the charred cedar with natural cedar mostly in accordance with their initial suggested layout.

The sample board, although attractive, confirmed a couple of things I was worried about. First, the layout was way too traditional looking, even with the charred cedar. Second, this amount of natural cedar around the house would be a pain to maintain over the years, costing me significant time and energy, if not money (the maintenance labor would be DIY), probably requiring a fresh coat of tung oil at least every other year, if not annually. Since we wanted a natural look, any kind of traditional spar varnish, or other shiny clear-coat, didn’t seem appropriate. Although one option, open to us even now, is to just let the tung oil break down and let the natural boards turn gray over time (although it can be a somewhat unpredictable process).

Finally, since we felt the charred wood next to the natural was visually so electric, I thought it best to limit the combination to try and heighten the effect.

Installing the charred cedar

With all of the components of our wall assembly in place, Wojtek and Mark finally started installing the charred cedar on the house, beginning with the garage. This easily was one of the most exciting moments of the build.

I think Wojtek and Mark were secretly excited, too, if only because they were finally finished with all of the insulation and layers of strapping. It was more than a little exciting to see the first pieces going up, especially considering how far off-track our project had gotten early on.

With no choice but to have the garage thrust forward and so prominent on our front elevation, we just had to make the best of the situation. One way of addressing it was to shake up the orientation of the charred cedar. Since the siding on the house itself was going to be all vertical (we just find it more interesting), it made sense to change the north and south sides of the garage to horizontal.

In doing so, on the south side by the front porch this horizontal orientation would draw in the viewer’s attention, hopefully pointing it towards the front door of the house. Even as you walk up the front steps, this horizontal orientation, I would argue, does its subtle magic fairly well. At the street, or out in the front yard, this effect seems to work even better (have a look at the photo at the top of this column).

In mixing the siding’s orientation in this way it also helps to show what the material can do visually. Lastly, having these two sides of the garage oriented horizontally should also emphasize that this portion of the structure serves a different function (garage vs. house).

In keeping with our Urban Rustic aesthetic, the charred cedar—which would look just as good on a farmhouse or outbuilding as it would on an early 20th century artisan workshop or small factory warehouse—also represents our desire to bring in elements that reflect the Japanese notion of wabi-sabi.

Stressing the wood with fire instantly gives it an aged appearance, and the amount of variation also makes clear it’s a natural material, as opposed to an industrial product manufactured to meet narrow and precise tolerances. Whether it’s the knots, the lighter or heavier areas of char, some areas of natural cedar peeking through, or the oil stain marks, the charred cedar emphasizes and celebrates imperfections and inconsistencies in the wood.

Soffits and air vents

For the soffits, we were initially going to use a Cor-A-Vent product, PS-400 Strip Vent, to complete our cold roof assemblies, which included a ridge vent. But after opening the box and really taking a look at the strips, they just seemed really flimsy. I’m sure they would work fine, but holding them in your hand doesn’t exactly breed confidence. Also, seeing Wojtek’s stink face as he carefully studied a couple of pieces only confirmed that we needed another option.

After looking around online, I ended up finding a product at a local Home Depot—Kwikmesh galvanized mesh from Construction Metals, Inc. Not only did the metal mesh appear more substantial, I thought it would look better with the charred cedar than the PS-400, making for a nice contrast with the wood.

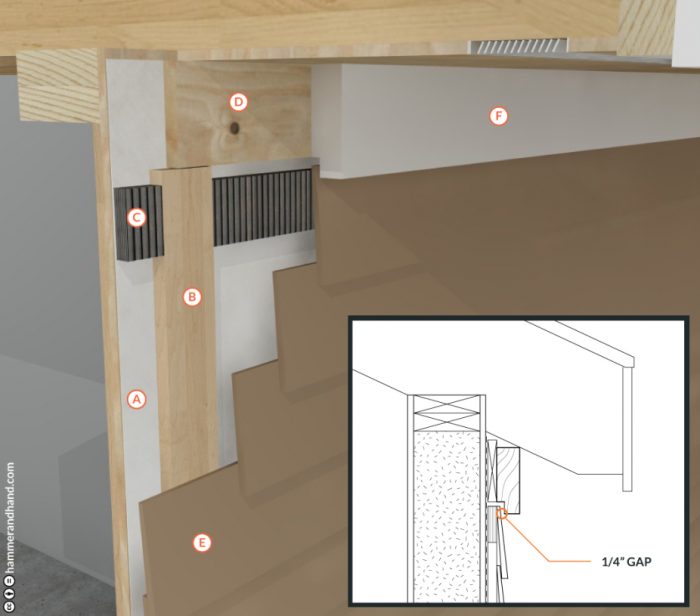

We were going to copy a Hammer and Hand diagram for the top of a wall, in particular their rainscreen detail for the frieze board.

