Author’s note: This series is aimed at the home performance industry. My company values transparency, so we put it in the public sphere for homeowners to see and understand our thinking.

In a recent article, I told the warts-and-all story of how energy efficiency program design was a huge factor in putting my award winning business under. I promised to talk about solutions this time.

If you are the type whose initial response to new ideas is typically; “No, No, NO!”, you probably should read no further.

… If, on the other hand, you are comfortable having your schemas stretched and altered, if you are open to and enjoy having your thinking challenged, hopefully you will enjoy this.

You’ll note that my tone in this article may be a little harsher than usual. There was no other way to write it. At some point, no matter how nicely you put it, those who stretch the truth may find the truth offensive. Ultimately this is not an attack on bad people, but rather bad structures. This series of articles is an attempt to expose harmful program structures that pervert process and prevent optimized outcomes — and then to offer a different path, a path that removes perversities and aligns all stakeholder interests.

The phrase “energy efficiency programs” (or just “programs”) refers to utility-sponsored or state-sponsored programs that offer homeowners a rebate, incentive, or subsidized financing to make energy efficiency upgrades in their homes. Many of these programs work under the Department of Energy’s “Home Performance with Energy Star” program (HPwES).

Goals of “One Knob”

Whining without proposing a solution is an awful thing to do, so here are three key goals that any good program should achieve. These three things are necessary components to keep programs on track. Without these attributes it is unlikely that Home Performance (HP) will ever scale:

- Focus on results. Let market forces rule. Free contractors to sell projects that solve homeowner problems. Get bureaucrats out of project decisions and leave the improvement decisions to the collaboration between homeowners and contractors. Stop telling how to achieve program goals — just provide rewards to the extent that program goals are achieved.

- Accountability. Provide real accountability and real energy savings. No more claiming credit for “hopeful projections.”

- Market transformation. Deliver remarkable results to homeowners so that they tell everyone they know.

These sound nearly impossible, don’t they?

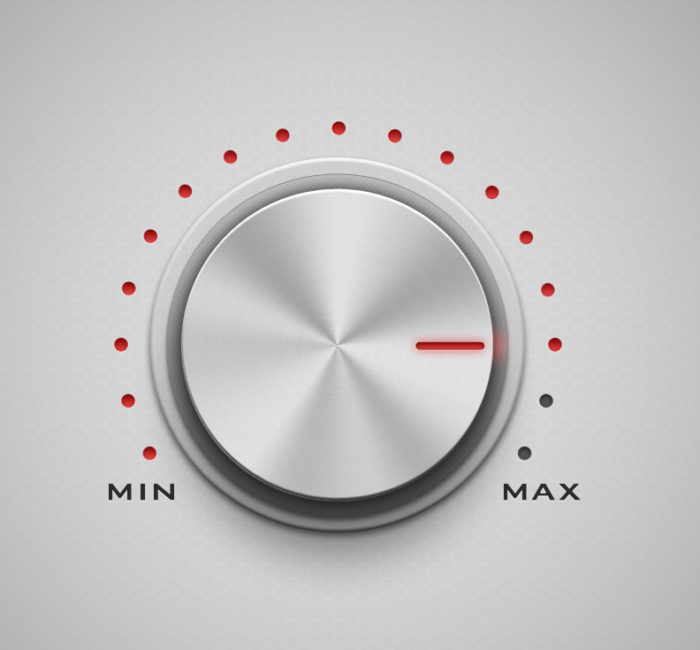

They’re not. They can all be achieved with a program called One Knob (as in “one volume control”). Even better yet, this can be achieved with current contractors, current employees, current programs, current equipment, and current technology. It will take a little retraining, but not much.

(Briefly, the “One Knob” proposal calls for the level of incentives paid to be based on saved energy. If 10,000 kWh per year are projected to be saved, and the rebate is $.40 per kWh saved, then the homeowner gets a check for $4,000. Contractors have the most control over results, so the contractors will make the projections. The program will publish contractor metrics — that is, actual energy savings compared to projected savings — and will rank the contractors based on these metrics. High-ranked contractors will get automatic job approval, leading to less administrative overhead for the contractor and the program.)

I’ll eventually fill out the program concept. But first, a discussion of what currently exists, and then what is possible to attain for the three desired goals (a focus on results, accountability, and market transformation).

What exists today: Programs built without considering results

Energy efficiency programs are complicated. The simple ones like the one that killed my business have simple rules, but they complicate work scopes, the sales process, and the jobs themselves. More complicated programs have rules so complicated that they are laughable, except it’s not funny. (1)

In part, this comes from programs trying to make sure homeowners, ratepayers, and taxpayers don’t get cheated, but they end up cheating homeowners out of results and contractors out of sustaining profits.

