Several recent articles in popular periodicals suggest that many modern educational and commercial buildings need better ventilation systems. Of course, most green building experts welcome this increased focus on indoor ventilation (even though they lament the fact that the focus is a result of a worldwide pandemic). Green builders have been preaching for years on the need to “build tight and ventilate right.”

Moreover, many green building researchers have reported for years that current code requirements for indoor ventilation are rarely implemented properly. (See, for example, these GBA articles: “More Bad News on Ventilation System Effectiveness”; “Broken Ventilation Equipment Goes Unnoticed for Years”; and “Is Your Ventilation System Working?”)

While some of the issues raised in the recent (post-pandemic) articles published in the popular press—especially worries about the effectiveness of school ventilation systems—have been discussed for decades, new elements are emerging in debates about indoor ventilation. One new element is a call for increased ventilation rates. Another new element is the suggestion that better indoor ventilation could not only reduce Covid transmission, it might be able to reduce the transmission of seasonal flu and the common cold, as well as other airborne viruses. Those who argue in favor of this last point imply that many people living in industrialized countries have been accepting bad indoor air for too long, and that our society’s inability to provide adequate indoor ventilation has resulted in poor health outcomes that we all take for granted—but shouldn’t.

What we know

Some of these opinions remain to be supported by good data. That said, almost all ventilation and public health experts agree on some basic facts:

Weekly Newsletter

Get building science and energy efficiency advice, plus special offers, in your inbox.

This article is only available to GBA Prime Members

Sign up for a free trial and get instant access to this article as well as GBA’s complete library of premium articles and construction details.

Start Free TrialAlready a member? Log in

4 Comments

Thank you for this helpful summary of a complex issue.

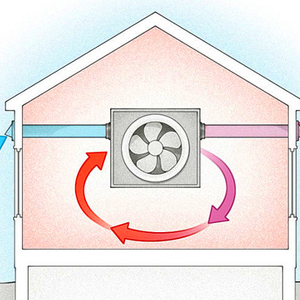

In some circumstances, an effective ventilation strategy may require thinking about both quantity and quality— the rate and the path of flow. “Displacement ventilation” is interesting this context. This approach involves supplying air at low velocity down low in a room and extracting up near the ceiling. In this way the stack effect can help purge stale air before contaminants like CO2 or viral aerosols are inhaled. So it may be possible in some circumstances to have relatively lower flow rates and higher quality air.

The economics are also interesting. As with so many things, you can make an avoided cost argument in favor of spending money on indoor air quality by simply noting that the savings pay for the improvement. Experts have noted that we are already paying for better air, we’re just spending on the wrong side of the equation—hidden costs like low productivity and poor health amount to much more than the cost of the fix. More here:

https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/news/press-releases/office-air-quality-may-affect-employees-cognition-productivity/

Norman,

Thanks for the link to the Harvard School of Public Health press release. The study discussed in the press release is one more in a cluster of studies that show the importance of good ventilation for cognition and alertness.

As you point out, the cost of the energy penalty associated with increased ventilation should be balanced against the possibility of improved productivity and employee health.

Interesting piece. The suggestion made by Corsi, the engineer from California, to disable the ventilation controls is out there. The average classroom is probably occupied 15% of the time at best. In my back of the envelope calculation, ventilating a classroom at 3 ACH 24/7 could double or triple (in a cold climate) the energy load. Most schools are already super energy-intensive and wasteful. Yes, we need good air quality, but for the sake of the climate -and school budgets- we are going to need engineers who are a little more thoughtful than this.

Vivian,

When I heard Richard Corsi's recommendations on a report broadcast on National Public Radio, and later read his recommendations in an article in the New York Times, I had the same reaction you did. When determining ventilation rates, "the higher the better" isn't engineering. It's a meaningless statement.

Log in or become a member to post a comment.

Sign up Log in