After talking through the details, Wojtek and Mark found the notch in the frieze board to be an overly fussy detail. They preferred keeping this piece fully intact. To do this, they ripped down 2×2 furring strips to a thickness they could use as blocking behind the frieze board, pushing the frieze board out just beyond the plane of the siding to leave a roughly 1/4-inch continuous gap.

Apart from slightly more room directly above the Cor-A-Vent strip, the end result is much the same—a small gap between the frieze board and the top piece of tongue and groove siding allows air behind the siding to flow freely up and out of the wall assembly through the top of the Cor-A-Vent strips.

The Cor-A-Vent strips are kept about 1/4 inch below the initial blocking directly above them.

On the north side of the house I wanted to keep the charred cedar a monolithic black. The only real relief from this was the change in orientation of the siding from the north side of the garage to the house, along with a single window for my daughter’s bedroom. Knowing that the other three sides of the house would be getting some natural cedar accents, I thought keeping at least one side of the house entirely black would make for a nice overall effect.

Installing natural cedar accents

The west side of the house would be the first opportunity to use some of the natural accents. Based on my initial drawings and the sample board, I wanted to limit the natural wood as much as possible while still allowing it to have a strong visual punch.

I wanted to take advantage of the drop-off in grade in the backyard by using the natural boards around the window on the left. In doing so, it would draw attention to the change in grade, emphasizing that the left side of the west facade is significantly taller than the right side.

Using the structure of the window itself as a guide would help me to decide exactly how many natural boards to use. In addition, I knew I wanted a more informal look, making it consistent with our Urban Rustic and wabi-sabi design goals. Using an odd number of boards in an asymmetrical way would help achieve this.

By going just past the first piece of glass, the natural boards have a nice asymmetrical look to them—hugging or slightly wrapping around the window just enough, making a connection, but not too much.

After so many months of planning, worrying, and waiting—and then finally getting to see this combination of charred cedar with the natural cedar—watching the siding go up was easily one of the most gratifying parts of the entire build.

On most houses the back side tends to be rather boring, as if it were mostly forgotten about (at least in visual terms). In part this is no doubt because the details used to create visual interest are normally reserved for the front elevation where they can show off to the street. Where the front might be covered with stone accents, metalwork, elaborate lighting fixtures, or some other decorative accents, the other three sides tend to blend together as the basic siding material just continues its standard layout or pattern around the perimeter of the house. These decorative accents add cost to a build, so it makes some sense to reserve them for the side of the house that most people will see.

Sometimes, however, this effect can be jarring. A lack of cohesiveness can lend a kind of sadness to a house, as if it announces that the elaborate plans for the exterior cladding were ruined by unexpected budget constraints.

Consequently, we felt it was important to give each side of the house its own distinctive face. Because of the size and layout of our lot, and the way the houses next to us are positioned, it’s difficult to view more than one side of our home at any one time, which only encouraged us to make this a priority.

The effect of the natural cedar is also reminiscent of racing stripes, especially those seen on sports cars or muscle cars, or even motorcycles (e.g. the graphics on racing sportbikes). This was partly done with tongue planted firmly in cheek—if high-performance cars and motorcycles look good with racing stripes why not on a high-performance home?—but mainly because I’ve always enjoyed the visual power of these types of graphics.

For the south side, we decided to use the kitchen door as our guide for putting up the natural cedar, while the front door would be used on the east-facing facade.

Another element around the two doors to consider was exterior lighting. A single fixture at each door would project an upward and downward concentrated beam of light, highlighting the natural boards in the dark as they pinpoint their focus on this band of natural wood surrounded by total blackness. We started the natural boards to the right of center of the door’s glass, cheating a bit so that they started pretty much directly above the door handle.

We ended up at five boards for this side of the house, allowing the striping to stay proportional to the size of the opening while sitting just beyond the eventual light fixture. It also helps that the kitchen door, made up largely of glass and a neutral gray color, doesn’t take any attention away from the natural boards.

