ABOUT GREEN LANDSCAPES

A home is approached through its landscape

The surrounding area sets the stage for a home — it’s part of the entire façade — so give the same careful attention to the landscape’s design as you do the home’s. This doesn’t mean a big, labor- and resource-intensive lawn and a couple of maple saplings. A better design would reduce the heating and cooling load of the house, require very little water, avoid wooded areas near the house, and replenish the soil.

Healthy soil provides a long list of benefits, from absorbing rain and snowmelt and channeling water into the ground to encouraging plant growth.

Native plants are relatively maintenance-free, needing little water beyond what’s naturally available. Rain water can be collected from the roof for other gardens. But landscapes begin with soil — what’s there and what you can can make.

A well-orchestrated mix of trees, shrubs, and herbaceous plants is not only beautiful, it also has the potential to augment energy and resource conservation measures that have so carefully been incorporated into the house.

Plants can be more than ornamental landscaping features. Where site conditions allow it, planting vegetables and other edibles pays benefits on many levels. Food is usually fresher and better for you than what’s available in the grocery store, and planting a garden is a satisfying and healthy lifestyle choice.

For mulch, consider newspaper and chipped vegetation from the site. Trees that must be removed during construction can be chipped and used for landscaping mulch. Newspaper, either chopped, shredded or in sheet form, makes an excellent mulch in gardens. It controls weeds and helps to keep soil moist.

MORE ABOUT GREEN LANDSCAPES

Just like any other aspect of building, the best results come from early planning. A professional landscape architect or designer gets you off on the right foot. Start with a thorough site evaluation, checking for:

Native plants

Good landscape design takes advantage of plants that have learned to adapt to local conditions. Native species need the least amount of outside intervention to survive, thus conserving water and reducing or eliminating the use of chemical fertilizers and pesticides. Trees have particular significance because newly planted specimens can take years to mature. Draw a map and identify plant species that seem to be prospering.

Soil

Soil types are rarely uniform on a building site. Pockets of clay, sand, or loam can exist in one locale. Soil alkalinity and acidity also can vary, dictating which types of plantings will thrive in different areas. Noting native plantings provides clues about soil types. Cooperative extension offices, land grant universities, or commercial labs offer soil test services at a reasonable cost. The results can help you avoid soil and plant type mismatches, and years of frustration.

Topography

The lay of the land plays a large role in establishing an appropriate design. A large outcropping or low-lying swale will influence the site’s hydrology and should influence planting choices. Recognizing these areas early on will help identify problems and opportunities. Natural drainage features such as a swale can collect rain and snowmelt, while an ominous outcropping can become a key landscape feature accented by native plants.

Microclimate

Wind, temperature, rain, solar exposure, snowfall, and elevation all contribute to a site’s specific microclimate. The more you know about the site’s weather conditions the better. Historical weather data is available through the National Climatic Data Center, or just ask a neighbor who’s been around for a while.

ABOUT NATIVE PLANTS

Temperature

A major limiting factor in a plant’s ability to survive. You can rule out plants that are obviously inappropriate, given the high and low temperature extremes for your area.

Zones and microclimates

Books, magazines, and plant labels often reference zone ranges, telling the reader where a particular plant will grow and thrive. But keep in mind that zones are just a starting point. They’re very broad and don’t account for local conditions. On any site within any zone, there may be pockets of warm, cool, sunny, shady, dry, or wet areas that, despite an apparent zonal match, would kill a plant that should prosper. Such microclimates may also allow a plant to thrive outside of its listed zone.

Other variables limiting plant selections include: rainfall, soil type and pH, and the amount of direct sunlight the plant would receive.

MORE ABOUT NATIVE PLANTS

Lawns require a staggering amount of upkeep

Lawns are usually a big part of the typical yard. But to get the perfect turf we’ve come to expect, it takes a lot of lawnmower fuel, fertilizer, and time. Lawns also need watering.

Depending on how far you want to take it, there are ways to reduce a lawn’s demands, or replace the lawn all together.

