Gas stoves are a leading source of hazardous indoor air pollution, but they emit only a tiny share of the greenhouse gases that warm the climate. Why, then, have they assumed such a heated role in climate politics?

This debate reignited on Jan. 9 when Richard Trumka Jr., a member of the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission, told Bloomberg News that the agency planned to consider regulating gas stoves due to concerns about their health effects. “Products that can’t be made safe can be banned,” he noted.

Politicians reacted with overheated outrage, putting gas stove ownership on a par with the right to bear arms and religious freedom. CPSC Chair Alexander Hoehn-Saric tried to douse the uproar, stating that he was “not looking to ban gas stoves” and that his agency “has no proceeding to do so.” Neither does the Biden administration support a ban, a White House spokesperson said.

Nevertheless, congressional Republicans raced to the barricades, introducing bills with titles like the Guard America’s Stoves (GAS) Act and the Stop Trying to Obsessively Vilify Energy (STOVE) Act.

This skirmish may seem like a tempest in a teapot, but it reveals important contours of the battlefield on which climate politics are waged. As I explain in my book, “Confronting Climate Gridlock: How Diplomacy, Technology, and Policy Can Unlock a Clean Energy Future,” gas stoves matter to climate and to the gas industry because they serve as gateway appliances to the dominant residential uses of natural gas: heating and hot water.

Serious health effects

Direct impacts from gas stoves are a much more urgent concern for human health than for Earth’s climate. Gas stoves are a leading indoor source of nitrogen dioxide, or NO₂, which can cause or worsen respiratory illnesses in people who are exposed to it.

For example, scientific studies show that living in a home with a gas stove increases children’s risk of asthma by nearly one-third and contributes to pulmonary disease in adults.

The climate doesn’t care what fuel we use to cook. Gas stoves account for just 0.1% of U.S. greenhouse gas emissions, even accounting for recent findings of larger than expected household methane leaks. They aren’t a big share of fuel sales either, burning just 3% of the natural gas consumed in homes.

Impeding home electrification

The significance of gas stoves for the climate becomes clearer in the context of the Biden administration’s goal of achieving net-zero U.S. greenhouse gas emissions by 2050. This target can only be achieved by curbing fossil fuel use across the economy, including in homes.

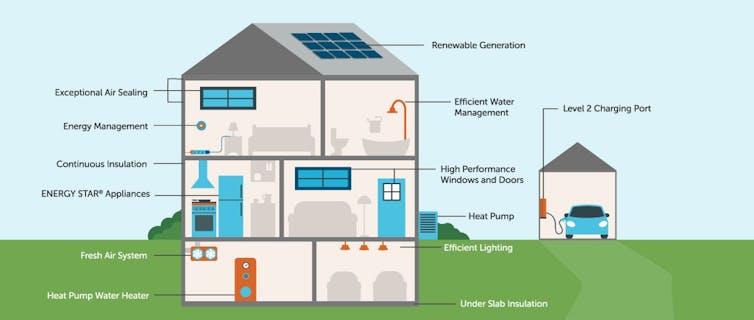

Installing more-efficient furnaces, better insulation and smart thermostats are helpful first steps, but getting close to zero will require switching to electricity for space heating and water heating. In the U.S., 46% of homes use natural gas as their main source of heat, 40% use electricity, 10% use other fuels such as heating oil or propane, and 4% are unheated. For water heating, the percentages are 47% gas, 47% electricity and 6% other fuels.

Today, electric and gas heating have similar carbon footprints, since roughly 60% of U.S. electricity is generated from fossil fuels and many homes use inefficient electric resistance heaters. But the emissions intensity of electricity is rapidly declining as coal plants close and solar and wind power expands.

President Joe Biden has set a goal of 100% clean electricity nationally by 2035. Although current federal policies fall short of that target, a growing number of states have committed to 100% clean electricity by 2050 or sooner.

Natural gas is far harder to decarbonize than electricity. Lower-carbon fuels such as biogas and hydrogen that could be blended in with natural gas are likely to remain scarce and costly.