Stakeholder priorities are badly misaligned, as well. Program objectives are for high project count and to claim the highest amount of dubious energy savings possible. Homeowners don’t care that much about saving energy; they’re more interested in solving comfort and control problems, and frankly they are very skeptical of energy savings claims.

Programs control from above

Currently, either directly or indirectly, project work scopes are created by bureaucrats who don’t actually do or sell the work. These bureaucrats don’t talk to the homeowner, they don’t have to manage the crews, they don’t have to worry about overhead or any of the other things that come with running a real company, and they don’t worry about homeowner outcomes.

This is true of both the simple rebate programs like the Dominion East Ohio program in my region, or the programs created by Efficiency Vermont, or the much more complex programs in New York and California. This makes working with programs very complex and screws up incentives, because all parties are pulling for different things.

Incentives are misaligned and often perverse. Check this out: “There was a huge emphasis on quantity even if the quality was very poor. Managers often resorted to lying to meet unrealistic quotas. They suffered from perverse incentives that placed fulfilling political goals ahead of efficiency. Firms in general had little incentive to be efficient or control costs.”

That sounds like home performance programs, doesn’t it? It’s actually from a blog by Robert Nielsen about why communism failed. The author goes on to say, “One of the greatest failings of communism was its inability to innovate.”

In the end, what was one of my biggest complaints about the program I worked with in Ohio? My flexibility was severely limited; I couldn’t innovate. I had to do work one way: the way the program wanted. I was not able to let market forces work and deliver what clients were looking for. We just chased rebates, taking our eyes off solving systemic problems. This seems to be true of every program in the country.

While it’s still early, my current projects which receive no program assistance are running in the $15,000 to $40,000 range. My old average job was $2,500. This is what happens when you slow down, build trust, and really focus on homeowner wants and needs. There are still trust barriers that impede sales. If these projects had third-party results tracking and could get incentive for energy savings, or on-bill financing, this approach is likely to take off.

Trouble at the kitchen table

Programs make life at the kitchen table, where all projects are sold, much harder. They are friction when we need grease.

Complex rules change; work scopes get changed to fit rebate or fuel type requirements; jobs get adjusted on the fly; rebate structures change; jobs get shut down because they don’t meet payback requirements… and on and on.

One of the worst problems caused by managing projects from above is that it creates a culture of collusion. Contractors are often forced to lie to get a job approved and pay their bills. (2) Program implementers spend time teaching contractors to game models to “pass” instead of helping them improve diagnostic and design skills.

Programs are essentially trying to control home performance work from the top down, not unlike the communist-controlled Soviet economy. How did that work out again? To be fair, this is true of most large bureaucracies. The term “red tape” exists because of bureaucracy.

Summing up: programs just aren’t simple or results-focused, and this leads to all sorts of accidental barriers that keep home performance work from scaling up.

Focusing on results: What could be

What if programs only had One Knob to adjust? What if this simple adjustment was aimed specifically at delivering actual energy savings and solving homeowner problems?

One singular adjustment that could be changed, with changes that could be announced months in advance, so there weren’t ugly surprises at the kitchen table? What if this knob could be used to speed up or slow down the market predictably like the Fed does with the discount rate? What if this could drive us towards performing comprehensive energy retrofits to millions of houses instead of thousands because it actually solves homeowner problems?

What if a massive industry focused on results could come into existence, one that could finally put a happy ending on the Great Recession? One Knob can do this. Details are coming. Stay tuned.

Accountability: What exists today

Currently there is no real accountability for results, either for solving homeowner problems or for actual energy savings.

Contractors can blame programs for hamstringing them when projects don’t deliver what was promised. Programs can blame contractors for doing shoddy work. Utilities take the “lies” from programs to give to Public Utility Commissions mandating energy savings, and nothing really gets accomplished. Fingers point every which way.

Homeowners spend lots of money with mediocre results, and contractors are exhausted by constant program changes created by bureaucrats who make these changes to justify their existence. No one party actually is accountable or rewarded for actual results.

To repeat, this is not the fault of people; it is the fault of the structure. Programs are not market-based.

Programs often have absolutely shocking costs per project due to a lack of accountability. Energy Upgrade California has spent $200 million in overhead costs since inception to deliver 3,615 jobs. That’s $25,000 per job in overhead, before incentives. (3) This is for jobs that are substantially smaller than $25,000 each. Worse, those projects deliver to the consumer only one third of the energy savings projected by Energy Upgrade California. This program has achieved less than 10% of its goal, by the way.

California is easy to shoot at because it has been so ridiculously wasteful. Their 34% realization rate is the worst of the published program results. New York is in the 45% to 75% range, depending on fuel.

Other states have published results which hover in the 40% to 60% range. Who is holding these folks accountable? If a friend borrowed $1,000 and paid you back $600 and said, “We’re square,” would that be good? That’s what programs and our industry are effectively doing. We’re lucky no one actually tracks their energy bills, or there could be a lawsuit. It doesn’t have to be this way.