At the front door, I initially pictured the natural boards installed on the right side of the entryway. In two dimensional drawings this seemed to make sense, but after seeing everything in place in reality, it became pretty clear that to the left of the front door would be far better. To the right of the front door the natural boards would have seemed squeezed.

Many thanks to Wojtek and Mark for their patience in playing along as I figured out exactly how many natural boards to use, and exactly where they should be positioned.

Sill pans, gutters and downspouts

When most of the siding and overhangs were complete, Wojtek and Mark started installing the metal sill pans for all the windows and doors.

In the photo below you can see the horizontal layer of 1×4 strapping, which becomes a nailing surface for the 1×6 cedar board that will be used as a return back to the window frame.

We were going for a frameless look for the windows; meaning, once all the trim was installed, very little of the window frame is left exposed.

For the gutters and downspouts we went with Nordic Steel. They’re expensive, but they’ve lived up to the marketing claims: with a larger half-round gutter and wide diameter downspout, we’ve never had to clean out our gutters (so far, anyway). They also look really nice, and they fit in well with the Urban Rustic feel we’re going for.

How durable is charred siding?

Initially at least, our luck hasn’t been great with the charred cedar.

During our first summer with the siding last year we noticed that we had some carpenter bees buzzing around the house. At first, I didn’t think much of it since the charred cedar is supposed to be insect-resistant. But then I noticed a bee digging a hole above one of the windows and realized something needed to be done.

After reading up on their lifecycle, I used a spray inside the holes that were present (about 10 total after I went looking), following up a couple of days later with a few puffs of diatomaceous earth. After waiting two more days, I then stuffed each hole with some steel wool before covering each entry point with some black sealant. Once patched, these areas are virtually invisible.

After the siding had been up for about a year, especially after its first summer, it started to show some wear. Since the north side has held up the best, I can only assume it’s exposure to the sun that caused most of the wear to occur on the other three sides of the house and garage (although I’m sure rain played its part, too).

In general, areas with a heavier layer of char have held up better, but sometimes even in these areas we’ve seen some missing char develop.

Although the charred wood wasn’t in any immediate danger, and I enjoyed this aged look, my wife said she preferred the original, more opaque, black look of the siding. And to be honest, since many of these exposed areas were turning gray, I worried about how well any product we might try in the future would soak in and adhere, so I decided to address it this year rather than wait any longer.

Thankfully, I was aware of Kent’s blog, Blue Heron Ecohaus, having seen it featured on GBA. He goes into detail regarding his decision to use Auson black pine tar instead of a shou sugi ban finish.

Our siding was installed in the fall of 2017, and last summer I experimented with the recommended 50/50 mix of Auson and linseed oil, using it to touch-up a handful of boards, including all the cut edges that Wojtek and Mark had meticulously burned. Without any tung oil, these exposed edges had faded badly, almost to the same consistent gray on every piece. Again, this may be because they didn’t receive an especially heavy level of char when burned, but I can’t know for sure.

Even though the charred wood is said to easily last for decades, we also knew that it should get oiled about every 15 years to improve its durability, so having to do touch-ups wasn’t as heartbreaking as it might otherwise have been. I guess our 15-year mark came early.

If I was going to do charred cedar, or shou sugi ban, again—at this point, that’s a big if—I would insist on doing a uniformly heavy char finish (or ‘gator’ finish), and I would use the black pine tar to try and seal-in the char as much as possible. As beautiful as the lighter charred areas were when they first went up, they just couldn’t stand up to the weather.

Nevertheless, the pieces of shou sugi ban that we’ve incorporated into our interior have held up nicely with just a tung oil finish, showing no signs of deteriorating, presumably because they’ve avoided any direct sun or rain (more on these areas in a future post).

So even with all the time, effort, money, and frustration that’s gone into making the charred cedar work, I still love the way it looks every time I pull into the driveway, or notice it while working in the yard. It’s just important to understand that as with anything worth doing, or any labor of love—like building our house, it could be said—it comes at a price.

Other posts by Eric Whetzel

- Exterior Insulation and a Rainscreen

- The Blower Door Test

- Choosing and Installing a Ductless Minisplit

- Installing an ERV

- Choosing Windows

- Attic Insulation

- Installing an Airtight Attic Hatch

- Air Sealing the Exterior Sheathing

- Installing a Solar Electric System

- Prepping for a Basement Slab

- Building a Service Core

- Air Sealing the Attic Floor

- Ventilation Baffles

- Up on the Roof

- A Light Down Below

- Kneewalls, Subfloor and Exterior Walls

- Let the Framing Begin

- Details for an Insulated Foundation

- The Cedar Siding is Here — Let’s Burn It

- An Introduction to a New Passive House Project

Weekly Newsletter

Get building science and energy efficiency advice, plus special offers, in your inbox.

