Image Credit: Robert Riversong

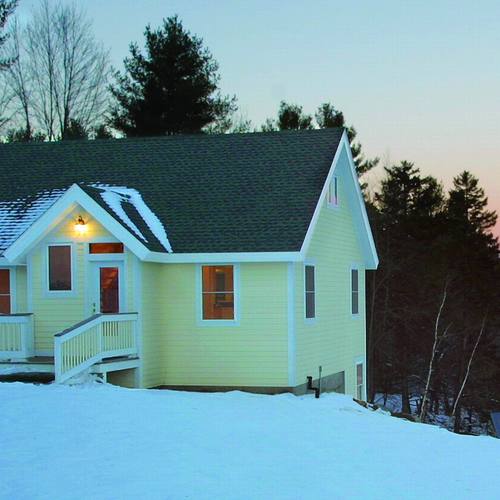

Image Credit: Robert Riversong A welcoming roof protects the mudroom entry in the northwest corner of the house.

Image Credit: Robert Riversong Access to the unconditioned attic is via a weatherstripped "hay-loft" door in the east-facing gable; that means that the home's insulated ceiling is not interrupted by an access hatch.

Image Credit: Robert Riversong The walls are framed with 12-in.-thick modified Larsen trusses. The house has no wall sheathing; Typar was installed over the framing, followed by spruce novelty drop siding. The walls are braced with metal T-bracing straps.

Image Credit: Robert Riversong The 12-in.-deep window rough openings are lined with plywood.

Image Credit: Robert Riversong The durable 2-in.-deep ventilation channels near the eaves were fabribricated on site from panels of hardboard.

Image Credit: Robert Riversong A frost-protected shallow foundation requires less excavation and a smaller volume of concrete than a conventional foundation. The dining room includes a wood stove.

Image Credit: Robert Riversong The home's second floor is designed to accommodate boarders.

This comfortable, practical, and ecologically responsible house was also affordable, thanks to a crew combining skilled workers and trainees, a sweat equity contribution from the owner, and “time & materials” billing by the builder

By Robert Riversong

I was hired to design and build a home for a Vermont land owner who wanted a house that would be affordable to build, affordable to live in, as green as possible, accessible as she aged, and able to generate rental income.

We collaborated on the design, planning, permitting, and site work. We created a floor plan that would place all necessary living spaces on the first floor. The second floor has a great room, two additional bedrooms, and a second full bath so that she could rent space to boarders.

To improve the home’s accessibility, the entry doors have low-profile sills. The interior doors are 2′-10″ wide. The curbless tiled shower, soaking tub, and downstairs toilet all have grab bars.

The site was perfect for a shallow foundation

The client’s land was on both sides of the street. She decided to subdivide the section opposite her existing log house to create a second building lot. The level, grassy site had just enough room for a deep well, an in-ground septic system, the footprint of a house, a (future) two-car detached garage/apartment, and a 16-ft. connecting breezeway with a pressure-treated deck.

The well-drained ground is gravel to a depth of 6 ft., underlain by sand. The soil would allow a shallow foundation with no need for sub-soil drainage. A sub-slab radon vent mitigates any potential for soil gas entry, and underground drains divert rainwater to nearby woods.

Passive solar requires an integrated design approach

An initial set of plans and elevations, created by another designer, were shelved for a holistic approach to energy efficiency which optimized the free available heat of the sun. The home has a simple rectangular footprint (with an entry/mudroom wing). It is orientated east-west, with the south façade facing an open, unobstructed field. An open south-side floor plan, a thermal mass floor, a tight very well insulated thermal envelope, sufficient but not excessive south glazing, and engineered south overhangs on both levels are all integrated into a home that can be heated with 1½ cord of firewood.

Building “green”

Except for the weight, building with fresh-sawn green wood is a pleasure in many ways. It cuts like butter. Nails almost fly into it – even the 20d galvanized monsters that were required for the full-dimension lumber – and it’s straight as an arrow. Once it’s secured in the frame, it dries in the sun and air and stays straight.

Because I don’t sheath my walls, they are fully exposed to the drying summer conditions. By the time the frame is wrapped and sided, the moisture content of the framing is less than kiln-dried lumber.

A moisture-tolerant structure

With a caulked and gasketed frame, Lessco polypan electrical box surrounds, careful sealing of all mechanical chases, and no penetrations in the upstairs ceiling except the plumbing stack (sealed with roof flashing) and the chimney (fire-stopped), the house is more than tight enough to prevent air-borne moisture from exfiltrating. Gasketed “hay-loft” doors allow service access to the major and minor attics above the thermal envelope.