All the while, naive and idealistic contractors struggle to make a living in the home performance field. I tapped out with a program-dependent business model. The system is wasteful, inefficient, and can’t provide a decent standard of living for contractors.

In the current world of contracting there is a fervent race to the bottom on price and quality. I starved to death trying to provide quality without charging enough for it, and Energy Smart is far from alone. Chris Dorsi, author of Residential Energy and founder of the Habitat X Conference, advocates for higher pay scales for insulation contractors, so it’s a common problem.

Without metrics for quality or accountability for results, doing anything more than the bare minimum is a competitive disadvantage.

Accountability: What could be

Accountability, through the trust it creates, can be its own reward. One Knob can create a system where excellence is recognized and exalted. This will push the best contractors to the top and allow them to charge more for their services.

J.D. Power and Associates did this for the automobile industry. The company took an industry with terrible quality and no metrics and created a ranking. The ranking rewarded Honda and Toyota and almost bankrupted the Big Three. Now quality is significantly better throughout the industry, and ten-year-old cars with 150,000+ miles are common. Consumers and the high-quality companies won; low-quality companies had to raise the bar or die.

Once you make quality a ranking metric, quality matters. What is quality in home performance? Measurable results.

The home performance industry is one of the few construction disciplines that actually has measurable results, not just customer satisfaction metrics. We have lots of metrics to rank contractors on: actual energy saved, actual vs. predicted energy saved, actual blower door reduction, actual vs. predicted blower door reduction, $ invested/energy saved — the list goes on and on.

With HPXML, we have access to ALL of this. (HPXML is a central database that pulls information from various energy modeling software for easy analysis by programs.) We have this right now. Today. Very little new is required.

Market transformation: What exists today

I was born in 1978. Energy efficiency programs have been in place in one form or another since then. I’ve heard that at current job volumes, it will take 500 years to retrofit the homes that need to be retrofitted in the next 20 years.

The large Home Performance with Energy Star (HPwES) programs were projecting 0.5% growth for 2013. Wouldn’t we need just a little bit faster growth than that to get there? Tell me how we’re achieving market transformation right now?

I’m a home performance consultant. I was an home performance contractor. Yet I couldn’t define home performance for you three years ago. We only barely have a name for ourselves. Consumers have no clue who we are. About one home performace job per 1,000 HVAC jobs is done, according to the recently passed Phil Jeffers. How is that “winning”?

California has only hit 10% of its goal. New York is watching contractor participation, job size, and job count fall. My program with Dominion East Ohio has turned into a glorified HVAC rebate program. One program in Connecticut is an HVAC-only program — how is that home performance? How is that comprehensive, whole-house thinking? How are we winning again?

Currently, the parallels between communism and current energy efficiency programs are so strong that I can literally lift passages of articles about what made communism fail and drop them into this paper.

Could anything that can be so directly and easily compared to communism possibly be expected to achieve capitalistic market transformation?

Market transformation: What could be

What makes someone excitedly tell their friends about something? A spectacular result.

Comprehensive home performance work that goes beyond an attic insulation job, but stops short of a deep energy retrofit, can deliver spectacular results. If we gain sufficient control over heat, air, and moisture movement, we can deliver the Four Tenets of Home Performance: comfort, health & safety, durability, and efficiency. These are projects that anyone with about $75 a month or more to improve their home can do.

How nice is it to be comfortable in your home all the time? Or to not worry about icicles ripping down your ceiling ever again? Or to have your kid’s asthma, that landed him frequently in the hospital, subside? The home performance industry can deliver remarkable results. It truly requires systems thinking, but we can do it. And those results can help create a groundswell. Programs can play an important role.

Here are some of the benefits of home performance market transformation:

- A healthier, longer-lived populace, with reduced allergies, asthma, flu, colds, carbon monoxide poisoning, etc. (Health & safety is the second tenet of home performance, after all.)

- A more comfortable populace. Home performance work improves indoor environmental quality, or total comfort.

- A more productive populace. Comfortable people are more productive.

- A healthier planet: substantially reduced usage of fossil fuels (and an easy transition to pure renewables at little or no additional cost).

- Jobs. This is literally a trillion dollar industry at a very conservative $10,000 per home times 100 million existing homes. Think that could help out a bit in providing jobs?

- Happier, more productive, more innovative contractors. If programs were ridiculously simple yet provided solid accountability, contractors would be free to figure out results driven best practices.

The cliffhanger

That sounds pretty nice, doesn’t it? It’s within our grasp. We just have to get programs out of the way by focusing on results, implementing accountability, and using both of those to drive towards market transformation. This new program design, One Knob, is very simple and easy to understand.

More details on my One Knob proposal are coming in an upcoming article.

Want to help?

- Share the heck out of this! Comment! Make noise! Nothing is going to change unless we push for it.

