Image Credit: Riverview Homes via Wikimedia

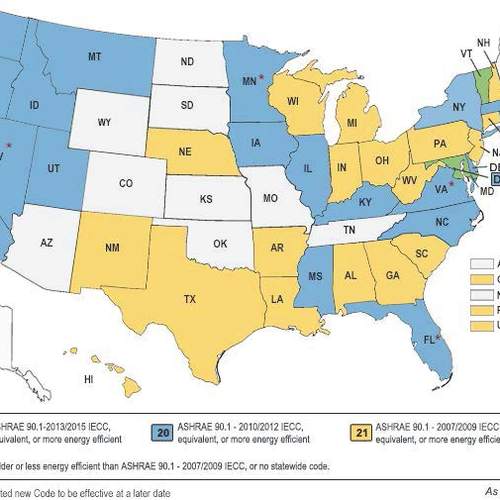

Image Credit: Riverview Homes via Wikimedia The new energy code for manufactured housing would establish four climate zones in the U.S., mostly along state lines. As in the International Energy Conservation Code, the proposed standards for manufactured housing set minimums for insulation and window U-values for each climate zone.

New efficiency rules proposed for the nation’s manufactured housing industry would reduce energy consumption by an estimated 27% and save homeowners thousands of dollars, according to a member of the committee that helped draft the plan.

Writing at the website of the American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy, senior policy analyst Lowell Ungar says the new Department of Energy standard has been drafted and will be open for public comment through August 16. That follows years of foot-dragging and missed deadlines for a rewrite of the so-called HUD Code, the efficiency rules developed by the Department of Housing and Urban Development.

Energy requirements for manufactured housing, once commonly called mobile homes, are handled differently than they are for other kinds of housing. It’s up to individual jurisdictions to adopt an energy code that covers site-built and modular houses. New versions of the International Energy Conservation Code became available in 2012 and 2015, with states free to choose whatever version they like, or go without. But because manufactured housing can be delivered across state lines, the HUD Code spells out requirements for manufactured housing in all states, Ungar explains.

More than 70,000 units of manufactured housing were built in 2015. That’s as many single-family homes as were built in any state in the country except Texas. States with the most manufactured housing — Florida, California, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia — all have adopted energy codes that are at least as stringent as the 2009 IECC, but the HUD Code hasn’t changed very much in more than 20 years.

This wrinkle has left occupants of manufactured homes, whose median family income is about $30,000, paying an average of $1,800 a year in energy costs — which, according to Ungar, is about twice the national average on a per-square-foot basis.

“Many of them spend more on their energy bills than on home loans,” he says.

What the new rules do

According to Ungar, it’s taken a long time to develop the new standard. Congress directed the Department of Energy to set new requirements for manufactured housing in 2007, but it wasn’t until October 2014 that a committee working on the plan came to terms. Another year passed before DOE submitted the plan for review with the Office of Management and Budget Review. The draft, covering 172 pages, was released in June.

The starting point for the manufactured housing working group was the 2015 IECC, but the group made a number of changes. Developers began by reducing the number of climate zones from eight to four, mostly but not always along state lines, to simplify compliance.

DOE decided that allowing manufacturers to choose either a prescriptive or performance-based path to compliance “would realize cost-effective energy savings for homeowners while providing for flexibility within the manufactured housing industry.”

The chart (below) details the minimum requirements for insulation in the floor, exterior walls, and roof, along with maximum U-factors for skylights and windows.

A separate section allows compliance when the building meets an overall thermal envelope standard, called the Uo value. This value varies by climate zone, and whether the house is a single-section or multi-section. Uo values range from 0.087 to 0.059 for single units, and from 0.084 to 0.056 for multi-section homes.

The proposed rule does not include a specific airtightness requirement expressed in air changes per hour, although it does spell out construction techniques to minimize air leaks. On that point, the document notes, “The [manufactured housing] working group recommended sealing requirements that would ensure that a home can be tightly sealed with techniques that can be visually inspected, thus minimizing the compliance burden on manufacturers. The MH working group also recommended the adoption of air leakage sealing requirements designed to achieve an overall air exchange rate of 5 ACH within a manufactured home.”

The rule also “did not address the options for systems of compliance and enforcement, and DOE has not included proposed compliances and enforcement provisions in this proposed rule,” the document says.

Effects on the industry

DOE estimates that the changes will reduce energy consumption in manufactured housing by 27% when compared with the current HUD Code, an average lifetime savings for homeowners of nearly $4,000, Ungar says. Nationally, the cumulative energy savings would amount to 2.3 quadrillion BTU, the amount of energy that all the houses in New York and Florida use in one year.

Costs would go up for both single-section and multi-section manufactured homes, the proposal says, with price increases varying by climate zone. In Climate Zone 1 (the warmest part of the country), costs for a single-wide would rise by $2,422, or 5.3%. In Climate Zone 4, the increase would be $2,208, or 4.8%. For multi-section structures, price increases would range from $3,748 to $2,877.

Annual energy savings would range from $345 for a single-wide to $490 for multi-section, with a simple payback of about 7 years.

The environmental benefits from energy conservation would be considerable, adding up to 60 million metric tons of carbon dioxide for single-wides, and another 98 million metric tons for mutli-sections.

According to the Manufactured Housing Institute, the average sales price of a new manufactured home, including installation but not the lot, was $68,000 in 2015, or about $48 per square foot. Single-wides averaged $45,600, multi-section houses $86,700. Manufactured housing accounted for about 9% of total single-family housing starts in 2015.

Improving the energy performance of these houses will make them less expensive to own, but the impact of higher purchase costs was clearly on the minds of some people who filed comments with the DOE.

“One commenter stated that increases in the purchase price of manufactured homes due to energy conservation improvements could raise issues of affordability without government subsidies or incentives,” the document says. “Another commenter similarly stated that raising energy conservation standards too quickly could impact manufacturers’ ability to modify their in-plant production and site-installation processes and procedures.”

Despite the risks, DOE sees big benefits from the changes.

“Establishing robust energy conservation requirements for manufactured homes would result in the dual benefit of substantially reducing manufactured home energy use and easing the financial burden on owners of manufactured homes in meeting their monthly utility expenses,” the proposal’s introduction says. “Improved energy conservation standards are expected to provide nationwide benefits of reducing utility energy production levels that would in turn reduce greenhouse gas emissions and other air pollutants.”

Weekly Newsletter

Get building science and energy efficiency advice, plus special offers, in your inbox.

0 Comments

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in