Image Credit: All photos: Andrew Dey

Image Credit: All photos: Andrew Dey Flachau's wood-chip boilers are housed in this industrial building with steel cladding. The hot-water distribution pipes can be seen in a few locations. This is where one of the pipes crosses a river. I saw four jars of different types of chips on top of what looked like a laboratory oven. Christian said, “When a truck shows up with a load of chips, we weigh it there, and we take samples of the chips. The truck is then unloaded and weighed again. We dry the chip samples in this oven to determine the moisture content. We pay for the load of chips based on the weight and the moisture content — the lower the moisture content, the more valuable the chips.” We walked out into the yard behind the facility. The logs stacked high near the building would be ground into chips on site. The piles of what looked like steaming chopped pine needles and bark had been chipped in the forest, and delivered by container truck. Christian explained that although the heating system is designed to burn a wide range of materials well, they often mix the forest waste material with wood chips to improve the quality of the burn. Christian led me to the side of the building where we stood between two large, covered bunkers full of chips. Steam rose from the piles of chips, and the air smelled of spruce. Hydraulic rams push the chips into chutes that lead to the burn chambers of the two boilers. The chips are fed into rear of the combustion chamber. Inside the building, all the action was taking place behind the walls of large containers. The burn chambers are massive boxes. They are connected to large vertical cylinders — the heat exchangers — where heat from the burning chips is transferred to water being pumped through. The photo shows the 3 MW boiler with its heat exchanger. This is the 5 MW boiler. An impressive array of pumps pushes the water out to the town buildings and back. After the heat has been transferred to the water, most of the focus of the system is on the flue gases. The gases are ducted through a multicyclone filter to remove relatively large particles. The gases then travel through an electrostatic filter (shown in this photo) to remove the finer particles. Following the filters, the flue gases enter an exhaust gas condenser (shown in the photo) that removes much of the latent heat. The heat from the gases is transferred to water, and fed back into the heating system. Christian led me into an adjacent room that was mostly taken up by a large apparatus that looked like it might involve cooling. “This is a heat pump,” Christian told me, “that removes additional heat from the flue gases. The heat is reused, and the cooled flue gases are sent up the chimney. This particular heat pump is one of the first of its kind to be installed in Austria.” We exited the building and walked past blue plastic chemical containers (“to neutralize the condensate”) and the dumpster into which ash was deposited.

Annette, our daughters and I just spent a week in Flachau, Austria, with Annette’s family. Flachau is not far from the Austrian city of Graz, where Annette lived until she was twelve years old. Thirty years ago, Flachau was a sleepy farming village, and today it’s a bustling ski town.

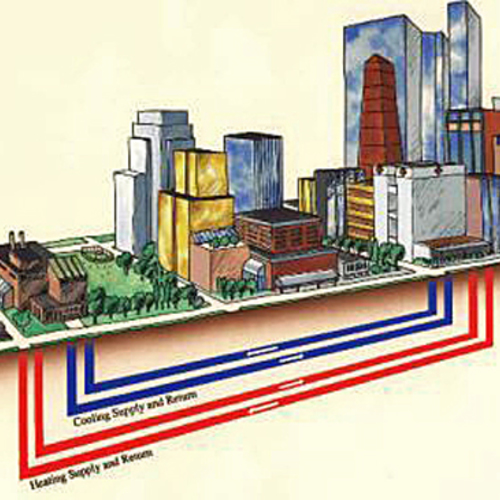

One morning, Annette and I were pulling our two-year-old nephew Jonas in a sled along a cross-country ski trail that brought us by a large industrial building flanked by huge piles of logs and chips. “Holzwärme Flachau,” read the sign on the front of the building — “Wood Heating Flachau.” The building is the heart of Flachau’s “Fernwärme Netzwerk,” or district heating system. Locally sourced wood chips are burned to create hot water that is pumped throughout the village to provide heat and hot water to residents.