Furthermore, advanced technologies enable electric heat pumps to heat both air and water far more efficiently than traditional electric or gas furnaces and water heaters. That’s why various scenarios for decarbonizing energy all envision a major shift to electric heat pumps. This transition is well underway in Europe and starting in the U.S.

Replacing existing gas furnaces and water heaters with electric heat pumps can be costly and complicated, though incentives from the Inflation Reduction Act can help. But if new homes are built fully electric from the start, they avoid the cost of installing natural gas hookups, and emit far less air pollution and fewer greenhouse gases throughout the homes’ lifetime.

New York City and more than 50 California towns, cities and counties have already banned gas hookups in new buildings. Elsewhere, 20 states have barred the enactment of natural gas bans.

Gas stoves are a big reason why.

The power of a slogan

“Most people don’t care how their water is heated or how their heater works, but the Viking stove in the kitchen, people have this visceral emotional attachment,” Michael Colvin of the Environmental Defense Fund told me in an interview for my book, “Confronting Climate Gridlock.”

That emotional attachment makes stoves a flashpoint in battles over climate policy.

“Cooking is the hill that the gas industry wants to fight on,” Bruce Nilles of Climate Imperative told me in a 2020 interview that foreshadowed the current skirmish. “They’ll say, ‘Do you want the government to take away your gas stove that makes you a great chef?’”

The American Gas Association has promoted the notion that gas stoves make skilled cooks since the 1930s, when it introduced the advertising slogan “Now you’re cooking with gas.” An AGA executive planted the phrase with writers for comedian Bob Hope. Soon it was picked up by comedian Jack Benny, and even by Daffy Duck. The phrase has also appeared over time in social media endorsements and hashtags.

Gas burners do provide more control than many stoves with electric coils, especially older models, which can be slow to heat up and cool down. Today, however, many chefs, consumers and experts say gas is no longer the obvious choice. Magnetic induction cooktops, which cook using electricity to generate a magnetic field, heat faster, control temperatures more precisely and use less energy than other stoves.

“There’s this big misconception that electric ranges don’t cook as well as gas,” Shanika Whitehurst, a member of Consumer Reports’ research and testing team, said in a recent article. “But the technology has improved to the point where electric and especially induction ranges and cooktops cook every bit as well, if not better than gas.” Consumer Reports ranks induction and some traditional electric stoves among its top-rated models.

Homes built today will endure far beyond Biden’s 2050 net-zero target. And the longer the gas-is-better myth persists, the harder it will be to fully electrify new homes from the start. As I see it, if “cooking with gas” keeps us tethering new homes to natural gas grids for decades to come, our health, climate and wallets will pay the price.

Daniel Cohan is an associate professor of civil and environmental engineering at Rice University. This post originally appeared at The Conversation.

Weekly Newsletter

Get building science and energy efficiency advice, plus special offers, in your inbox.

22 Comments

The main issue with gas stoves is linked to fire hazard. According to the National Fire Protection Agency (NFPA), kitchen fires are the first cause of residential fires (an average of 550 civilian deaths, 4,820 reported civilian fire injuries, and more than $1 billion in direct property damage per year).

See https://www.nfpa.org/News-and-Research/Data-research-and-tools/US-Fire-Problem/Home-Cooking-Fires

In gas stoves, open flames act as ignition source for flammable volatiles produced during cooking by grease, oil, etc. so the likelihood to start a fire is significantly higher than in electric and induction stoves (no open flame that can act as ignition).

These reasons by themselves might justify banning of gas stove in residential applications.

The front page of the link you provided says the opposite: "Households that use electric ranges have a higher risk of cooking fires and associated losses than those using gas ranges."

Good catch! An electric element can indeed act as ignition source if it reaches glowing temperature, especially with exposed elements. The numbers gas vs electric fires might be skewed by the fact that in USA electric is likely more popular than gas. Anyway, this is a reason more to forget about gas AND electric and go with induction stoves

I've successfully ignited oil in the bottom of a frying pan with an electric stove, without any contact between the oil and the coil, just by heating it up to the smoke point and beyond to where it burst into flame. (I got interrupted when had just turned the stove on high to warm up the pan, and I became engrossed in the interruption, and left the stove on high unattended.)