To keep moisture where it belongs, we back-primed all exterior wood and paid careful attention to flashing. The site was carefully graded to keep water away from the foundation, and the design includes generous roof overhangs and seamless aluminum gutters connected to underground drains.

The walls have no sheathing, and the softwood siding is finished with a latex solid-color stain — details that make the exterior skin highly vapor-permeable. The only vapor retarder on the inside skin is 1-perm vapor retarder primer. The cellulose insulation and wood framing are both highly hygroscopic; in other words, they can safely store and release the minor quantities of moisture that any house — no matter how tight — can expect to experience over its lifetime.

Keeping water out is only half the equation for a durable structure — allowing the envelope to store moisture and dry in both directions as the seasons change is the other, and often neglected, half. The moisture storage ability of natural materials also helps to buffer the indoor relative humidity, just as thermal mass helps to buffer indoor temperature variations.

Optimizing the thermal envelope

The modified Larsen Truss wall system, one that I developed during 30 years of building superinsulated homes and additions, allows high levels of thermal insulation with the least amount of thermal bridging of any system except SIPS or structural strawbale.

The wall can be made to any thickness. Twenty years ago, when 2×4 walls were still standard, I determined that 12 in. was appropriate. This depth offers deep, inset windows with usable sills, a continuous thermal blanket interrupted only by doors and windows, and a structure that remains cool all summer, warm in winter, and uncommonly quiet.

Borate-treated cellulose is not only composed of almost entirely recycled material, but is also highly resistant to fire, insects, rodents and mold. It’s also completely non-toxic to humans. By designing flat ceilings, the amount of attic insulation is limited only by the budget and the distance between ceiling joists and the rafters at the eaves.

By using independent let-in ledgers for each, I can maintain full 20 in. insulation depth to the outer perimeter and a 2 in. ventilation channel (site-built of overstock hardboard). Having reviewed nearly all the research on venting of roof assemblies, I remain adamant about a well-ventilated roof to avoid winter ice dams, keep the attic cool in summer, extend shingle life, and evacuate any moisture that does find its way into that space. I use the only ventilation system that’s been independently proven to be efficient and reliable: continuous soffit vents and continuous wind-baffled ridge vents with no obstruction in any rafter bay.

BSC_R-value_recommendations.jpg

Weekly Newsletter

Get building science and energy efficiency advice, plus special offers, in your inbox.

Lessons Learned

Put everything in writing

I've made it a practice to draft a memorandum of understanding (MOU) at the start of any major building project, to make sure that initial agreements are not later misconstrued, and that each party understands their respective roles and responsibilities. I include a mediation clause, in the event of “irreconcilable differences.”

I had agreed to design and build this home because the client stated her intention to grow old in it and had somewhat limited resources. Because I work for a very fair hourly wage, pass on my material costs without markup, and don't charge for overhead or profit, I can build a house like this for as little as $100/sq. ft. in a market in which ordinary custom homes start at $150/sq. ft. I'm willing to put in a personal subsidy for someone with an authentic need for housing and in order to create another example of a truly “green” home.

So I was surprised and disappointed to learn that the house was put on the market less than one year after it was built. If I were to engage in such a project again, I would require an equity-sharing agreement to recover my subsidy if the house were to change ownership within ten years. The silver lining, perhaps, is that dozens of sustainable building students were able to tour the house during and after construction, it's received some attention on the Web and in the building science community, and the young couple who now own it are thrilled with its performance.

General Specs and Team

| Location: | Warren, VT |

|---|---|

| Bedrooms: | 3 |

| Bathrooms: | 2 |

| Living Space: | 1922 |

| Cost: | 105 |

Builder: Riversong HouseWright Home performance consultant: Efficiency Vermont Insulation contractors: Riversong HouseWright, with help from Bill Hulstrunk of National Fiber

Construction

Foundation: Slab placed inside of a frost-protected shallow grade beam

Underslab insulation: Horizontal R-10 XPS under entire slab and vertical R-10 at slab edge

Foundation perimeter insulation: Vertical R-10 XPS at exterior of foundation and 12" of R-10 horizontal wing insulation

Walls: Inner load-bearing wall is rough-sawn 2x4s, 24" o.c.; platform-framed first story, balloon-framed second story with let-in wooden ledgers for ceiling joists and rafters. Outer wall: parallel-truss chords of rough-sawn 2x3 extending from sill to rafter tails, gusseted to studs with rough-sawn 1x4s.