23 Comments

We've been thinking also of doing Shou Sugi Ban for our addition on Martha's Vineyard. Needless to say the condition of the boards on the west side of Eric's house after just two years left me shocked how horrible it looked and questioning whether to proceed with Shou Sugi Ban. We've been working with Bill Beleck at Nakamoto Forestry https://nakamotoforestry.com as the supplier of authentic Shou Sugi Ban siding for our project. I contacted him for his take on the result. Here is what he said:

“….yes we actually see this a lot and it’s a headwind for us. That house looks horrible and our product gets judged on stuff like this It all starts with “sugi” being translated as “cedar” instead of “cypress”. There are two cypresses in Japan, Hinoki and Sugi, and over the last 150 years their names have been translated opposite of what they should have been. Hinoki is translated as cypress but can’t be used for yakisugi, Sugi is the only species we’ve had good result with and is translated as cedar, but is actually close in grain character to southern bald cypress. Therefore people think it is OK to burn cedar when in reality the red, yellow, and white cedars all have paper-thin, non-structural latewood growth rings which means that they do not hold a protective soot layer for very long as sugi does. Also people here are lightly burning the wood and you have to burn it beyond your threshold of logic, to where you think the wood is ruined."

While I understand the DIY ethos of many readers on this site, given the time involved and uncertain results, it's often better in the long run to purchase a finished product made by professionals.

“[Deleted]”

I think it's worth also looking at Nakamoto Forestry's historic photos and discussion of durability. I think folks often think that Yakisugi/Shou Sugi Ban will look solid black forever, and that doesn't seem to be the case, at least based on Nakamoto Forestry's photos of Japanese buildings using it. That said, they're discussing the natural degradation of the material over decades, not years, so that's definitely a big difference.

Historic Gallery: https://nakamotoforestry.com/what-is-shou-sugi-ban-yakisugi/

Durability: https://nakamotoforestry.com/yakisugi-shou-sugi-ban-80-year-siding-longevity-truth-or-rubbish/

From the durability page:

"Yakisugi is rarely maintained in Japan, and what I’ve seen is that the yakisugi planks get thinner and thinner over the decades from UV degradation. Nails will get more proud of the surface as the wood surface erodes. Once the boards get too thin, the planks start to split. This takes 80~150 years depending on plank thickness and wall orientation. Siding in Japan is standard 10~15mm thick, and a 10mm plank installed facing south or southwest orientation will wear through and start to split, exposing the substrate, in about 80 years. So what I’ve seen in Japan is that UV degradation is the defining factor in yakisugi longevity since they traditionally rarely do re-oiling maintenance. You can learn more about yakisugi and see photos from Japan in our Historical gallery here."

Brendan,

Good points. I have had two clients suggest we use Shou Shugi Ban on their houses. I'm pretty sure both were motivated by the desire for black cladding , which is all the rage in architectural periodicals and sites like Houz right now. Shou Shugi just provided a cool backstory to justify it. Once I pointed out that it would not maintain the favoured dark colour without periodic maintenance, one opted for paint instead - something that pleased me as I hope they get a more sympathetic colour scheme in the future. The other client now has a mainly orange tiny-home.

There are lots of good reasons why so many MV houses have untreated white cedar shingles. They don't need maintenance. They are made from a renewable resource. They look nice.

Long after charred cedar siding looks as dated as Palladian windows, white cedar shingles will still be a great choice in New England.

Thanks Stephen....I'm well aware of white cedar shingles....the shingles on the original house are now 37 years old and going strong, and I've designed at least a dozen houses on the Vineyard all with white cedar shingles.....but for this addition to my own home, I'm looking for a variety of ways for it "not to blend in" but to stand out as a somewhat modernist artifact. Horizontal board rainscreen for sure, and probably, but not necessarily, Shou Shugi Ban.

Another option I link to on my blog worth considering is a metal product made to look like charred cedar:

https://www.bridgersteel.com/metal-colors/charred-wood

I'm sure it's not cheap, but maybe worth getting a sample and a price quote.