A great new invention that I don't think is on the market yet is pans for induction stoves that have a Curie point at a good cooking temperature. If you heat them by induction beyond that point, they become non-magnetic and the induction heating become vastly less effective. So this sets a maximum temperature that an induction burner can't heat them beyond. You could have a pan that would allow you to reach the smoke point of vegetable oil, but never light it on fire, so you can fry things at high temperature without the danger of the fire I lit. Or you could have a pan that is calibrated to go to the ideal temperature for cooking pancakes. You put the burner on high and it will go straight to the point and hold that temperature as long as it takes to make a stack of perfect pancakes.

This article is very alarmist about gas stoves/heating, and just seems to just be pushing a very "green agenda" without all the facts. If you properly vent your kitchen stove when cooking, then it will have very little effect on indoor air pollution. Let's not forget that having proper home ventilation by itself will go a long way to remove cooking pollution by itself.

Furthermore, when you cook food, you create pollution no matter what method of heating you use. Cooking is simply a controlled "burning" of your food, which contains all sorts of organic and inorganic chemicals. So the cooking smell itself, while delicious is also a pollutant. But this is glossed over in the "greenwashing" attempt to portray anything but electric based heating/cooking as bad.

Another thing that people forget/gloss over, is the dependability and backup potential of natural gas. Your home loses power, but you can still cook your food and have heated water if you have gas, and you can even have electricity and heat with a backup whole house gas generator(and it's relatively affordable, between $5K - 10K for an average house), unlike "green" energy.

With an all electric house, losing power means you can't live there at all. Yes, you can invest $50K to have a 15KW solar array, and a large battery backup system. But, who really can afford that? Certainly not the average person who lives in an all electric house.

We grew in a gas cooking/heating home, where my Mom baked and cooked extensively.

There was no hood venting either. It was a house that was built in the 1928, so there was good air exchange from outdoors (it was leaky).

Yet, none of us three children suffered any ill effects, and neither did my parents. We are all healthy, and parents are 82 and 94 right now. Contrasting to today's kids, we ate good whole food Mom prepared. Our screen time was limited, as there was only so many re-runs you wanted to watch, so we ran around outside and got exercise. As a result, we were healthy, as were the kids around us.

Some people live long lives with all kinds of air pollution that on average worsens and shortens lives. My father used to spend an evening or two a week sitting by a fireplace throwing on bits of burnable garbage, including all kinds of plastic. He also spent a lot of his life as a smoker. I'm not going to say those were good things for him to do, even if he did live to be quite old.

I think people should get air quality monitors first off, because they're good things to have anyway and not terribly expensive, and judge whether their range hoods are actually doing much of anything. Even a range hood that's fairly powerful and vented to the outside (lots are neither) isn't likely to be turned on for enough of the cooking time to make a huge difference, is my guess.

Induction ranges produce less cooking pollution in part because you're not constantly burning off old spills on the burner. If sauce or grease spatters, you can wipe it up just as if it had gone on the counter or the floor. When I look at the air quality monitor record, there is of course a spike when we cook dinner, but it goes away quite quickly. (It also makes a surprising amount of difference to clean out the toaster regularly. If there are a lot of old crumbs in the toaster, the "toaster spikes" are much higher.)

In 2020 about 26% of households in the US had electricity as the only source of energy (and there must be more households like ours where there's just one gas appliance left - we haven't yet replaced the water heater). Somehow I think something a quarter of us already do is, well, doable.

I don’t think we’re that far apart in our mindset, or in our points. I will say that my least favorite part of a gas stove is cleaning it, and all the inevitable splatters. Agree on the toaster, my nose is very sensitive, I can immediately tell if the toaster is full of crumbs or not usually, so I try to empty is often! :)

As for a range hood, if it's vented to the outside, it will make a difference. However, I will admit, in my current house, our range hood, though vented outside, doesn’t get all cooking odors, but it does vent at least some of them. My house is a 1950’s stone/concrete block house, that is relatively leaky, so I’m not generally worried about indoor air quality in cold weather, but I have noticed that it can get a bit stuffy in humid 70’s when the A/C doesn’t run so much, which is when I open a window for a bit.