Wall bracing: Let-in metal T-bracing (Simpson TWB)

Rough openings: ½" CDX window & door boxes; Tremco acoustical sealant or EPDM gaskets used for air sealing

Wall insulation: R-45 dense-packed cellulose

Siding: Pre-finished spruce novelty drop siding over Typar

Exterior trim: rough, band-sawn 1x boards

Ceiling insulation: R-68 cellulose

Roof framing: rough-sawn 2x10 rafters

Roof sheathing: rough 1" pine board sheathing

Roofing: Laminated asphalt shingles

Windows: Pella Proline aluminum-clad wood windows (double-hungs and casements) with double-pane low-E² glazing (U-factor: 0.32, SHGC: 0.31)

Energy

Space heating: Triangle Tube Prestige 94% AFUE 30,000-110,000 Btu/hr modulating condensing direct-vent boiler with outside reset; wood stove with ducted outdoor combustion air, vented to a masonry chimney.

Heat distribution: in-floor hydronic (1st floor: tubing embedded in slab; 2nd floor: PEX tubing suspended 2" under subfloor with bubble-foil radiant barrier).

Domestic hot water:: Triangle Tube Smart 40 indirect tank

Appliances and lighting: Energy Star appliances and hard-wired CFLs throughout

Energy Specs

HERS rating: 46

Passive solar design features: Oriented for passive solar heat gain; solar gain satisfies an estimated 28% of the home's heat load.

Blower-door test results: 3 ACH @ 50 Pa with air inlets open; 2.13 ACH @ 50 Pa with air inlets closed.

HERS estimated energy use: 42.8 MMBtu heat, 15.6 MMBtu hot water, 19.4 MMBtu lights & appliances.

HERS estimated annual energy cost: $2,418

Actual energy use (Nov. 2009 – Mar. 2010): 1 cord firewood, 145 gallons propane, 200 kWh/month electricity. (Estimated annual energy cost, extrapolated from winter use: $1,563.)

Water Efficiency

● Efficient front-loading washing machine

● Low-flow shower heads

● 1.6 gpf toilets

● No dishwasher

Indoor Air Quality

● Low-VOC paints and finishes

● Solid pine cabinetry

● Softwood, tile, and concrete floors

● Borate-treated cellulose insulation

● Operable windows designed for effective cross-ventilation

Mechanical ventilation system: Exhaust-only ventilation with timed Panasonic bath fans and Airlet 100 make-up inlets

Green Materials and Resource Efficiency

● Minimal site disruption (excavation only 12" deep)

● Minimal use of concrete (10" x 20" grade beam and slab)

● All concrete form boards re-used in house framing

● Local, rough-sawn, green hemlock lumber

● Local, rough-sawn exterior hemlock trim

● Builder-felled pine trees milled into boards for 2nd floor and roof decks

● Exposed interior load-bearing timbers felled and milled within 5 miles

● Negligible engineered lumber (plywood window boxes)

● Fewer board feet of lumber than a standard 2x6 house, but with 12" walls

● Tinted slab as finished floor

31 Comments

A Clarification

I realize I had written "deep inset windows", by which I meant from an interior perspective - not the "innies" (as opposed to "outies", which is what I employed) that are sometimes discussed with thick-wall houses.

As another cost-effective and aesthetically-pleasing measure, I used drywall returns on at least the upper three sides of each window and door box, with 3/4" bullnosed corner bead for a pleasantly eased transition. The double-hung windows on the south half of the house have yellow pine sills, the east double-mulled window in the living room has a yellow pine window seat that hinges open for storage, the kitchen and bath casements have tiled sills, and the rest of the casements as well as the full-height fixed units on the 1st floor south have 4-sided drywall returns for maximizing diffuse reflected light.

Lessons learned: apples to oranges nad resale value

Hi Robert,

I appreciated the point you made in your lessons learned about the homeowner unexpectedly flipping the property on you as you had made sacrifices on your part to make the property as affordable as possible. I assume the homeowner profited handsomely from the sale?

It reminded of the argument that gets tossed back at me whenever I advocate for Energy Efficient buildings; "Building an energy efficient house costs X% more". (X being some arbitrary value)

It's a ridiculous argument because your not really comparing apples to apples. An energy efficient house (building) reduces the exposure of the owner to volatile energy prices and it's a more comfortable house to live in. But I am preaching to the converted here.

What your lessons learned specifically brought to mind was that people complain that energy efficient houses cost more but that the reality is most homes are built speculatively to maximize profit at resale. That speculative profit taking could have been put to better use building energy efficient homes.