Trees: minutes to remove, years to replace

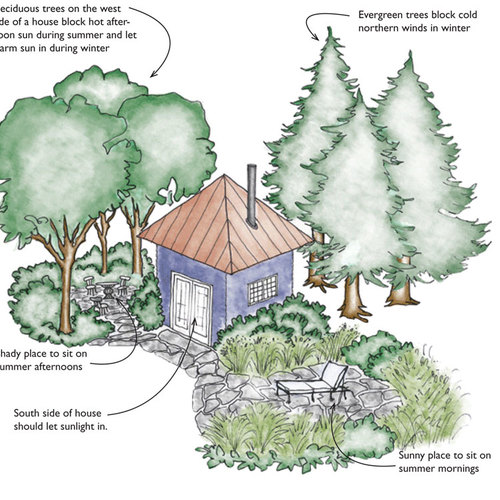

Trees and shrubs can make a house more comfortable in summer and winter.

It may be easier to build on a clear-cut site, but it’s hard to find something that multitasks better than trees. They can block cold winter winds and the hot summer sun, all while making the oxygen we need to breathe. Whether you’re deciding what trees to save or where to plant new ones, there are several things to consider.

It’s easier to build on a cleared job site than a wooded one. But before you cue up the chainsaw or backhoe, consider the long-term benefits of standing trees. They take a long time to reach maturity, when they become large enough to grace a site by blocking wind and providing shade. They’re also expensive to replace. Take time to think about how trees (or the absence of trees) will affect the house when preparing a site for construction, and make decisions accordingly.

On a hot day, it is far more comfortable to rest under the shade of a tree than in the glare of the sun. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) estimates that plantings can reduce cooling costs by 25 percent.

Trees and shrubs make effective windbreaks when they’re planted (or left standing) some distance from the house, lifting wind up and over buildings. The result can be lower energy consumption and greater comfort. Windbreaks can also control drifting snow and create habitat for birds and animals.

About soil

Healthy soil provides a long list of benefits, from absorbing rain and snowmelt, replenishing groundwater sources, and encouraging plant growth. Soil also provides a home for microbes that break down pollutants.

Some soil will inevitably be disturbed during construction; that’s an unfortunate given. The intent should be to do as little permanent damage as possible.

Disturbed and compacted soil can lead to erosion

as well as the failure of existing plants, making it more difficult to restore vegetation later. Encouraging and preserving the symbiotic relationship between soil and plants maintains the health of the soil and decreases loss due to erosion.

Bringing topsoil to the building site from another source creates two potential problems: The site where it is harvested may suffer ill effects; and the imported soil may hold contaminants or undesirable plant species.

It’s often necessary to adjust the grade of a lot to improve drainage and to site the house gracefully among its surroundings. The more extensive and abrupt the grade changes, however, the greater the disturbance to the soil. It’s up to the designer to find the right balance between grade changes that improve the site’s aesthetics and environmental concerns.

About compost

Compost organic waste to create natural fertilizer

One step into the fertilizer department at a retail store can send anyone’s head spinning and wallet wincing. There’s no doubt the numerous and pricey options can be quite overwhelming. One option, however, will naturally feed your lawn and garden for free — compost. Made from organic materials such as lawn clippings, garden debris (weeds, leaves, plant cuttings), and nonmeat kitchen scraps (fruit and vegetable waste, eggshells), compost is a powerful natural fertilizer that has less potential for harmful runoff than the chemical options on the market.

Compost is a great source of nutrients, helps retain soil moisture, aerates and improves soil structure, and encourages vital microbe and insect activity in the soil. Because compost can’t be created overnight (it can take weeks or months for organic material to break down), plan ahead. Have multiple compost piles at various stages in the breakdown process so that one pile develops as another is harvested.

According to the EPA (http://www.epa.gov/compost), yard trimmings and food waste make up nearly one-quarter of the municipal solid-waste stream. Turning them into a useful soil additive is recycling at its very best.

Here are the basics of composting:

•Mix browns and greens. Good compost is a mix of carbon-rich brown material, such as dried leaves and straw, and green, nitrogen-rich materials, such as grass clippings and kitchen scraps. The list of materials that can safely be added to a compost pile, however, is lengthy and includes items like hair, cotton rags, tea bags, shredded newspaper, and even dryer lint (if a family wears only cotton, wool, and linen clothes). Water is a vital part of the recipe too; a pile needs to remain moist to work its magic.

•Avoid adding fats, grease, pet wastes, and meat. These materials break down, but they may contain dangerous pathogens or attract unwanted critters and insects.