- Go join the Linked In “Get Energy Smart” group. We’re going to need help making enough noise to get things changed, so please add your voice! We’ll update you with action steps there as well.

- Connect with me on Linked In and mention “One Knob.” Feel free to email me at nate [at] energysmartohio [dot] com.

Footnotes.

1. Here is an example of bad program design, but first a definition. A negawatt is a saved watt of energy, or negative watt, defined by Amory Lovins of the Rocky Mountain Institute. Here is an actual example of how the Negawatt kicker (incentive) works in the Energy Upgrade California program. Would you like something that works like this? Or something simple? The kicker is $0.75/kWh if the home doesn’t have existing AC, $0.30/kWh otherwise, and $1.60/therm. A minimum 10% total site savings needs to be projected. The percentage-based component starts at $1,000 and increases by $500 for every addition 5% projected. The electric and gas savings are then modified by factors designed to counter (as you might have guessed) historical over-projection. Kwh savings are left alone if no AC, but hit with a 0.4 modification otherwise (60% reduction). Gas savings are hit with a 0.8 factor. For instance, a home without AC that models 25000/18000 kwh existing/improved, and 1100/800 therms existing/improved would be 27.6% site savings. Modified by the therm factor, it would be 24.5% savings, which puts it in the $2,000 tier with a $5,250 kwh and $480 therm kicker, for $7,730. Is this the best we can do?!

2. In New York, jobs must “pay for themselves” and have a 1 SIR or better, meaning the energy savings from the project will pay for the project within the lifespan of the improvements. The trouble is, with current low energy prices, that just doesn’t happen. So what do you do? You lie. You inflate initial blower door numbers. You fudge the model to show really high initial usage. I have this directly, and off the record, from multiple contractors in New York. This also leads to crappy realization rates. If I promised to make your pickup truck get 50 mpg, is there any prayer I might deliver? Nope. But I had to say that to get the program to say yes to the project and feed my family. That is a great example of a perverse incentive.

3. This is per Ori Skloot in an update video about EUC 2.0. (Go to 2:30 in the video).

Nate Adams is a recovering insulation contractor turned Home Performance consultant. His company, Energy Smart Home Performance, is located in Mantua, Ohio. Using a comprehensive design approach, he fixes client woes with a market-driven process that he hopes will lead to market transformation for our industry.

Weekly Newsletter

Get building science and energy efficiency advice, plus special offers, in your inbox.

22 Comments

Leaving People Hanging...

GBA - Might want to hyperlink "More details on my One Knob proposal are coming in the upcoming article" to the next post so people like RJP who get all the way through and want to continue aren't left flat.

Response to RJP and Ted Kidd

RJP and Ted,

Nate Adams is apparently providing a strong foundation for his argument, to make sure that the details that will be revealed in upcoming blogs are well supported. Be patient; more details are forthcoming.

In the meantime, one paragraph from this blog gives an outline of his proposal:

"Briefly, the “One Knob” proposal calls for the level of incentives paid to be based on saved energy. If 10,000 kWh per year are projected to be saved, and the rebate is $.40 per kWh saved, then the homeowner gets a check for $4,000. Contractors have the most control over results, so the contractors will make the projections. The program will publish contractor metrics — that is, actual energy savings compared to projected savings — and will rank the contractors based on these metrics. High-ranked contractors will get automatic job approval, leading to less administrative overhead for the contractor and the program."

"This series of articles is

"This series of articles is an attempt to expose harmful program structures that pervert process"

"To repeat, this is not the fault of people; it is the fault of the structure. Programs are not market-based."

Its laughable that the author sets out to tell how to "unpervert" an incentive process and make it "market" based when the reality is that ANY incentive program by it very definition is a perversion of the market process.

The very reason an incentive program is put in place is to get people to change their current market driven behavior into doing something they otherwise wouldn't do without the subsidy. An industry (utilities) paying someone to reduce the use of the product they sell, is close to the ultimate perversion of the market and is done because of other perversions in the utility market (regulator interference to push questionable if not bogus goals).

The author proposes to fix the perversion of the incentive program without addressing the perversion (regulatory interference) the begets the perversion (incentive programs) that begets the perversion of the energy efficiency improvements market.

Heres a novel idea. How about we remove the regulatory edicts that demand that utilities pay their customers to not use their products and rather sell energy efficiency upgrades based on the ROI of the project plus the improvement the efficiency changes will make in the buyers comfort, convenience and enjoyment of their home. If what you want to do exceeds the ROI plus the utility value increase you deliver, then project isn't worth it to the customer.

Countless examples of this perversion exist. Green energy supply mandates plus tax credits massively pervert the solar energy market. CAFE standards pervert the automobile market along with hybrid vehicle tax credits.