For most people buying a home, even a relatively new one, a good portion of the purchase price is "appreciation". Often no real beneficial feature was added to the home. It just appreciated! And people pay a premium for that? I know you can't remove the speculation from the industry but it suggests that their is considerably more leeway, in terms of capital, to build homes to a higher energy efficient standard.

Cheers,

Andrew

Response to Andrew

The house cost about $203,000 to build, including engineering & permits, site work, well and septic, and fixtures and appliances. I don't know what it sold for but the asking price was $321,000. This, of course, included the 1.3 A site which might have had a market value of $50,000 (since it's near the Sugarbush ski resort) but was already owned by the client as part of her original house lot (for which I'm sure she paid very little).

When I say that I had a personal "subsidy" in the home, that is only in relation to what I could have charged for markup/profit if I had operated as a conventional builder. But, for deeply-held philosophical reasons, I don't charge for any value that I haven't created and I charge what I feel is a fair hourly fee for my time and tools and experience (which is always below market rates).

The "appreciation" that has been part of the American dream of home ownership is driven by two factors. One is speculation, or treating shelter as a commodity rather than a basic human necessity. This is false appreciation, since it has no substantive value (like the difference between the Main Street economy and the Wall Street casino). The other engine of real estate appreciation is public investment in infrastructure: including roads, schools, sewer and water systems, parks and recreation, and public safety. This appreciation rightfully belongs to the public but almost always ends up in private pockets.

There is, in fact, a way to both remove speculation from the housing market and return real appreciation to the community which created it. In 1960, two visionaries created the Community Land Trust (CLT) model as a uniquely American model of ownership. They determined that the three foundational elements of the American Dream were equity, legacy, and security. People used to dream about owning their own home so that they could keep the value that they built, pass on the homestead to their children, and have a place to live which was safe from seizure or eviction.

So Ralph Borsodi and Bob Swann - with inspiration from Henry George (the most influential economist in America who nobody remembers today), the Native American notion of land stewardship, the Israeli collective kibbutz movement, and the Gandhian Gramdan (or village land gift) movement – created a legal instrument for just and equitable land tenure.

Land would be owned by a non-profit, democratic, membership-based organization; taken forever off the speculative market by holding title in perpetuity; used for homesteading or farming or cottage industry in an ecologically- and socially-responsible manner; and controlled by a tripartite board composed of land users, the surrounding community, and some representation form the broader land trust movement, such that each group of stakeholders had a voice in decisions and no group (including those who lived on or used the land) would have majority control.

The community, in the form of the non-profit group, would own the land and be able to access its increasing equity through loans as well as receive lease fees to cover the cost of taxes, insurance, and administration. The land users would own their homes and any other real improvements that they created, including improvements in the productive value of forest or farm, but they could sell their equity only to another person willing to accept the land-use restrictions determined by the community, sign a lease, and only for what they actually invested plus inflation and minus depreciation.

This model of land stewardship - which was consistent with the ethical positions of the Old Testament, John Locke, Thomas Paine, Thomas Jefferson, and Abraham Lincoln – could have revolutionized land tenure in America if it hadn't been watered down and co-opted by well-meaning groups only interested in affordable home ownership.

Just like the "green" building movement, which is almost exclusively concerned about operating energy to the exclusion of the manifold ecological and cultural elements of shelter, the modern CLT movement has lost sight of the forest for the trees.

So I, who had been part of the CLT movement and knew some of its principled founders, now simply try to do my little bit to create responsible and affordable shelter for people with an authentic need and limited resources. I'm happy to report that the other clients whose super-insulated, passive-solar homes I designed and built continue to enjoy their cozy homes.

Low Profit and Usable Square Footage

Robert,

If you offer to build for well below the market value to help those who cannot afford more expensive homes, I assume you have a waiting list of clients. How do you decide who you will build for? Do you interview them and look at their financial situation?

I assume you take the outside measurements of the home when you measure it and give a SF cost. If I understood your artical, your exterior walls are 12" thick. You should measure to the outside but I try to point out to people that when they look at thick exterior walls, they need to realize the cost of their "useable square footage" goes up.

Interesting article.

Response to Bob Ellenberg

No waiting list. All my work has come by word of mouth, or perhaps more accurately by the Universe putting me in the path of those who needed my services. I work only when work comes to me.

Since I am not a conventional builder (and have no crew), it's only unconventional people who come to me for help. All my house projects have been collaborative with the client, and much of my work has been in the non-profit sector, including volunteer projects with as many as 300 participants.