•Pick the right spot. Start a compost piles on a dry, level spot that’s not too far from the kitchen if you intend to add kitchen scraps. In dry climates, a nearby source of water is helpful.

•Pile on the organic matter. There are many ways to go about composting. Some people carefully layer and then mix the brown and green materials. Others are less systematic and just add and mix materials into the pile as they become available.

•Turn, turn, turn. If you’re patient, an unturned compost pile will take care of itself. But if you want compost fast, turn the pile with a pitchfork every week or two. If you notice that the pile smells bad, it’s probably not getting enough air, so turn it more often. Compost can be turned regularly until the pile doesn’t seem to generate much heat after it has been tended.

•Use it up. Compost should be ready for use in one to four months. It is great as mulch or when turned into planting beds as a nutrient-rich soil amendment.

If you don’t have space for a compost pile, consider using outdoor tumbling bins or small indoor composting containers. There are many options available for purchase, or you can construct your own.

MORE RESOURCES

Cooperative Extension Service Part of the United States Department of Agriculture, CES is an outgrowth of the country’s original land-grant colleges. Through such efforts as its Master Gardener program, the CES offers practical information about local or regional plants and growing conditions.

* PLANTS Database. The Department of Agriculture also keeps an exhaustive list of native plants in a searchable database at http://plants.usda.gov.

* Reputable local nurseries. Big-box stores with gardening departments may have local experts on staff who can offer good advice, as well as a wide selection of plants. Well-established local nurseries, however, are a more reliable source for information on local plants and growing conditions. Look for plants that actually come from the area (rather than distant nurseries) or have been grown from local seed.

* Regional organizations and programs. There are a number of regional groups and programs that can help you find appropriate plants. These outlets can be found on the Web or by asking around at your local nursery or CES office. Groups like the New England Wild Flower Society (www.newfs.org) are happy to share valuable regional plant information, while programs like Bay-Friendly Gardening (www.stopwaste.org) are becoming more common and are equally valuable resources.

The Sustainable Sites Initiative

National Climatic Data Center (http://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/oa/ncdc.html).

Bird’s-Eye View

Image Credits: Jenifer Benner

Green building begins in the ground

A landscape is more than a bunch of plants arranged to look good. A well-designed landscape can lower heating and cooling costs, reduce stormwater runoff and recharge local aquifers. And it can be good for birds, bees, and neighboring trees.

A well-planned landscape doesn’t need a lot of water, it builds healthy soil, and it doesn’t overrun woods and forests with invasive species. Green landscapes are fed with compost rather than chemical fertilizers, so there’s no poisonous runoff.

Key Materials

Image Credits: Brian Pontolilo/Fine Homebuilding 165

Earth, plants, and trees

Soil. Plants grow well in good soil and die in bad soil. One way to build healthy soil is by composting (see below). Throughout the construction process, be very careful not to compact critical areas of soil.

Deciduous plants. Because they drop their leaves in the fall, deciduous trees and shrubs allow some warming sunlight into the home during the cold days of winter, yet block most of the summer sun’s extreme heat. These plants are most effective when planted on the south and west sides of the house, where the sun shines most intensely.

Evergreens. Trees and shrubs that hold on to their leaves in winter are good choices for the north side of a house because they block cold winter winds. Although evergreens also block sunlight, there isn’t much solar gain from north-facing windows to begin with.

Design Notes

Image Credits: Steve Aitken/Fine Gardening #103

Xeriscaping is the green alternative to the lawn

Xeriscaping, the use of low-growing, drought-tolerant, low-maintenance grasses and plants, is a great alternative to a traditional high-maintenance lawn. we’re used to, including low-growing grasses and other plantings that are better adapted to dry conditions — an approach called xeriscaping. Xeriscapes are also more diverse than lawns, and so are less vulnerable to threats such as insects and disease. They also can require practically no maintenance.

Builder Tips

Image Credits: Daniel Morrison / GreenBuildingAdvisor.com

Fence off trees during construction

Trees can be easily damaged during construction. Trees on or near a building site that are to be left standing should be well-marked. Subcontractors, especially those working with heavy equipment, should be given a tour of the site and clear instructions to stay away from marked trees and other sensitive areas.