Reply to Rant & But Why

Rant: When I put this up on my blog originally, I put all the parts up simultaneously, so I understand the frustration. There are 4 parts to it, with a 5th coming. The next part talks about the fallacy of low hanging fruit, the third talks about Hard Truths of Home Performance and the 4th finally outlines the program itself. This part is laying groundwork. The idea is revolutionary and will push the boundaries, so time needs to be spent laying groundwork so it isn't rejected out of hand. This is vision casting. Thanks for the comment, though!

But Why: Frankly, I agree. It sucks that markets are perverted, but that is reality.

49 states have efficiency mandates (my state, Ohio, just froze the mandates) siphoning money from utility bills. Politically, these are already in place. Getting anything changed is unlikely - political gridlock is everywhere.

The current programs are screwing things up and hurting the people trying to do HP work. Structure was hard on me, and I personally know 3 energy auditors pushed out of business by utility programs. My competitors dropped the program. A house divided cannot stand, so let's unite it. Let's work with what we've got and go.

One Knob is meant to be easily dialed back over time once it serves its purpose. We'll want the data, to see how the program is performing and be able to rank contractors for performance. Will Schweiger on Long Island has shown he can get client utility data for $100, so it doesn't have to be expensive. One Knob should cost 1/4-1/2 to buy energy savings vs. what happens today, so the money goes further. There are no knots that contractors get tied in. If we have to have programs, this one offers the least incentive perversion possible.

As far as selling projects on ROI, residentially there is no ROI. Real payback numbers will land in the 40-60 year range if you're honest for a comprehensive job. I'm selling projects in this range without incentives.

If you have a politically possible idea to do what you mention, I'm all ears! Please provide a solution that has a likelihood of working. That's what I'm trying to do. Otherwise, it's just whining like I said. I do appreciate the points, though!

reply to but why

A carbon tax might better ameliorate some of the externalities in energy production, like air pollution and the need to keep Navy ships in the Persian Gulf and make nice with the Saudis.

But such a tax is politically impossible. So we encourage people to conserve energy by a subsidizing solar, wind, etc. We discourage gas-guzzlers by imposing CAFE standards. We impose energy efficiency by codes. It's a highly inefficient method, but the alternative of pretending there isn't anything to worry about is unacceptable to some people.

As for regulated utilities, they don't get to complain. They get a guaranteed rate of return in exchange for operating a monopoly. Fairness is irrelevant.

Nate is great!

I think your entire blog series is the best thing ever to hit the incentive world!!!

But why... Why are you posting your rant as but why? Tell us something positive... Utility regulation is not going away, so your whole train of thought is a waste.

Free markets with out over site have never existed and never will. There is ALWAYS A STRONG MAN. So what, do you want to be the strong man?

Tell us the world you prefer but why man...

Incentives

The incentive schemes as described seem to be arrangements for forcing people who have no choice in the matter to give their money to other people who are choosing to improve their properties. Or am I missing something ?

Peter

That's a very interesting way of looking at things. I'm curious as to how people can rebut that description.

Reply to Peter Hastings

The funding from efficiency mandates is there and not super easy to take away, so why not repurpose it to actually do some good? Currently it is counterproductive to the Home Performance industry, pros like me fight the programs. A house divided cannot stand. What has been done for nearly 40 years clearly has failed or HP pros would be living in mansions and there would be a plethora of us. =) It's time to try another tack.

Yes, the utilities have to do it, but as Stephen Sheehy states, they are guaranteed profits on the other side. They are not really private companies, that's the bed they made, so they have to lie in it. Home Performance professionals get the short end of the stick with current design. Do I love the whole thing politically? Heck no. But as they say, politics is the art of the possible. If you have a better option that has a chance, I'm all ears. The rest of the series will be going up soon. If you can't wait, it is on my blog, but I'd rather support GBA.

Clarification

It can, and will, vanish at the stroke of a pen when the next vote-grabber comes along.

When I used the term 'people' I was not referring to utilities but to individuals (the weedy people described in the US Constitution) who pay taxes and utility bills to improve other people's properties. Better by far that they should keep their own money to improve their own property, or not as they choose. Raise code standards for new buildings, but not retro-fits, if you want to improve the efficiency of buildings. And abandon HP incentives altogether. This will broaden the range of choice of buildings (older, cheaper-to-buy, costlier-to-run, less comfortable at one end of the scale and newer, more expensive-to-buy, less expensive-to-run, more comfortable at the other) and revive the Home Performance industry which will be able to quote for and do a wider variety of jobs with no bureaucracy .

peter Hastings

Nate is exactly trying to take on bad government with a better government program. There is no such thing as free markets Peter. Anarchy, chaos, ISIL and caveman, lions and tigers and bears oh my, there is always a strong man in all markets. even when one can't be seen by you the observer.