I rely on gut feeling, or what we used to call intuition, to determine whether a working relationship might be a satisfying one for all parties. I then work with the client to assemble an appropriate crew, which might include the homeowners, and others who are interested in this type of construction. Even mechanical subcontractors, when they're used, are generally those willing to work time and materials and in a collaborative manner. I have built, however, with no subcontractors other than excavators, since I am a master builder with experience in all phases of construction, from foundations to roofing, exterior and interior finishes, insulating, wood and tile flooring, masonry chimneys, custom cabinetry, electrical and plumbing & heating. I do all my own design and engineering as well.

But we need to dispel this absurd notion that there is less "usable square footage" with a thick, super-insulated wall section. A super-comfortable and healthy interior is far more "usable" than one that lacks uniform comfort. And the amount of usable space is far more a function of creative and intelligent design than raw square footage.

While we find it convenient to compare construction costs with the simple metric of $/SF, it's a meaningless ratio, since it's ultimately not the price of the space but rather the value of the space that matters. In our highly dysfunctional culture, we value nothing that doesn't have a price and often neglect to assign monetary value to those things that are most important to quality of life.

A well-designed and carefully crafted small house is often far more valuable as a living space than a poorly-designed and thrown together McMansion, yet the $ per square foot will be higher even if the overall cost is lower - and that is cost to both the owner and the environment.

By your standard of "usable square footage", a client would get a better "value" with a 2x4 house with fiberglass insulation. The absurdity of this should be self-evident.

.

Discouraging ending

I enjoyed all the elements of this story until the end. I'm trying to persuade a prospective client to use a double wall instead of ICF and use pigmented stained siding instead of fibre cement. The saving grace, as you say are the accolades you received and the young couple now enjoying the home. The loss ultimately goes to the original owner.

Flippers

I had a similar happening over 20 years ago when the young couple I had just built for decided to take the money and run. I learned then to charge adequately for my time and expertise on all projects.

Response to Doug McEvers

Same experience - two entirely different responses.

I decided to continue charging what I felt was a reasonable hourly fee with no markup, overhead or profit and Doug decided to charge what I assume is a market rate with all the perks.

Of course it all comes down to what I mean by "reasonable" and what Doug (and others) means by "adequate".

Since I don't feel that "market" labor rates are reasonable - in other words, based on what would make housing affordable to ordinary working people - but rather "what the market will bear", which means the highest possible wage that still allows one to get work.

In my area of the world - the ski resort spine of Vermont - in which a full 40% of the houses are second homes for out-of-state people with too much money and who are contracting most of the new construction, "what the market will bear" is what a wealthy flatlander can afford to pay (which they're thrilled to pay because it's still less than Boston or Hartford or NYC rates). But this means, not only are land values going through the roof because of this out-of-state market pressure, but carpentry labor costs for local working folks are the same as for those who can afford a vacation home. And those two elements together mean that people who are born and raised here cannot afford to live here (and here is the kicker) unless they get on the gravy train and charge exorbitant fees to service the needs of the out-of-state wealthy.

So this becomes one of those "vicious" or self-stoking cycles in which only the wealthy or the greedy can survive. And it's a microcosm of our entire economy.

It's similar to our debt-based economy (something that Thomas Jefferson railed against and probably got Lincoln and Kennedy shot for trying to alter), in which capital is available to entrepreneurs only if they can grow their business fast enough to pay back capital and interest and make a living. This creates a constant pressure for continual growth in a finite world in which the only living thing with an unlimited growth paradigm is cancer. And it means there is constantly more "money" infused into the economy, making money worth less and less (inflation as a structural element of the economy) and making businesses grow even faster to keep up or get ahead of the curve. And it makes ordinary middle class people desire to own a home (or play the stock market) which will inflate in value faster than currency and creates a speculative pressure on human shelter (and every other commodity) which makes it increasingly unaffordable to the masses.

Now we are at the point at which all these economic "bubbles" or speculative expansions are bursting and there are no more bandaids to keep the myth of endless growth together. In other words, a paradigm that had failure built into the foundation of its design has reached the end of its usable life. A shell game, as Bernie Madoff knows all too well, can be shuffled only so long.

So, as nearly impossible as it is within this crumbling economic paradigm, I'm trying to do my small part to live out a different way of being in the world which does not contribute so heavily to collapse, and which seeks to manifest a somewhat different and "steady-state" approach to life, similar to that of the rest of the Web-of-Life. I can't completely live by this different paradigm, as I find I have to increase my rates every few years just to keep food on the table. But it's a start.

