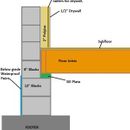

Concrete Block and Polyiso Foam Wall Assembly

We are in zone 4a, near Nashville.

Can you evaluate the wisdom or folly of my buddy’s wall assembly?

Whit is planning an unconventional wall assembly and I am worried he might be driving off a cliff. (Pic shows wall assembly).

I spoke to him about it and he has confidence it is fine, but I question it, and he was grateful for my offer to ask some pros on this forum to give some feedback.

As can be seen, he thinks 2″ of polyiso is all the wall insulation he will need.

His block cores will be hollow except for every fourth void.

Roof will be conventional vented attic).

He wants a durable house for things like tornados, etc…

I tried to convince him to use ICF foam blocks, but he is worried about blowouts during the pour.

I hate to watch someone make a huge mistake, but I am not knowledgeable enough to evaluate this. I have read enough to know I am not interested in pioneering with my little knowledge.

Thank you.

-Mike

GBA Detail Library

A collection of one thousand construction details organized by climate and house part

Replies

This is a good source for this type of assembly:

https://www.buildingscience.com/documents/digests/bsd-114-interior-insulation-retrofits-of-load-bearing-masonry-walls-in-cold-climates

What he is proposing is not without risk, I've tried similar wall in Zone 5 and it turned into a moldy mess, had to tear it all out and redo it with spray foam. The problem is any moisture that gets between the foam and the masonry is essentially stuck.

I would insulate from the outside or with spray foam from the inside. EIFS is a great option so is standard siding installed over exterior rigid.

Since polyiso is open cell, won't any moisture between foam and block wall dry inward through the foam and through the drywall?

2" of Polyiso seems woefully insufficient? Does this assembly enhance it?

What about poyiso between blocks and header joists?

Note, that is not a treated band joist.

I'm not sure what your building code says but the 2018 IRC for CZ4a says that mass walls need at least R-10.2 continuous insulation (according to the U-factor option) or R-13 (according to the prescriptive option). Polyiso is about R-5.6/in but sometimes sold as R-6.5/in so he's right on the cusp either way. That's to achieve "the worst house you can legally build;" it will almost certainly make financial sense to go about 50% higher with R-value, but to add even more embodied carbon to this assembly would be unfortunate.

Polyiso isn't open cell; it can absorb a small amount of water but chemically speaking it's very similar to closed cell spray foam. It will allow a small amount of inward drying but not a lot, and only if the facers are vapor-open.

Mike,

Fiber faced polyiso is somewhat permeable, at 2" it is about 0.5perm so not great. The wall I had fail used faced rigid, so maybe something with better permeability might work.

If this was my place, I would not take a chance and insulate it from the outside with rigid from the inside with SPF. If neither of these options are cost effective, the next best would be fig 11 from the link. The only thing sucks more than paying for spray foam is demoing a finished wall, cleaning up the mold, paying for the spray foam and rebuilding it.

Untreated wood in masonry is never the best idea but if they are well above grade, it is generally not an issue. I would insulate with a thin layer of unfaced XPS to allow for some drying.

Also,

With the great advice I see you dishing out all the time, I’d love to hear all about this failure, and what you saw as early signs, and how long the rebuild took, and all that. That would make a great article imo!

Kyle,

Not much to say here. The place was under construction during the period so there was some bulk water exposure to the wall. Not anything major, water running down the exterior surface but apparently enough. The wall work great during the winter, once the weather and the wall warmed up, it started smelling of mold.

I cut an access hole to confirm and there was a lot of moisture between the rigid and the masonry. I tryed putting a fan there with the intake taped tight against the rigid and ducting it outside to dry it out. This ran for about a month straight and did reduce some of the smell but wasn't gone.

Finally had to bite the bullet and demo the wall which confirmed that it was indeed a big mess back there. The surprising thing is the fan didn't do much drying, even a couple of feet away from the hole, it was still quite wet.

Sample of 1 , so take it with a grain of salt. My conclusion from this is that wall can work but not robust. If moisture does make it in, it is too slow to dry out. Maybe with much more permeable rigid it could have worked but I think it is still a risky assembly.

Akos,

I've been following this discussion partly because I know next to nothing about CMU construction. Do you think there are similarities between what happens in these above grade walls and what happens in basements insulated in the same way?

Since they are bellow grade basements are different and forgiving in some ways.