Better to choose our strong man and influence it than to be run over and fed to the lions by it. Democracy is good and improving it is gooder. Personally I am not for living in ISIL territory or much of Africa or for that matter much of the world.

Nate is great. No anarchy for me thank you. Let's move forward not backward, thank you.

Anarchy and Building Codes

I am suggsting that the democratically-elected government should tackle the question of efficiency in building by creating and enforcing more stringent Building Codes - a better government program. I fail to see how this is to champion anarchy. Similarly, broadening the range of available building qualities is likely to act to increase home ownership - one of the most effective means of giving ordinary people a stake in their neighbourhood and nation. Again, I would argue that this forward-looking action reduces rather than increases the likelihood of anarchy.

One knob incentive

If I buy one widget for $x, I bet I can get most widgets for a lot less if I buy a thousand of them. This is probably also true for energy. Energy companies want to sell energy. If you buy a bunch, they will likely give you a discount. Why would they give you a discount for buying less energy? Possibly for PR. Or the gov't tells them to.

Maybe we can use less energy just to save money. If everyone used a lot less, they will likely reduce the price.

Sorry, just being a little cynical.

Changing Utility Incentive Programs

Nate raises several fundamental issues abut the utility/contractor relationship. As a former utility program manager (I worked for SMUD for 22 years managing new construction, equipment replacement and zero energy building programs), I share Nate's frustration with utility home performance programs. As someone working in the "beast," I saw first hand how poorly planned and executed incentive programs, such as Energy Upgrade California, operated. In critiquing utility incentive programs, however, it's important to keep in mind what drives utility program planners, managers and regulators in designing incentive programs. First and foremost, utility staff and their regulators are obsessed with ensuring that utility programs have positive cost/benefit ratios, or in the parley of the utility world are "cost effective" or provide positive rates of return on ratepayer funds. Of course, what's "cost effective" is open to interpretation, especially with Investor Owned Utilities (IOUs) who aren't eager to part with rate payer funds period. This obsession with cost effectiveness fosters an extremely "risk adverse" culture, especially with utility managers, who are rewarded for increasing returns on ratepayer funds in the IOU world or avoiding political fauxpas in the publicly owned utilities (POUs). Finally, many utility staff and managers have a dislike of contractors, probably based on personal experience (who hasn't had a bad experience with a contractor), and take a paternalistic approach to customers, especially since it's the utility that has to answer to the homeowner when a contractor does a poor job (handling consumer complaints about contractor performance consumed 90% of my time when I managed our equipment replacement program).

So how do you design a home performance program that is market driven, delivers both energy and utility bill savings, and makes homeowners happy? I think Nate has some good ideas but believe that a home performance program needs to be further simplified. We in the efficiency world have become obsessed with trying to determine the energy savings potential of various efficiency improvements. We also spend a lot of time trying to diagnose performance problems when we already know, or should know if you're an experience home performance contractor. In many respects I think that we've forgotten that the major players, the homeowners, want a simple process that shows that they are getting value for what they pay for, and that contractors like to work with simple scopes of work that can be replicated in a predictable fashion.

As part of my work at SMUD, I sponsored six deep energy retrofits (define as achieving 50% reduction in annual energy use, electric and gas), including monitoring the projects upon occupancy for at least one year. You can read about the projects and the results in the attached ACEEE paper I wrote. In brief, the six projects demonstrated that you can achieve dramatic, verifiable energy savings and utility bill savings for the majority of homes (homes built prior to 1980) by installing a home performance "package" of energy efficiency measures - "air tight" attics (in California most HVAC systems are found in the attic), R-38+ attic insulation, fight-sized SEER14+/AFUE 90+ HVAC with tight, R-8 insulated ducts. Ideally, this home performance package would be installed at time of sale to take advantage of the the energy efficient mortgage, a major remodel, or (planned) HVAC replacement. Any competent home performance contractor (GC, HVAC installer or the like) could easily do the work. Furthermore, the package represents a significant "job" and provides an opportunity for the contractor to standardize the work. Finally, the contractor doesn't have to spend a lot of time (and money) doing audits or assessments to prove to the utility that the job will save energy. The utility and its stakeholders - staff, management, regulators, and rate-payers - get easily verifiable, persistent energy savings, especially peak demand savings, the only savings utilities are really interested in, with reduced AC tonnage. Homeowners get real energy bill savings and comfort improvements. Also, homeowners will quickly find out if the contractor has done a good job. The package could also be augmented with other efficiency improvements with utility programs paying bonuses for water heater, appliance and window replacement, wall insulation, and conversion to LED (let's stop with CFLs already) lighting. Packages can also be climate adjusted (the package I described above is California hot climate specific). In short, I think it's time we abandon the current practice of over analyzing home performance., and utilities, through their home performance programs, can help make this happen.