I like the idea of a philosophical builder with a green bent who can incorporate more than one idea into design. I've been subsidizing my sales of organic sourdough bread with my labour for thirty-six years now. Why it is that workers that produce tangible products are paid only a fraction of what workers producing intangible products is a puzzle to me. I charge prices that will put some food on the table and give discounts to those that need them if I'm able. I should charge the $300 per hour lawyer $75 for a bread but I don't think that will fly.

I'm planning a house for extended family just north of you in Quebec and wonder if you have any new approach to the `build it super tight and super insulated', then make lots of holes for the expensive and complicated ventilation system.

Nils,

My understanding is that Robert Riversong retired about five years ago. Circumstances may have changed since then. I think he still maintains a blog where you could contact him.

https://riversonghousewright.wordpress.com

Reasonable rates

Robert, I do not overcharge for my work, I just like fair compensation. We are judged by our previous work in this business, both for quality and what it fetches in the market. My customers like my work and my pricing and I have done a bunch of favors over the years for folks with limited means.

Top quality workmanship, priced failrly is the mark of a good businessperson. To cover all of the costs that go with modern building, one cannot give his or her work away and stay ahead of the accounts payable.

structure

Robert, thanks for a great article. There's a lot in here to learn and discuss. I had a question about the structural horizontal loads. I know that you don't use sheathing or diagonal bracing, and in your picture caption you mention the use of 'T' bracing at the studs as they meet the plates. Were there any structural calculations done for this house?. It would seem to me that with those large two-story facades, that they'd pick up some mighty wind loads.

Thanks.

Chris

Response to Doug

I didn't suggest you "overcharged". I assume you're a reasonable and good person.

My point (among others) was that what we think is "fair compensation" is a mostly subjective and arbitrary metric, and it's measured against what the market will bear, which - as I argued - is not a fair basis for comparison, and is a constantly moving (upwards) target.

One of the most successful world-class industrial sectors in the world is in the Basque region of Spain. It is the Mondragon Cooperatives, established in 1956 and now with revenues of 17 billion Euros and employing 85,000 people in 256 companies. From the beginning, they established a maximum:minimum wage ratio of 3:1 because their business model was based on solidarity, worker ownership and control, and equitable and fair compensation. That means their upper managers make 30% less than those in similar regional businesses and their workers earn 13% more.

They base their business model on the "10 Cooperative Principles": Open Admission, Democratic Organisation, the Sovereignty of Labour, Instrumental and Subordinate Nature of Capital, Participatory Management, Payment Solidarity, Inter-cooperation, Social Transformation, Universality and Education.

Every factory floor worker must take a turn at management. This not only puts practical expertise into the manager's offices, but makes administration a responsibility rather than a privilege. And, unlike the US system of interlocking corporate directorates which concentrate power into the hands of the few, the Mondragon cooperatives - which include the fields of finance, industry, retail and education -

have cooperative boards in which representatives of each sector help determine the business plan of the other sectors so that each part serves the whole.

There are many ways to organize an economic enterprise, and we tend to think inside a very narrow box in the US, where maximization of profit has always been the primary, if not only, guiding principle (and is mandated by law for corporate boards).

Response to Chriss

I do all the structural engineering for my designs, but I did not calculate wind loads. I used an IRC approved method of shear bracing for normal (<90 mph max) wind speed zones.

Because the outer framing is gusseted to the interior, load-bearing frame 24" oc with solid, full-dimension 1x4, all windloads are transfered to the inner frame, with the floor and ceiling assemblies acting as shear members. The inner frame has the code-approved Simpson TWB "T-bracing" extending in most cases from plate-to-plate and nailed per manufacturer's specifications.

Because I had some ½" CDX left over from protecting the tinted slab floor, I also created an interior shear wall perpendicular to and near the middle of the north wall for additional stiffness. Additionally, all drywalled interior partitions that are tied to exterior walls serve as shear walls. This is a very stable house.

Further Thoughts on "Fair" Compensation

Doug said: "Top quality workmanship, priced failrly is the mark of a good businessperson."

I would word that differently. Quality workmanship, fairly priced is the mark of a good tradesperson.

And this small difference in semantics represents a world of difference in how we relate to one another economically.

It used to be that when we needed a house (or a wagon, or a barrel or or horses shoed) we would go to a neighbor with that skill and trade him for something he needed, which might be money but could also be eggs or meat or potatoes. Money was little more than a means of exchange by which we could trade for the potatoes from someone else. It was basically a barter economy in which necessary economic trades were made. There was no profit, and overhead was a foreign concept.

There were not even any taxes, since for the first part of the life of our nation, only profits, dividends and interest (unearned income) were taxed. Wages were never taxed because there was no net gain - one merely traded one's time and skills for either potatoes or money. The trade was "fair and square" and every party benefited with no one exploiting the other.