Of the companies we looked at back in 2015-16 before deciding to do the charring ourselves --- charredwood.com, Delta Millworks, reSawn Timber --- only the latter, as far as I can tell, goes into some detail regarding the aging process and the need for periodic maintenance. If I was to order shou sugi ban from any of these companies, I would request photos of installations that have been in place for at least a few years, and ask if I could speak with the homeowners about the material to see how it's holding up.

When we decided to use the shou sugi ban there wasn't much info online about projects that had been in place for awhile. All we had to go on was its stated reputation for long-term durability, and recently completed projects that, of course, looked pristine.

Since its popularity has grown in the last few years, woodworkers have also taken on shou sugi ban and come up with some really interesting twists on what was a fairly humble and traditional exterior cladding. Worth considering if any woodworkers here on GBA are looking to try something new and unique for an interior finish. Pinterest and other sites show an incredible range of design choices available. Also an option for homeowners who love the look of shou sugi ban but don't want to deal with any exterior maintenance issues.

I learned - very quickly - on a dining table project that unless your wood is very dry indeed, heating it rapidly on one side can lead to pretty intense cupping. Whatever approach you take, do test your materials, torch and spreader, burn depth, etc. very carefully before committing to a large project.

Many building products, especially outdoor products, are very climate specific. What might work in the Pacific NW, can turn into a disaster in the Desert SW. I can say for sure that exterior wood products in the Desert SW states like Arizona DO NOT do well. The intense UV and heat does a number on exposed wood. Cupping, splitting, warping, sun burning, insect infestations, twisting, etc. is what happens to exposed wood out here. Synthetic stucco and metal are your friends in the Desert SW.

Putting linseed oil on the exterior planking is a disaster waiting to happen in certain climates. Linseed oil can spontaneously combust & catch fire with no outside spark at just 120F. That's the average summer temp while in direct sunlight in desert climates.

Not sure about the climate in Japan and how many days of sunlight it gets. What works in Japan might not work in the USA. Buyer beware!

It is my understanding that linseed oil is food for the mildew etc

One of the attractions of cedar is the lack of maintenance.

My last house was VG cedar clapboard, which needed nothing, while I never took the ladder down from painting the trim. New owners promptly painted the siding.

Shrug.

Many woods, as long as they drain, will last for a very , very long time.

Is the charring intended to create a more durable finish? If so, why would charring accomplish that goal? It seems to me that the charred layer would be less durable than uncharred wood. One major threat to siding is U.V. light from the sun. I could imagine that the charred layer might offer U.V. protection. Is this charred siding typically oiled with linseed oil?

The last house I built had 1 X 8 redwood T&G siding. This was face grain with a mix of heart and sap wood. It looked gorgeous when I put it up, and I did not want to paint it. So I sought to experiment with boiled linseed oil with the thought of re-applying it every few years. The new redwood freshly oiled was breathtaking. But none of this lasts.

I applied the first coat with a large garden sprayer very wet and generous. The point was to get the wood to soak up as much oil as possible on the first coat because I wanted to get it to penetrate as deeply as possible. Then the oil sets up solid within the wood. Subsequent oil applications will not penetrate deeper than the first one because solidified oil nearest the surface prevents new wet oil from being drawn into the wood.

The wet look of the oil is very rich, but only lasts for 3-6 years, and then there is no indication that any oil is present. But, the oil has soaked into the wood and is evident there; if for instance, one tries to sand the wood, then it instantly plugs up the sandpaper. So the oil has deeply penetrated the wood and will provide good protection to prevent the wood from soaking up rain water, swelling, and then shrinking as the sun dries it back out.

However, the oil offers no protection against UV, which burns away the wood over time, leaving deep relief between the early wood and late wood figuring. Aesthetically, that looks nice, but wood is being lost to the UV erosion and the board gets thinner over time.

In subsequent oilings, at several-year intervals, I used a large nap roller on a pole, and rolled the oil two stories up the siding. I built a catch basin along the bottom of the siding to catch the considerable runoff, and they re-rolled that up the siding. Intermittently, I used a scrub brush on a pole to scrub the wet oiled siding for improved penetration.

I believe the idea is that it's not just the layer of char that protects the wood, but the heat treatment process itself: https://nakamotoforestry.com/what-is-shou-sugi-ban-yakisugi/

My impression from the above article is that the wood is traditionally not oiled, but if you want to make the initial aesthetic last longer and not patina as fast, you can oil it.