As for having all houses go all electric for all heating/cool needs, I’m not convinced that it’s an ideal solution for all areas of the country. I think south of the Mason Dixon line, you can reasonably go all electric, without any big issues generally, even with normal homes that aren't super well insulated or very tight.

I live in Pittsburgh, PA. And our winters can get cold, average temps in Dec through Feb are in the mid 20’s, but it will hit low teens at night, and we’ve hit zero on occasion. I have an efficient gas furnace, with plenty of heating capacity for my 1950’s relatively leaky concrete block/stone house (we’re making progress on that, but it will never be like a new tight house)

I have sufficient heating capacity, but insufficient ductwork in a couple areas of the house. So, I am in the process of installing a MR Cool mini-split - DIY-MULTI3-27HP230C (3 zones), to supplement the mediocre cooling/heating in our large finished attic area (65F/80F winter/summer), and my wife’s finished porch office area (similar temp ranges). Running new ductwork is a very expensive endeavor, and not worth it in our case.

This unit is rated at 27K BTU heating @ 47F. It’s rated @ 20K BTU @ 17F, and 19K BTU @ 5F. So, in theory, it should be very helpful for supplemental heating for the majority of the winter, and for cooling the 80F attic in the summer time. And with gas prices going up, I may experiment with turning down the gas furnace thermostat to 65, and allow the heat pump to run more, especially when it’s in the mid 20's and higher. I only ordered two indoor air handlers, but as it can handle 3, I may just order and install a 3rd indoor air handler for my living room.

Depending on how my experience is with the MR Cool mini-split for heating and cooling, I am considering using the same type multizone mini-split for our soon to be built 1500 sq foot addition. I’m planning on ICF (insulated concrete forms), for the entire two story addition with finished attic. The addition will be super insulated and tight, so I suspect the mini-split will work perfectly for it. Though, I may also put in a fireplace insert for supplemental heating in emergency situations and for ambience. And of course, it will need an ERV for indoor air quality.

Non-rhetorical questions:

What is the leakage rate overall for the natural gas distribution system serving residential areas?

My perhaps incorrect notion was that it was similar and percentage to the unburned methane rate of natural gas ovens and cooktops. But I don't have the data right now or studies support that. However, anecdata from my own house (itself dangerous notion in policy discussions) supports that the leakage rate is quite significant in the climate discussion. I recently discovered that my furnace was leaking gas due to a leaking valve- and my house is a very common type in my neighborhood with all similar systems and similar vintages. Also, my storage unit burned down several years ago due to a natural gas leak that was presumably going on for a long time, unnoticed, until it finally found an ignition source.

And then there's the Natural Gas Distribution Hub that I used to ride my bike by every day on my commute that always reeked of mercaptan. This all adds up to something more, but I dont know how much. Most people dont really care how their energy services are delivered (iso long as the beer is cold and the shower is hot), but cooking is an exception, and therefore a focal point here.

As homes electrify ( which was already a strong trend in my world as of a decade ago due to the superiority of heat pumps serving homes in the California energy market), how much longer is the utility world going to be able to rate-base the natural gas system to serve each home a therm or two a month for cooking. We might as well go LPG. Indeed that's what my household has done for the few times we want to cook with our trusty old wok.

My brother has always done wok cooking outside on a propane burner. There are also dedicated induction woks, which I am told work pretty well.

One thing that colors my view of gas is an explosion that happened a few miles from my house about seven years ago. Several businesses were leveled and nine of the firefighters ended up in the hospital. I don't think anyone was killed, but it was just luck it was closed businesses at night and not an apartment house or something.

The EPA estimates that about 1.4% of all the natural gas produced in the US is leaked. Definitely adds up.

A house in a neighborhood where I work was completely obliterated a few years ago, due to a propane explosion, and a contractor I work with's mother was severely injured when a commercial building exploded due to a propane leak, killing and maiming others as well. It's rare but it happens enough that safety should be a factor in decision-making when it comes to gas and propane.

This can vary a lot by state. MA has gas lines sealed with jute dating back to the Civil War. The leaks from that are estimated to wipe out all the carbon saving measures the state engages in. A local organization HEET tracks some of it. See https://heet.org/2022/11/23/fixing-super-emitting-gas-leaks-shared-action-plan-update/

Am I wrong to think that air-source heat pumps need a supplemental heat source when the temperature falls below 30F or there abouts? What about that?