Now, not only have we perverted the concept of basic human shelter into a commodity by which each homeowner hopes to profit (unearned income), but every tradesperson thinks of themselves as a business person. And business, of course, requires factoring in overhead and profit and almost always requires constant growth to keep up with "accounts payable" and remain "competitive".

I have never been a business person. I have developed considerable expertise in a number of trades, by which I hope to give quality work at a fair price and, in so doing, serve my community and my world. The "profit" I receive from my efforts is seeing that I'm leaving the world a little better place. That is priceless.

Appreciation and a thought

Robert Riversong, I’ve been waiting for this explanation. I’d read your links to several bits and pieces elsewhere, but for a consumer this overview puts your approach together in a way that is coherent and understandable. Thanks. I wish I’d known about all of this when I built my post-and-beam barn house in New England 35 years ago.

Now I extend kudos from the sunny Southeast, along with an observation – your customers are very, very fortunate to work with you. And you are exceptionally fortunate as a businessman to be blessed with both skill and passion, and to live where you do, and to find customers willing to commit their life and savings to your production and expertise.

I appreciate the distinction you draw between your practices and values and the ‘ordinary’ concerns of business. I understand, but when your customer moves in, it is equally clear to me that a transaction has taken place. Whatever “currency” was involved, financial and/or environmental, the exchange was value-added and you both have been clearly enriched by the business you've conducted.

Joe W

Thanks Joe, but...

I appreciate your recognition of the value that I both give and receive in my building transactions, but I decline the title of "businessman" (as I thought I had made clear in my previous comment on fair compensation.

From Wikipedia:

"A business (also known as company, enterprise, or firm) is a legally recognized organization designed to provide goods, services, or both to consumers or tertiary business in exchange for money. Businesses are predominant in capitalist economies, in which most businesses are privately owned and typically formed to earn profit that will increase the wealth of its owners."

I have never had a "legally recognized organization" for the purpose of creating profit and increasing personal wealth, nor have my economic transactions been for the purpose of increasing personal wealth - only to make a modest living.

Yes, I engage in economic transactions, or trades. And that is why I refer to myself as a tradesman. In a fair economic transaction, each party receives equal value and no party profits at the expense of the other. There is no net increase in wealth for either party - each receives in equal measure to what each gives.

This is authentic egalitarian trade or economic transaction, which is possible only when we view our clients as equal partners or stakeholders in an enterprise and insist that they "profit" as much as we do. But "profit" in this sense is a much broader non-economic enhancement of life.

"For what will it profit a man if he gains the whole world and forfeits his soul?" - Matthew 16:26

Well built house

Robert, Thank you for providing the pictures, specifications and details for this house.

A few questions

Robert,

Thanks for sharing. This article is a great addition to the information you've provide at the Build-It-Solar website:

http://www.builditsolar.com/Projects/SolarHomes/LarsenTruss/LarsenTruss.htm

A few comments / questions:

1) I love the hayloft access point. It eliminates the complications of having to insulate and airseal a ceiling / attic hatch (which it looks like you used on some previous buildings). For the second floor lighting, how do you keep electrical penetrations out of the ceiling? Or do you also seal these with the Lessco pans?

2) Why asphalt for roofing? Affordability? I would be interested to hear your thoughts on roofing materials. Although recycling is becoming more common, asphalt is typically a "disposable" roofing material. Why asphalt instead of standing seam metal or wooden shakes?

3) On the Build-it-Solar website you mentioned that if a customer wanted to use clapboard siding, you would "sheath with diagonal rough-sawn boards and skip the metal t-bracing." This method would tie the exterior balloon framed walls together, but not the interior structure (which, if I understand correctly, supports the second story floor and roof). It seems like this method would not connect the load paths. Would the diagonal boards minus the let-in bracing provide the shear required for the structure?

Again, thanks for the transparency and information.

Daniel - Good Questions

In this house, there were no ceiling lights on the second floor. We used wall sconces for the stairwell and greatroom and switched receptacles for the bedrooms. The bathroom has a wall-mount vanity light and the fan/light (which is the area lighting) is in a dropped soffit over the tub/shower unit so the ductwork is below the air and thermal barriers (and the duct, like all the other ducting, drops 3' in the wall cavity before turning out to prevent cold air thermo-siphoning). We could have used ceiling lights with Lessco polypans (as we did in the mudroom), but this makes both wiring and air-sealing simpler and creates a nice low-light ambiance which can be augmented by lamps.