But changing the super tanker that is the utility incentive program world isn't going to be easy. It means re-evaluating the whole utility program paradigm, including abandoning current, very popular equipment replacement only programs, such as CFL or HVAC change-out incentive programs, and you can bet that there are large number of contractors who think the current programs work just fine ( I know. I dealt with quite a few contractors that we're making a pretty penny of our HVAC change out program).

In conclusion, then, utilities not only need to change how they develop and implement their incentive programs, but contractors will also have to change their business practices.

Final note. I need to acknowledge Rick Chitwood and David Jackson of the Redding Electric Utility (serves Redding, California) for introducing me to the idea of home performance packages. Check out their work in the Jan. 2012 ASHRAE Journal.

Anders - Energy Prices and Useage

The price that the consumer pays for energy has two components - the price of the fuel used, either directly or to generate electricity, and the price of providing, maintaining and improving the infrastructure needed to deliver the energy to the consumer. If energy useage drops significantly then the first part of the price drops accordingly. The second does not because of the timescales and costs in decommisioning redundant plant. So the cost to the utility, which it recovers from the consumer, will not fall in the same proportion as the reduction of use. So the cost per BTU or kWh will actually rise. The most economic course of action is to reduce your own use of energy while encouraging everyone else to maximise theirs...

Now that's cynical !

response to Peter

In Maine and many other places, the "utility" is several different entities. One company, here it's Central Maine Power, owns the poles and wires. Other companies own power plants that provide the electricity. Thus, whichever company owns the most redundant generating plant gets hurt if use goes down. That company may not necessarily be able to recover its costs. At least that's my understanding.

Rant

I liked the first post that beautifully described how low cost insulation and sealing jobs were difficult to make a profit on and were difficult to keep crew morale up as they changed locations daily. However this post really adds nothing to the conversation. Hopefully the cliffhanger followup post pours some concrete ideas.

For those who can not wait

http://energysmartohio.com/blog/one-knob-part-4--program-description

None of this seems to have realistic potential to "scale"

Fascinating debate. Grateful to Nate for storming in and shaking things up. At this point, I'm leaning towards Peter Hastings' view that if we're going to have a Program, lets stick with Building Codes. They're VERY imperfect, but they evolve slowly in the right direction (to steal a metaphor: the arc of construction oversight is long, but it bends towards building science.) Moreover, their framework is established in law, and most folks are accustomed to their influence and resigned to their power.

My main concern with One Knob and all other incentive programs is that they have little relevance for the vast swath of people living on incomes lower than average. If they own their homes, there's no money for any sort of improvement. If they don't, the landlord has no incentive to act, since all energy bills are paid by the tenant.

In my midwestern rural town, I'm surrounded by blocks of poorly constructed houses with ill-conceived additions that at best would be difficult and expensive to upgrade. House values are stable but very low--older houses rarely reach six figures. A recent trend towards investing in real estate has led to more and more of my neighbors being tenants, paying rent to a landlord whose margin is very narrow. New roofs and windows are common upgrades, but little else. The landlord has ZERO incentive to change anything. One small house across the street has electric heat bills easily exceeding $1,000 in winter months, split among three tenants.

Not sure how any of these programs would ever scale to include houses like these. How can we bring these improvements to the millions of homes in rural America, not to mention the substandard urban neighborhoods? If the programs are just working for the moneyed class, how is this "working?" I'd be the first to argue that one of the best tools for renewal would be a bulldozer, but then how can we get the market building small, efficient, affordable houses? An honest accounting for the cost of fossil fuels (i.e. a carbon tax) may get us started on this. That's in our national interest as much as a Navy ship in the Persian Gulf.

Response to Andy Chappell-Dick

Andy,

I share your concern -- that most "incentive programs ... have little relevance for the vast swath of people living on incomes lower than average."

The exception is the Weatherization Assistance Progam, a federal program that is now 38 years old. Decade after decade, this program has invested in weatherization work that is (a) demonstrably cost-effective, and (b) targeted at low-income Americans.

The program even provides weatherization services to landlords who can show that their tenants are low-income. While this strikes some observers as odd -- after all, why do landlords deserve these government-subsidized services? -- the results speak for themselves. Low-income tenants get reduced energy bills; our country imports less foreign oil; and carbon emissions are reduced. Over time, the value of the energy saved by this work significantly exceeds the cost of the weatherization work.

Response to Andy Chappell-Dick and Martin Holladay

I understand where you are both coming from, I used to be there. A few points:

1. Low income weatherization, cost effective or not, is 100% government funded. Is that scaleable? Is that going to move the needle on energy independence or climate change?

2. One Knob can work with middle and lower income folks, we have to move to monthly thinking and financing, though. Most households can afford $50-75/mo, especially if it reduces trips to the doctor. With On Bill financing that stays with the house (no affect on equity) and $30-50/mo in energy savings, that's an $11,000 - $17,500 project. Would you agree that's enough to do substantial work to the home?