Recently we moved. My wife, married to her dual fuel stove for 20+ years, is now barely on speaking terms with the electric non-induction cooktop in her new modern kitchen (either too hot or too cold, so easy to burn eggs). I hope to induce her to go with the magnetic version, but she is suspicious; and she anticipating the loss of her favorite old pots & pans that aren't magnetic. It's not just AGA marketing that made believers of gas cooktops: it's just easier to use. Maybe that NY Times article is a good one - who knows because it's behind a paywall. So does an induction cooktop actually improve cooking? e.g: is it easier to make Creme Caramel (or some such item) or is it just a ploy to spend more money? Sorry for being so cranky.

"Am I wrong to think that air-source heat pumps need a supplemental heat source when the temperature falls below 30F or there abouts? What about that?"

Yes you are wrong. There are several manufacturers making cold climate pumps that operate to negative F digits (Mitsubishi, for example, has hyper heat units with ratings down to -13F).

Induction vs resistance is no contest. Induction is much more responsive and faster to heat.

I watched as from the 90s on kitchens in houses became more elaborate and incorporated commercial fixture and appliances - while at the same time less and less cooking took place in homes.

I have several friends who are chefs and teach cooking at local colleges. I have shared lots of meals with them that they somehow managed to cook on old resistance stoves.

Sure induction is better, and I would prefer cutting plywood with a Festool track-saw over a Makita, or swinging a Stiletto over a Dewalt framing hammer, but there is a part of this whole debate that strikes me a bit precious.

I agree. But Dan wanted to know if induction improved cooking (I took that as vs resistance) and I think thr answer is yes.

I use a makita track saw. And my current stove is resistance :). But I've had an induction stove (no festool track saw unfortunately) and its definitely an upgrade.

I think the sell on induction is to get people using gas willing to replace. They will never want resistence-- induction is a closer match.

Maine_tyler,

I certainly didn't mean to direct any criticism at you, it's just frustrating sometimes that the debate over making changes for climate or energy savings needs to overcome this high bar that it also has to be an improvement in performance. The whole "I won't give up my Ford 350 I only use to meet my other retired friends for coffee, until the electric equivalent surpasses all the features it has" attitude.

Malcolm,

I didn't really take it as criticism, though I can see why my response would make it seem as such.

I think your point is a really good one. Unfortunately a lot of people do need to be 'sold' on being green like you say. I go back and forth on whether 'selling' green is useful or counter-productive. Though arguably, 90% or so of the content on GBA is selling a form of high-end greenism (namely high performance homes).

I don't know. I like GBA a lot, and find it very useful, but like you I'm not sure in the bigger scheme of things it makes much difference. Maybe that's not the metric we should be using to judge everything though? Honestly, it's a bit beyond me, and that's why I usually restrict my comments to the practical problems that get posed here.

For sure there are bigger levers to pull than the ones we can pull here on GBA. But I agree, that doesn't mean it's not a worthwhile endeavor. Helping to spread information that will—in theory— help people to renovate or build in ways that are healthy, robust, efficient, and low carbon sure seems like a good thing.

Anyone thinking they know precisely which levers to pull and which are meaningless most likely has some practice in the art of self-deception. There are no easy answers and we're all feeling our way in the dark using the leverage points we have available.

We’re in our seventies, and tend to forgetfulness at times. Like yesterday when I got distracted after talking the pot of oatmeal off the gas burner. She noticed it a while later and turned it off. Induction stoves will shut off if there is nothing on the burner, or if they overheat. Or if you get distracted and walk away. Just saying there are practical reasons for buying induction. I’ve installed several in the houses I’ve built; owners all had and loved gas; they like the induction better.

Much ado about nothing. Vent your cooktop. Nothing wrong with natural gas as long as it is plumbed correctly. Nothing wrong with induction as long as it wired correctly. Vent your cooktop and provide makeup air. Stop worrying about carbon and start planting. Use only what you need. Pretty damn simple.

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in