If a tree falls in the forest and no one is around to hear it, does it make a sound?

This philosophical exercise should be familiar to everyone. It is, of course, a question of perception. If there are no ears present, how can sound exist? Then again, the absence of ears doesn’t render the laws of physics moot. You may think the answer is obvious, but the alternative answer is as well. The same rules could well apply to energy and building codes. If a state adopts a comparatively stringent code and there is no one to enforce it, does it have an impact?

New codes in the Pine Tree State

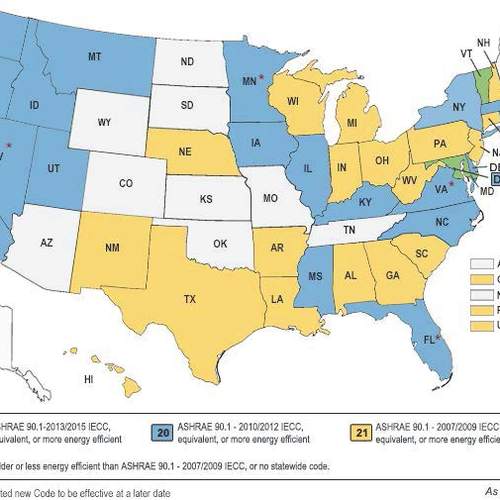

In 2020, the State of Maine (pop. 1.3 million) required the Maine Uniform Building and Energy Code (MUBEC) Board to adopt the 2015 International Energy Conservation Code (IECC) statewide, which went into effect for every town—all 482 incorporated municipalities spread across 16 counties—the following year. The State also mandated the creation of Maine’s first stretch code, which the MUBEC Board designated as an unamended 2021 IECC. (The DOE estimates the 2021 code achieves up to 15% greater efficiencies than the 2015 version.)

Also in 2020, Portland—Maine’s largest city (pop. 68,000+)—passed its own “Green New Deal” citizens referendum, designed to increase affordable housing stock and implement greater efficiencies for new construction. (The policy has received pushback from some large builders for allegedly slowing down or altogether squashing important development, like a planned emergency homeless shelter in 2022 that never got built.) In tandem with the Green New Deal, Portland and neighboring South Portland officially adopted the state’s stretch energy code, which went into effect July 2021 and April 2022, respectively. And just last summer, the small coastal town of Freeport (pop. 1817), home to L.L. Bean, became the third municipality in the state to adopt the stretch code.

On the surface, this is all encouraging news. And by most accounts, enforcement of the stretch code has thus far been successful in the larger cities. Portland and South Portland have also adopted a Net-Zero Energy Appendix that was included in the Green New Deal policy, which stipulates that new buildings must produce as much energy as they consume. This would certainly explain why some developers have elected to build elsewhere, and elsewhere may be the problem. Because as it turns out, in a largely rural state made up of small towns and villages, where even the enforcement of building permits is lax to nonexistent, getting builders and homeowners to comply with complex energy codes isn’t so cut and dry.

According to Randall Poulton, a retired construction professional and former board member with MUBEC and the Associated General Contractors (AGC) of Maine, “Adoption is only the first step. Step two is educating the design, construction, and enforcement industry. Step three is enforcing what was adopted. A three-legged stool is only useful when all three legs are attached.”

Maine’s small-town challenge

While the base code does apply to all of Maine, and builders are fully expected to build to that standard, actual enforcement of MUBEC is strictly optional in towns with a population up to 4000. By the numbers, that means less than 20% of all municipalities in the state (representing about 68% of the population) are legally obliged to enforce compliance with MUBEC, or the stretch code as an optional appendix.

That is a lot of wiggle room, and frankly, 4000 is a pretty high benchmark in a state that is majority small town but comparatively rich in tourism, averaging more than 15 million visitors per year. Maine’s state building official Paul Demers considers 4000 a fair number in terms of what can reasonably be managed by the limited personnel in place. Code enforcement officers are spread thin as it is, he says, and don’t have the time “to study what they need to know and enforce what they need to enforce. That cut-off makes sense. But in lieu of that, there should be some regionalization that covers the consumer.”

Demers, who also sat on the 2024 IECC Development Committee for commercial buildings, would much prefer a uniform code be in place. Short of that, his chief concern is with the lack of widespread adoption and enforcement of the 2015 IECC base code, and as an aside, how the stretch code may be exacerbating the issue.

“I highly encourage building above code and having a stretch code as a guideline,” Demers says. Builders then have a clear roadmap for meeting any high-efficiency expectations that their clients bring forth. “Give it as a guideline, but don’t mandate it. There’s nothing that prohibits you from using it if you want to, but don’t make somebody who can’t afford it do it.”

On the other end of that spectrum is, once again, the question of enforcement. If developers and builders are being held to a stringent performance standard in one of Maine’s two dozen cities, for instance (or an even higher standard in Portland, South Portland, and Freeport), but many of those same builders can operate with impunity in approximately 350 other towns, then the viability of the entire system is very much in question. “It’s great to adopt building codes,” Poulton says, “but without education and enforcement, the codes are just more paper gathering dust in Augusta. Where I live, in Winterport, we don’t even have building permits!”