I find Eric's blog really refreshing. He doesn't shy away from describing mistakes, or things he might do differently another time - and he has ended up with a well performing, very nice house.

Agreed!

Thanks Malcolm and Brian! I genuinely appreciate it.

GBA was such an invaluable resource and inspiration for our own build, so it's nice to think my blog may be helping others complete their own projects --- even if it's just avoiding some of my mistakes :)

Good day Eric! Such an excellent article with creative tips. I am so thankful for you and your blog about Urban Rustic: Charred Cedar Siding. Thanks for sharing such an informative post with us. I was searching for this type of blog every day and your blog is very helpful for us. Keep posting such an amazing post. It was a great experience here.

https://www.cedarinnovation.co.nz/

Eric,

I hope this finds you and your family well during this difficult time.

Thank you for all of your wonderfully helpful blog posts! We love the look of black cedar siding as well. Originally we were planning on charring it, however after seeing how yours held up we have second thoughts.

Given you had to touch it up with the pine tar -- if starting from scratch, would you consider going with only black pine tar? What would the pros/cons be of that?

Thank you!

curiousgreenzebra,

Thanks for the kind words!

The pine tar is a traditional Scandinavian finish, so it should hold up well on its own. Of course, even though it's black, you would be giving up the alligator-like skin of a heavy char finish. In terms of durability, it might be 10-15 years before you have to recoat it, but of course that's going to be dependent on location I'm sure (e.g. Phoenix vs. Maine or even Seattle), and its exposure to direct sun. They also recommend 2-coats (if memory serves) for brand new untreated wood.

If we had it to do over, instead of dunking the charred pieces in a tung oil bath we would've tried using the pine tar. Most of our pine tar touch-ups are only one year old, so even though they look good so far it's hard to reach any conclusions about long-term durability. If we can get close to 10 years before having to do more touch-ups, I'd be happy recommending the pine tar. My guess is the mix of charred wood with a tinted finish like the pine tar is probably the best way to go to maximize the durability of the finish --- but, at this point, it's only a guess.

We still love the look of the charred wood --- it's variation in texture, and the instantly aged look --- but it's clearly not to everyone's taste (especially if going for a brand new, pristine look).

If using a company that will char for you --- Delta Millworks, charredwood.com, ReSawn Timber co., or, as Hugh suggests, Nakomoto --- I would ask to see some photos of homes where the siding has been up for at least 5 years to give you a better sense of what the finish will look like over time. If you can speak to a homeowner about the material, even better.

In terms of cost --- DIY or using one of these companies --- it's going to be more expensive than other finishes (your money or your time, or both). Although, if you love the look, as we do, it is hard to beat in visual terms.

When I first heard about Thermory and their Shou Sugi Ban option (https://www.thermoryusa.com/rebel-series-ignite/), it sounded bullet proof although pricey, but I've since heard that cut ends require treatment, as well as any damage to the face, so it's not perfect either. I don't think it's been around for very long yet, so using it isn't risk free either --- time will tell if the durability claims are accurate.

Truth is, no matter what cladding you choose, no matter how durable, it can be undermined by a poor installation. Something to look out for whether you're installing it yourself, or hiring someone else to do it for you.

Eric,

Thanks a lot for your thoughts! It will probably a couple months yet until we have pictures to share but I will post them and let you know what we decide.

As mentioned earlier, we were working with Bill Beleck at Nakamoto Forestry https://nakamotoforestry.com as the supplier of authentic Shou Sugi Ban siding for our project. We ended up using their Gendai version, where some of the char is brushed off....what can we say, they provided us with a fantastic product that was shipped carefully in a crate with spacing between pairs of boards...everything arrived on Martha's Vineyard in perfect shape. And while we're still not finished with the project due to delays caused by COVID19, we love the end result....we sized windows and doors to fit the board dimensions and our carpenter came through to work everything out perfectly. Here's a couple of in progress photos.

Hugh,

Wow looks beautiful! That seems like an expensive option for us but if its in the budget that clearly seems the way to go.

Actual cost of siding is $6.50 per actual square feet of coverage. Other, than slapping on some stain at cut ends, there are no other finishing costs.

There are now two houses with Shou Sugi Ban cladding within a few miles of me, both which are under three years old. One has turned mainly orange, the other just looks like weathered cedar.

I know there are methods to prevent this, but it seems like a logical disconnect to use a technique that originated to preserve wood, then have to apply frequent coating to preserve the look of it.

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in