A few days later, I was back at the facility, asking for a tour. I walked into a modern, comfortable office where I found two men at work. On one wall hung a schematic diagram of the heating plant. On another wall was a large sheet of charts and graphs representing various aspects of the heating system over time. I explained to the two men my interest in renewable energy systems, and they answered my questions patiently.

When was the facility built?

The larger of the two boilers was installed in 2007. The smaller boiler came online in 2009.

What’s the capacity of the system?

The facility runs two chip-fired boilers, one with a capacity of 5,000 KW (5 MW), and the other with a capacity of 3,000 KW (3 MW), for a maximum output of 8,000 KW (8 MW). During the winter, both systems are used, but in the summer, generally just the smaller one is needed. Having two systems in parallel facilitates maintenance and cleaning — work that is scheduled for the summer months. The system includes a back-up oil-fired boiler with a capacity of 10 MW.

When is the back-up system used?

Only in an emergency, when the other systems are not working. In other words, basically not at all.

How many buildings are served by the district heating network?

All of the buildings in the village of Flachau, about 400 total — including a number of hotels with heated swimming pools. As new buildings are built, they are connected to the system.

How many kilometers of buried pipe bring the heated water to the buildings and back?

About 24 kilometers.

What’s the pipe diameter, and how is it insulated?

The pipe diameter varies depending on where the pipe is located in the system, and on the needs of the particular buildings being served. The pipes leaving the facility are 200 mm (about 8 inches) in diameter. The smallest pipes in the system are about 25 mm (1 inches) in diameter. The pipes are insulated with rigid foam that is about 7 cm (3 inches) thick.

What percentage of heat is lost due to conduction from the piping system?

The heat loss depends on many factors, but it averages between 16 and 18% annually.

Was it difficult to install the piping system?

Yes [said with a smile]. Especially because the large insulated pipes for district heating had to be fit around the elaborate existing underground system of pipes and wires. [From the few pipes that I saw adjacent to bridges in town, it appeared that the pipes were buried only about a foot below the surface, not below frost level.]

Does the system provide both heat and domestic hot water, or just heat?

Both. The piping system consists of two loops: one supply and one return. A single supply pipe of hot water enters each house. In the house, a heat exchanger is used to separate the hot water for heating from the domestic hot water for sinks, showers, etc. A single return pipe exits each house.

Why was a chip boiler chosen, instead of a pellet boiler?

Chips can easily be produced locally — in the forest from logging waste, or at the facility using low-grade logs. Pellet production is an energy-intensive activity that would have required its own plant.

Where do the chips come from that fuel the system?

From local forests, all within a 30 to 40 kilometer radius.

Wood species?

It doesn’t really matter, because this particular system is designed to burn a wide range of fuels, including low-quality mixtures containing a high percentage of needles and bark. Most of the wood happens to be spruce, because that’s the most common species in the area.

Was a cogeneration [heat and electricity] plant also considered originally, rather than just a heating plant?

Yes, but they are technically more challenging, and the added benefits were not deemed to be worth the additional cost and complexity. Also, about 60% of the electricity produced in Austria already comes from renewably sourced hydropower.

How many people are employed to operate the system?

Three people work at the plant and maintain the system, but the plant also helps to ensure jobs in the local forestry industry.

How much did the entire system cost to install?

About €13 million [roughly $18 million, or $45,000 per heated building].

Who paid for the system?

The system is owned by a cooperative [Genossenschaft]. The cost was financed by a local bank. Installation of the system was overseen by SWH (Strom und Wärme aus Holz, or Power and Heat from Wood), an offshoot of Austria’s national forest agency with the mission to promote biomass-based energy production.

Building owners in Flachau pay for the heat and hot water they use on a monthly basis. These monthly bills are significantly less than they would be if the buildings were using oil, natural gas, or electricity for the heat and hot water.

Are there many such systems in Austria?

In the Austrian state of Salzburg where Flachau is located, there are over one hundred such installations; nearly every town has one. The number of installations in the state of Upper Austria is even higher.