The foundation should be water proofed so no bulk water should get in there. They are also much warmer even in the winter time so much less chance of condensation. There is also no solar vapor drive which I think did the bulk of the damage in my case.

Akos,

Thanks. Although they are structural, I guess a CMU (or exposed concrete) above grade wall, is essentially a reservoir cladding, with all the attendant problems that can come with that.

I think this wall assembly in Nashville is almost great, if he were to put the insulation and furring strips on the outside. On the inside it’s a recipe for eventual freeze thaw spalling. Nashville gets cold and warm several times rapidly every winter. I’d rather have the entire structure be warm. I think 2” of polyiso is sufficient really. 3” would be better, but Its more than R13 batts into a typical 2x4 wall spaced 16” OC, by the time you add the siding, air gaps, and drywall on the inside.

How would that make it "almost great?" It barely meets code minimum, using climate-damaging materials. I'm honestly curious how you think it's an assembly that warrants better than "OK" on a green building website. I suppose it's potentially durable, but that's not saying a lot.

Because I know that outside of our community, large changes are hard and the only way we're going to change is incrementally. If code minimums require a certain R value for a wall assembly, that's what the bank is going to give loans for, and it's what appraisers, for better or worse, think all houses have at resale time. That's what most people are going to have to budget against, and what most people are going to be able to buy. It's a crime of the universe, but such is life.

The 2021 IRC requirement for mass walls in zone 4, where all insulation is on the exterior is R8. This is better than that, if you count the polyiso as 5.5/inch, by 38%. While I would improve it myself, others may choose to spend that money elsewhere. I don't know his exact address, but it's entirely possible that his locality isn't even on an IRC from the last decade.

It's not a bad assembly, it's basically Joe's "500 year" perfect wall. It checks many of the boxes that make for a long lasting healthy structure. (1) keeps everything warm and dry (2) follows the PERSIST paradigm (3) can be constructed with available materials and local trades (4) extremely long lasting, with the caveat that other parts are done equally well.

More insulation would be great, but lets not kid ourselves into thinking that every wall needs to be R25+, especially in the south. The climate gets a lot of rain, has muggy hot summers, and kind of cold winters. (I think it's cold, but average lows in the 20's isn't really all that cold I guess...)

Edit: I'm not sure we should bash the IRC codes as much as they use to warrant in the past, "the worst house you can legally build". Is an R60 attic the "worst attic that you can legally build"? Of course not, it's overkill and quite good.

Kyle, those are good points. I wasn't thinking about the code difference of insulation location in a mass wall; on the interior it's R-13 but on the exterior you're correct that it's R-8 in CZ4. When forced to use insulation materials with high levels of embodied carbon I believe in most cases it's best to stick close to the code. I would rather see homes built with sustainable materials but agree that your version of this design works well from a building science point of view.

Sometimes I wonder, more often lately, that this site should have been called "building science advisor" and not "green building advisor," since very little of the Q+A is about building with green principles in mind, and when articles about green building principles are posted there are usually responses arguing with whatever "green" principles or materials were discussed. But it's a good place for BS discussions.

I was pondering on your second paragraph, and I think that there's still some space between what's considered best practice (Building Science) and its implementation (Products and techniques). I also think we're all trying to accomplish the same thing, which is produce buildings that minimize their impact on the planet, while being beautiful, long lasting, inexpensive, and healthy. I also think everyone has some amount of bias that depends on their background, where you're standing, and which direction you're looking in terms of what's considered green building. If you'll excuse my artistic ability below,

Sustainable green products --> Goal <-- Performance building

^

| X

Long term durability

Ideally these three subjects wouldn't be independent of each other. I'll admit to having a bias more towards the BS and long term durability (myself standing on the X), and I suppose it has some inherent drawbacks on a lot of my suggestions, in that to be 'green' it requires that the building stand in place with somewhat little modification for long enough to average out lower than multiple buildings replacing it. I want that position to shift up to the left towards the goal. The problem (dilema?) that I've often faced is that to implement what's best, BS wise, it requires the use of materials that for the lack of a better phrase, aren't green. To make it worse, they're often higher performing, and cheaper.