To code or not to code (revisited)

Last summer I wrote about the ongoing development of the 2024 IECC and, incidentally, some of the hostility directed at the 2021 IECC by National Association of Home Builders (NAHB) Chairwoman Alicia Huey. In the article’s ensuing comments, GBA expert member and Pretty Good House co-author Michael Maines said, “Until low-carbon building practices reach the mainstream, I would like to see codes stay where they are; despite good intentions, this is the absolute worst time in human history to dump a lot more carbon into the atmosphere. We can more easily accommodate lower-performing new homes that have low levels of embodied carbon than we can high-performance homes full of foam.”

Maines’s comment feeds into a different part of this discussion that raises the question: Are we moving too fast on energy codes and, consequently, playing fast and loose with people’s livelihoods?

This is a fair question, and one particularly apt within the State of Maine. If small towns with a population <4000 are intent on maintaining a libertarian approach to code enforcement, that’s their prerogative, so long as that approach doesn’t give way to sheer negligence. There is also the prevailing issue, as Maines suggests, of building for operational efficiency at the cost of releasing a bunch of upfront emissions. Reconciling those things is certainly possible, but it’s also lot harder to achieve when enforcement practices are inconsistent on a wide scale.

In 2022, Kaplan Thompson Architects co-founder Jesse Thompson participated in a webinar hosted by One Climate Future. In the discussion, Thompson remarked that organizations like the ICC are “under huge pressure” to refrain from moving the needle too quickly on codes and performance standards, lest they disrupt the economy. Clearly, some reputable experts like Maines would prefer for regulations to slow down so that markets in the home space have a chance to catch up. Others see steady and progressive action as the solution.

“Regulation is the way we are going to change a lot of things,” Thompson said. “If you’re building a building to sell it, your incentives are not to build for energy efficiency unless the customer asks for it, and it’s really hard to a be customer of a building. You rely on other people like building inspectors, and you rely on cities to have good codes.”

_______________________________________________________________________

Justin R. Wolf is a Maine-based writer who covers green building trends and energy policy.

Weekly Newsletter

Get building science and energy efficiency advice, plus special offers, in your inbox.

7 Comments

Good timing; today I'm working on a design for a renovation/addition in South Portland and hadn't yet done the research to understand that they are now on the stretch code. Not that I find it challenging to meet the 2021 IECC using materials and assemblies with low levels of embodied carbon, but from what I have gathered from online forums, builders and architects all over the US can't seem to find a way to meet the requirements without using mountains of spray foam. Even the newer, HFO-blown spray foam has significantly higher levels of embodied carbon than other types of insulation, and other downsides as well.

Good for Maine !! Maine likely does not have the production builder resistance that states with larger population centers have. Saw this resistance in the 2000's here in MN, there is always an opposing force to using less fossil fuel. The opportunity for small and midsize builders is to build better, something the big builders can't and will not do. Land control becomes the issue so be prepared to rework existing homes and neighborhoods.

Doug

Michael,

To circle back on Justin's comments in the article relating to costs and livelihoods: what cost percentage increase (if any) do you estimate your using materials and assemblies with low levels of embodied carbon to meet 2021 IECC code is compared to builders that use spray foam or other high carbon materials? Do you think there's a cost factor driving here, or simply a lack of education?

I'm not sure as I don't give builders the option, and it depends on the design--if you keep designing the structure as if it were 1960, spray foam can be the only reasonable way to insulate. Using double-stud walls and attics with raised heel trusses with cellulose or wood-fiber insulation is my standard detail and not very difficult to do.

There is probably a small cost upcharge to building double stud walls, but there are advantages of avoiding spray foam other than environmental impact. On low-budget jobs the cost may be enough to matter. On mid- to high-budget jobs, it's architects, builders and owners who simply don't care about their environmental impact (or actively enjoy polluting), not wanting to learn and train new techniques, and making things as easy on themselves as possible.

I took the same line when I started building in Minneapolis/St. Paul in 1988. I was approached to build a high end house for the Parade Of Homes. I said I would but it must meet my energy design criteria, minimum R25 wall, R70 attic and R20 basement walls. Vapor barrier was continuous with heat recovery ventilation and Lennox Pulse heating. Got to know the building inspector along the way and he told me this was the best built house in the city.

Doug

Wow, those are some serious specs for 1988! Still "Pretty Good" today.

Built a couple of single plate 2x8 wall with staggered studs after the 1988 house. Used Teno 8 mil in those days so we had quite the warm side air barrier. Had the lead building official stop by for my insulation inspection for one of the homes. Air barrier was continuous with Tremco sealant everywhere, he walked in the door, looked around and just said "outstanding". We energy builders do not get much praise from anyone, this seal of approval I remember.

Doug

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in