The systems are popular for many reasons. Because most of the systems are locally owned and the fuel comes from nearby forests, money remains in the local economy. The systems are essentially CO2 neutral. The system in Flachau saves the equivalent of 3 million liters [nearly 800,000 gallons] of fuel oil each year.

Has the system been operating well? Any particular challenges or surprises?

The system has been working well, and the townspeople have been very happy with it. The owners of local hotels and guest houses are particularly enthusiastic, because the district heating system helps to protect their businesses against rising energy prices.

The system is technically complex, and has many sophisticated components that require monitoring and care. The multi-cyclone filter is one such component. The electrostatic filter is another. The condensation system that recovers heat from flue gases is a third.

Austria is making impressive strides in the area of renewable energy. Germany has also made rapid progress, but it seems that Germans are starting to question the costs. Do you see similar pushback in Austria?

Austria’s efforts at implementing renewable energy and energy efficiency have been steady for years, a process of continual improvement. In comparison, Germany’s ambitious Energiewende has resulted in more rapid progress, but perhaps it is not as sustainable. Austrians are generally very supportive of renewable energy, particularly when it can be locally produced and used.

A tour of the facility

Following my “Twenty Questions,” one of the men — Christian Jäger — gave me a tour of the facility. The photos and captions below explain what I saw during my tour.

At the end of the tour, we exited the building and walked past an array of blue plastic chemical containers (“to neutralize the condensate”) and the dumpster into which ash was deposited.

Christian pointed to a multistory addition that was still under construction on the far side of the building. “That addition is for a Pufferspeicher [buffer tank]. Because we have many hotels in Flachau, there tend to be spikes and large fluctuations in the demand for heat and hot water. The buffer tank will allow our heating system to accommodate those fluctuations more efficiently.”

Christian and I headed back to the front-end loader in the yard. ”Time for me to start mixing chips,” he said. I thanked him for his time. “Bitte schön,” he said — “You’re welcome.” He smiled and added, “Considering that all we’re doing here is making hot water, it’s pretty complicated, eh?”

Andrew Dey’s background includes carpentry, contracting, and project management. For the past six years he has provided construction consulting services to clients in New Hampshire, Vermont, and Massachusetts. He is passionate about retrofitting existing buildings — including his own house — for greater energy efficiency. His blog is called Snapshots from Berlin.

Weekly Newsletter

Get building science and energy efficiency advice, plus special offers, in your inbox.

3 Comments

Question on sustainability

First, I wonder how many acres of forested land are needed to "sustain" a plant of that size. Given the large number of similar facilities in the region, do they compete for the same forested areas? I'm reminded of how the growth of London centuries ago, along with the use of wood for heating and cooking back then, resulted in the edges of the forests being pushed steadily further out as wood cutters took trees for fuel.

Next, if the trees weren't being harvested for fuel, over time they would return to the soil, naturally composted, to help continue the ability of the forest to sustain regrowth. To what extent does the use of the forest for fuel by such facilities impact the (very) long term health of the forest? Is this truly sustainable in all ways?

Response to Dick Russell

Dick,

The Austrian government has a policy to ensure that forestry practices in Austria are sustainable. Laws regulating logging in Austria are far stricter than those in the U.S. For more information, see:

http://www.fao.org/docrep/w3722e/w3722e05.htm

http://www.oeaw.ac.at/forebiom/WS1lectures/SessionI_Englisch.pdf

http://www.eficent.efi.int/files/attachments/eficent/projects/austria.pdf

One more thing to remember: although it may be impossible to quantify all the effects of logging and wood chip use, the Austrian approach to sustainable forestry and the use of wood chips is much closer to being carbon neutral than the main alternative (burning fossil fuels). Since the burning of fossil fuels is rapidly changing our planet's climate, the Austrian example shouldn't be casually dismissed.

Sustainability of biomass...

Martin,

I agree but I also think Dick is right to be skeptical or have concerns about biomass combustion at these scales in the long term.

Even where current policies are effective at "ensuring" a sustainable forestry industry, there is nothing to guarantee that future circumstances won't undermine that policy.

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in