Trees often fail after construction because of soil compaction caused by machinery. Keep trees safe by temporarily fencing off their root zones with snow fence or other inexpensive fencing material. Place the fence just byond the tree’s drip-line, or farther. To reduce soil compaction and stress on the tree, be sure the tree gets adequate water (during periods of drought, saturate the soil 8 to 12 inches deep every few weeks) and cover root zones with 3- to 4-inch layers of wood chips.

The Code

Many governments trying to eradicate invasive species

The IRC makes no mention of appropriate plants, trees and shrubs, but federal and state governments have regulations aimed at eradicating non-native invasive species. Many plants now classified as invasive were originally introduced by well-intentioned gardeners looking to improve or diversify their landscapes. A comprehensive list of invasive species can be found at the US Forest Service’s Invasive Species Program Website.

OTHER CONSIDERATIONS

Is irrigation with potable water justifiable?

In some areas of the country — for example, northern New England — lawns can stay green all summer without manual watering. In other regions, however, lawns are routinely irrigated with potable water, a practice that is becoming increasingly difficult to justify—and more expensive—as competition for water intensifies. Where permitted for use by code, gray-water irrigation systems can reduce the burden on municipal water supplies. Collecting and using rainwater is an even easier option.

Las Vegas pays to replace grass

Water conservation is an especially high priority in arid regions. In Las Vegas, the Water Smart Landscapes Program pays homeowners to replace their lawns with plants that don’t need as much water. In just eight years, the program has been responsible for the removal of about six square miles of the green stuff. The city estimates that every square foot of grass replaced with a less water-needy tree or shrub saves 55 gallons of water a year.

To control pests, make chemicals a last resort

Pesticides used to control insects and other pests can pose serious health risks. Instead of making these chemicals the first option, an approach called “integrated pest management” looks at preventive measures first, then resorts to the least hazardous chemicals available should that fail.

According to the Environmental Protection Agency, not every every weed or bug need be eradicated. IPM sets “action thresholds” below which nothing is done, and seeks to identify pests carefully so appropriate decisions can be made about control. A single ant, for instance, isn’t a call to drag out the heavy artillery. Prevention, such as rotating crops and choosing pest-resistant varieties, may head off a problem before it requires the use of chemical pesticides. If chemicals are required, those with the lowest practical toxicity are used. Indiscriminate spraying of non-specific pesticides is, the EPA says, “a last resort.”

DRAWING LIBRARY CONSTRUCTION DETAILS

THE TRUTH ABOUT BIG GREEN LAWNS

According to government estimates, lawnmowers in the United States collectively use 580 million gallons of gasoline a year.

Homeowners apply 67 million pounds of pesticides annually to lawns and in the process poison as many as 70 million birds.

All together, Americans spend about $25 billion on lawn care every year. Homeowners, on average, devote 40 hours a year to cutting the grass.

RULES OF THUMB

Avoid invasive species. Some 85% of the invasive woody plants in the U.S. were originally introduced for landscape or ornamental use. Invasive plants can crowd out native species.

Buy locally. Specifying locally grown plants reduces energy and transportation costs and ensures that plants will thrive in local conditions.

Don’t let plants sit out too long. New plants shouldn’t languish on-site waiting to be planted. If they must be stored, make sure they stay well watered. Heel-in rootballs and provide nutrients as required.

Don’t place plants against the house. Remember that plants too close to the building may encourage insect infestation and can trap moisture, leading to mold or even decay. A good practice is to keep plants at least 18 inches from the foundation wall, not so much when they are originally planted but when they mature. Irrigation spray heads should be directed away from the building.

The Sustainable Sites Initiative

MAKE IT GREENER

Landscapes are more sustainable if the soil is improved to optimize water use (thus minimizing irrigation needs). [Good Soil Is a Sieve and a Sponge, FG110RE, (illustration by M. Lucas – FG staff)]

GREEN POINTS

LEED for Homes Anything you do outdoors will generally give you greater bang for “green buck” than anything you do in the structure. The easiest to earn are often those related to landscape. These include SS2 (Sustainable Sites) — up to 7 points, SS3 — 1 point, SS4 — up to 7 points, and WE2 (Water Efficiency) — up to 4 points. Up to 4 Innovation points can be earned for exemplary performance with regard to these credits.

NGBS/ICC-700 A variety of credits also are available for landscaping in the National Green Building Standard.

2 Comments

news pieces

it was helpful

composting

Helpful and interesting. Glad i found this site.

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in