Image Credit: All photos: Michael Henry

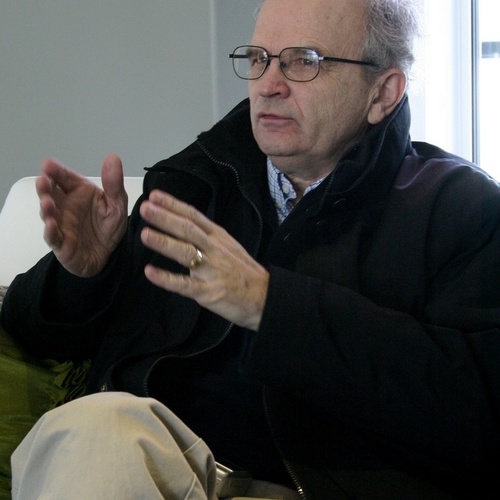

Image Credit: All photos: Michael Henry Robert Dumont is so proud of his drainwater heat exchanger that he left it exposed for visitors to admire. Rob Dumont installed his windows as "outies," so the house has deep window stools. Note that the window rough openings have splayed jambs. Robert Dumont, superinsulation pioneer.

The first time I saw Rob Dumont’s house, I was unimpressed. I was visiting an ex-girlfriend in Saskatoon, I mentioned that I was doing some research into sustainable homes, and she said, “There’s one near here. We should walk by it.”

It looked just like any other house. The Dumont house is in the colonial style. It’s simply built and doesn’t stand out in the neighborhood, which has a suburban feel to it (though it’s not far from the downtown). I’m used to seeing half-million dollar ecohomes. When you take away the architect and expensive finishes, solariums, thermal mass walls, radiant floors, etc., the Dumont house is hardly recognizable as an ecohouse.

I arranged to go back later and visit Rob Dumont, who gave me a tour of his home and some other projects he was working on. What initially turned me off about the Dumont House (because it challenged my preconceptions) now makes it one of my favorite sustainable homes.

The walls are 16 inches thick

When Dumont built this house in 1992, it was recognized as one of the world’s most highly insulated homes – but the house, like Dumont himself, is understated. Dumont took the double-wall system from the Saskatchewan Conservation House, stretched it out to a full 16-inch-thick wall cavity, and filled this space with blown-in cellulose insulation (which is just recycled newspaper with borax added for fire proofing and pest control).

There are about 16,000 pounds of cellulose in the house – but what makes this insulation system really special is that the two walls have very little framing between them, so there are far fewer pathways to lose heat through the wall, either through leakage where the insulation doesn’t meet the wood perfectly, or by thermal bridging through the wood itself.

It may seem obvious, but it needs to be said: wood is way worse insulation than insulation is. A 2×6 stud wall with R-20 insulation batts has an overall insulation value of about R-13. Rob Dumont’s walls are R-60, the attic is R-80, and the windows are R-5. The whole house is carefully air sealed. It takes less than 1/4 of the energy to heat Dumont’s house that it would for a conventional house. (In 2000, Dumont wrote an article describing the energy efficiency features of his home.)

Drainwater heat exchanger

As we continued the house tour, Rob showed me some things that really could be added to any existing house. The first was a drainwater heat exchanger, which is just a copper tube wrapped around the shower drain. As hot shower water comes down the drain pipe, the cold incoming water in the coil is warmed. “On a shower it will recover about half of the heat that’s otherwise going down the drain,” said Dumont.

He quipped, “I’m worried that with the price of copper, in a home invasion someone will steal it.” Still, barring home invasions, the economic payback is pretty quick: if your hot water heater is electric, the heat exchanger will pay itself off in 5 or 6 years; with gas heater, maybe double that.

Next we looked at the hot water heater itself, which is a standard tank but wrapped with batt insulation and a thermal blanket adding up to about R-28. “Without the insulation, it loses about 100 watts of heat continuously,” Dumont said. “With the insulation, it’s down to about 25 watts.”

Because of the simplicity of the Dumont house, it wasn’t expensive to build. The insulation, upgraded windows, and solar thermal system added about 7% to the building cost. “If I’d put brick on the outside of the house instead of hardboard siding,” said Dumont, “the brick would have cost more than all of the energy conservation features. I’d much rather have an energy efficient house than a brick house.”

In fact, the energy-efficiency measures (which cost $13,000) finished paying for themselves in 2008, after 16 years. Now the measures are turning a profit. And he pointed out other non-monetary benefits: no draftiness, no cold feet, and the nice aesthetic of the deep window ledges.

“Always have your sails up”

Rob Dumont, like many of the builders and designers I’ve met, started his work in the 1970s, and spent some time wandering (metaphorically) alone in the desert in the ’80s and ’90s.

“Society has got a very short attention span,” he said. “There are waves of interest, but mother nature bats last. I started working in the ’70s on the Saskatchewan Conservation House. One had to really keep the faith through a part of the time since, because not many people were very interested. I must admit that back in 1973, with the oil shock, I thought the reasonable thing to do would be to change the way we do our houses radically. That was my youthful naïveté at the time.”

He showed me a book of solar homes that was written in the late 1970s, a sort of hippie version of what I’m trying to do, and I realized that I’m just the latest emissary of societal interest, something Dumont has seen come and go. I feel like this time it may be different, but I’m not sure. “It’s encouraging,” said Dumont, but “it’s not nearly at the level I’d like it to be. E.F. Schumacher put it nicely: he said the wind may not always blow, but at least we should have our sails up. That’s the way I feel.”

Rob and his wife Phil took me to see a college basketball game, in which the home team, the Huskies, thoroughly trounced the competition (both women’s and men’s teams). I pictured Rob in his younger days playing basketball, fit and idealistic, believing he could change the world. And he did – it just changes very slowly.

I wonder, when I look back in another twenty or thirty years, how I will remember this time. As the beginning of real change, or as lost opportunity? All I know is that my visit with Rob Dumont left me more optimistic than when I arrived.

Michael Henry is a straw bale house builder who is curious about all aspects of green building, and blogs about it at The Sustainable Home. He’s also the author of Ontario’s Old-Growth Forests.

Weekly Newsletter

Get building science and energy efficiency advice, plus special offers, in your inbox.

One Comment

Rob Dumont

I'm happy to see Rob mentioned in your post. He stepped up and built his house when the rest of us were doing paper studies or monitoring other folks' houses. As this work predated the access we now have to research on the web, it is relatively obscure now.

You may be interested in a paper I coauthored as an employee of Brookhaven Lab in 1983 on the subject. I recently dug up a copy in my posession and put it up at;

http://issuu.com/flash.swank/docs/case_study__blouin_superinsulated_house

Thanks again for your post.

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in