3. Are current programs scaling? I've argued that we have failed as an industry. HP programs are a joke, but the funding is there TODAY, no need to go through political gridlock to get carbon taxes. As bad as we are doing, isn't it worth trying something radical?

4. Rental properties will remain a problem. There is split incentive. If landlords paid heating costs and could make more on the property because the homes are efficient, that could work. Check out what Dave Robinson and Larry Weingarten are doing. They have found that tenants stay longer and pay more for better places to live. Why focus on this, though, when there are so many other things to fix first?

5. Current programs essentially service higher end clientele anyway, most clients in my insulation contracting business were well over $100K household incomes, so no change from today.

6. How else are we to incentivize high quality work, aside from recognition? Low income weatherization work is OK at best, frankly. The inspectors on Energy Smart jobs (we did 40-50 of them) were stunned at our blower door reductions. No one else really tried. There was tremendous price pressure to do mediocre work. Same thing with private work today which is actually substantially worse because of being less comprehensive.

7. Do you have a better idea?

Response to Nate Adams

Nate,

Q. "Low income weatherization, cost effective or not, is 100% government funded. Is that scalable?"

A. Of course. The only question is whether we have the political will. All low-income weatherization programs have waiting lists; there are plenty of eligible houses waiting for this work.

Q. "Is that going to move the needle on energy independence or climate change?"

A. If you are interested in carbon reductions (rather than comfort improvements that aren't cost-effective), then it clearly makes sense to focus on low-income neighborhoods. The worse the house, the more energy savings are available.

Q. "Are current programs scaling?"

A. No. Carbon taxes would have much more immediate effects. An enlightened government would earmark the revenue gathered by carbon taxes for carbon-reduction programs and measures that softened the blow that the taxes would cause for low-income families.

Q. "Do you have a better idea?"

A. Carbon taxes, as I said, with the tax revenue earmarked for appropriate programs.

Response to Michael Keesee

First off, thanks for engaging and thoughtfully sharing your expertise. I'm glad I touched some nerves for someone who used to work 'inside the beast'. =)

While I've taken a lot of words to describe One Knob, the concept is really simple when it comes to utilities/PUCs, etc. Change what 'cost effectiveness' for utilities means. Put a price on a Negawatt, and pay it. If a project saves energy, pay on projected savings, but track so you can provide accountability for contractors and keep everyone honest.

Why does cost effectiveness in project cost have to matter to the utility? They don't care how homeowners spend their money, they care how much energy is saved from their programs and what that costs. Incentivize energy savings directly and let the chips fall where they may. Risk comes off utility shoulders, and certainty of cost arrives as the market gets better at accurately projecting and delivering energy savings.

Does that get to the root of your cost effectiveness question?

As far as being prescriptive goes - just do this, this, and this - it hasn't gotten us far in the past. Also, have you seen 2 homes that are alike? There is no avoiding going to a home, asking questions, and auditing it to look for problems. Audits don't have to be major science projects, but enough has to be done to find root causes and create a decent work scope.

If we're bothering to go to the home, isn't it better to ask the homeowners what problems they are trying to solve? Most don't care about energy costs. They care about comfort and health, from my experience. If we listen to them, we are more likely to find root causes in an audit and fix them. It's really expensive to get into a client home, why not spend another hour or two there and do more than 'take two of these and call me in the morning'?

I'm thankful you know Rick Chitwood. I haven't met him yet, but I will. I'm friends with Mike MacFarland, who was a major part of the study you mentioned, he commented a lot in part 2 - The Fallacy of Low Hanging Fruit. https://www.greenbuildingadvisor.com/blogs/dept/guest-blogs/low-hanging-fruit-fallacy

Chitwood jobs have the scale One Knob is going for - large enough to gain adequate control over heat, air, and moisture flows and manage them with HVAC. That is not the scale seen today, though. In the comments of the next parts there is discussion of how selling these looks.

In fact, the program design you outlined in your comment looks a great deal like a Chitwood job and One Knob. The incentive for going further later is another Negawatt rebate - get $500 off that wall job if it saves $500 in Negawatts. Prescriptive rebates aren't needed if energy savings are directly incentivized. Does that make sense?

When you say over-analyzing, are you talking about up front? That is where it usually is. Few want to dig into realization rates after jobs because they stink. One Knob aims to measure just as you spoke of - see if the contractor did a good job predicting results and delivering a quality job by tracking results afterwards. This was really tough before, but multiple platforms may be capable of this now - Opower, Energy Savvy, and Tendril come to mind.

BTW that up front analyzing slows jobs down and makes contractors look bad when rebates change, eroding trust. This could be a major factor in the 90% of your time spent dealing with complaints.

I think we're looking for precisely the same thing with ever so slightly different structure. Do you agree? Please be sure to check out the next 2 pieces, 2 more are still to come as well.

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in