As more products come out that are both green and high (enough) performance, I'd love to be able to recommend wood fiber as opposed to comfortboard, but right now it's just not feasible. I'm still only 30/70 on THQ ever shipping at volume, despite all the press. Dense packed cellulose is cool too, but can a guy just get a semi-rigid batt? The same goes for an alternative to polyiso, I think wood fiber could work here too, but at half the R/inch and twice the weight, and higher cost, it's going to be a rough road, especially on commercial roofs. You can tell people that non squishy EPS exists, but when they call, or have their builder call (already one strike), they're often met with "Yeah, we can get that, but it's special order with a lead time of K weeks". Animal wool, hemp, straw, and insulation++ are cool, but they're also pipe dreams for any real impact when you consider the product of volume shipped X price.

Another aspect of this, is that materials like concrete aren't really bad, they're a technological marvel. They've allowed societies to come together in densities that allow us to advance culture, science, art, and generally everything we strive to improve for. The current methods impart a large amount of greenhouse gasses, and that is bad. But what if cement were generate purely by renewable energy, and the CO2 driven off in the process was captured? It would be the pinnacle of materials. The same goes for other high-embodied materials like Rockwool. What if that process were net zero? We'd have an insulation that checks practically all our boxes. That's more or less why I don't disregard those materials. The methods to produce them now aren't all that great, but in the future they might be fine, and I'd hate to lose all that knowledge surrounding it.

In summary, I think we're all on the same team, trying to get to the same place, we're all just standing on different parts of the field, trying to score the same goal.

Response to #17: that's an interesting way of looking at it. I have a similar approach; after struggling with how to balance the important impacts, I came up with, in order of importance:

1. Occupant health and safety.

2. Building durability.

3. Environmental impact.

There are other aspects to building green, sustainably, high-performance or whatever terms you want to use, but those are the big ones.

I agree that concrete is a miracle material, and so is foam--both can do amazing things, and you're right--if they did not have their negative environmental impacts (and preferably lower risks to those who work with them regularly--my grandfather was a concrete foreman and died young of silicosis) and if the raw materials were in unlimited supply, they would rightfully dominate the market, even more than they already do.

But that's not the case; both materials are still amazing at certain tasks, but they are used indiscriminately, often resulting in increased risks to #1 and #2 on the list, while completely disregarding #3. For example, the OP's assembly is at high risk of mold, and with the insulation on the interior it's at risk of exterior spalling in cold weather, which is showing up more often in warm climates than it used to, so the assembly does not meet any of the three items I listed. Your version of the assembly solves #1 and #2, but is nearly as bad as it gets for #3.

As more l0w-impact materials become available and professionals get more used to working with them, it will be easier to hit all three items on my list. Meanwhile, greenhouse gasses continue to accumulate and our climate continues to become less stable.

Posts #17 and 18, Kyle and Michael, both excellent summaries. Thank you both.

One product I don't see covered here much is cellulose batts. They appear to install much like mineral wool; maybe they're more green? I only know about one manufacturer, EcoCell, so distribution/availability could be limited. The batts also contain 10-20% PET as a binder. Curious if anyone has worked with them.

Bruce King and Chris Magwood's book, Build Beyond Zero has a lot of interesting stuff about low-emissions advances in cementitious materials, although most are still in the early lab phase.

The building is being built near Nashville.

What about the blocks being hollow except every 4 feet or so? Does that have any impact on the design?

I noticed the word "mass" in a reply, and it made me think these blocks are going to largely empty.

This is the definition of a mass wall: https://codes.iccsafe.org/content/IRC2021P1/chapter-11-re-energy-efficiency#IRC2021P1_Pt04_Ch11_SecN1102.2.5. Having unfilled cores reduces the "thermal mass," the combination of specific heat capacity and mass that slows heat movement. It only has an effect when temperatures are changing, and even then the effect is small and can usually be ignored. It can also be a way to capture solar energy, but the amount of heat that can be stored that way is pretty low.

Don @ post #19

When I asked if a guy could get a semi rigid cellulose batt, I was throwing a reference there to the ecocell. I wish there were more manufacturers for something like it. They are the only ones as far as I’ve found, but their shipping costs make it infeasible if you’re not close to one of their retailers. I once tried to get a truck load shipped to Alabama, but I couldn’t even justify it to myself, let alone others. Property wise, It’s too close to fiberglass to go very far out of the way for it.

I try to keep a finger on the pulse of advances in concrete. It’s an something of an odd obsession. I’d say that if it were more common, we could get away with lime/pozzolans or slag cement in the place of Portland cement, but again it’s another one of those niche types of building things that’ll never really be used at large.