The roofing is a compromise, largely for affordability. Quality asphalt shingles (I use the laminated architectural ones) can last 30-40 years, by which time there will almost certainly be lots of opportunity for recycling and many more affordable PV options for replacement. I also like asphalt shingles for their ease of installation, the simplicity of repairing small sections, the ease of modifications or alterations, the simplicity of flashing, and that they hold the snow on the roof. The four things I don't like about standing seam metal are the cost, the difficulty in repair and modification, the challenge in proper flashing, and that it causes avalanches of snow which can rip off vents and gutters, destroy shrubbery, and make snow clearing very difficult (I'm also unsure about the recyclability of metal with baked-on enamel or galvanized coatings). Wooden shakes are also expensive, flammable (all of my homes have woodstoves), and can become a growth medium for moss and algae if shaded or covered with pine needles. However, I just took a class in slate roofing and am excited about the possibility of using recycled slates - which is still not cheap and is labor-intensive but offers a very durable and highly fire-resistant roof.

As for shear resistance, the floor/ceiling load is purely vertical and requires no bracing. The floor/ceiling assembly can help wind brace the exterior walls but this will also happen with my trussed wall system in which the inner and outer framing is tied 24" oc. The roof should be supported by a diagonally-braced wall, and I've designed double-wall systems in which the outer wall is the roof-bearing wall, while the inner wall supports the floor, keeping the band joist on the inside of the thermal envelope. But, even with my trussed wall system, the rafters are tied to the outer chords which could have let-in ledgers to help transfer those loads.

For those of you unfortunate enough to be building in code-enforcement jurisdictions, you'd have to clear any such non-conventional methods with the inspector or hire an engineer to give his stamp of approval. But there are a variety of ways to skin this cat (or house). My latest house design, which is going up in southern VT right now, is a double KD 2x4 wall system with exterior CDX sheathing, the inner wall supporting the second floor and the outer wall supporting the roof trusses (I haven't used roof trusses in decades, but this project seemed to need them). It uses my standard air-tight drywall approach and dense-pack cellulose (of course), but the builder wanted to use Advantech subfloor (which I would avoid - I had spec'ed plywood Sturdifloor), and he insisted on a rainscreen for the siding (which I find unnecessary with a breatheable wall system).

Thanks

Thanks for the responses Robert.

I really like your no-ceiling-penetration-methods.

I laid a Vermont Purple slate roof about six years ago. Many of the things you said about SS metal can also apply to slate (cost, accessibility, snow). But a good quality slate is a purely natural material that will last 100-150+ years if installed well. If you haven't seen Jenkin's "Slate Roof Bible," I highly recommend his book. He's a stickler for using time-approved methods (for instance, he won't lay a slate roof on plywood - he requires solid board lumber). The book also delves into the history of slate roofing and mining across the pond and in other areas of the world.

Yes, code approval for a truss wall was at the heart of my question. I think that the "interior" double-stud wall is more common because it doesn't have to address many additional engineering or code questions. But the balloon framed truss-wall is superior in that it eliminates the thermal bridging through the rim joists (a critical area); it just requires more forethought / structural analysis. It's outside the current paradigm.

Structural Question concerning Double-Stud Walls

Is it a sensible idea to build structurally independent framing for the exterior and interior of a house?

By this I mean having an interior frame which supports floors and ceilings and an exterior frame which supports sheathing, WRB, siding and the roof. They would be linked at the door and window penetrations but not elsewhere. The gap between would be filled with dense-pack cellulose.

Or am I missing something fundamental?

missed something

Both sets of framing would provide their own shear resistance by sheathing, diagonal braces etc.

loading cellulose on ceilings?

Any issues with ceiling insulation R 60+ on drywall ceilings? Nail pops or sagging or deflection in the ceiling joist bays?

Response to Tim

Tim,

Here's one reference: "One drywall manufacturer recommends loads of no more than 1.3 pounds per square foot (6 kilograms per square meter) for 1/2-inch (1.3-centimeter) ceiling drywall with framing spaced 24 inches (61 centimeters) on center." (http://www.doityourself.com/stry/loosefillinsulations).

That sounds too conservative to me. (It would indicate that R-60 cellulose weighs too much for such a ceiling.)

Obviously, 16-inch-on-center framing is better than 24 inches, glued and screwed drywall is better than nailed, and 5/8" drywall is better than 1/2" -- so there are a lot of variables.

cellulose and weight on ceilings.

thanks Martin for the information. I contacted the Cellulose association and they referenced this article

Following proper fastener spacing recommendations, sagging due to unsupported insulation should be

virtually nonexistent in newer homes. With existing homes, the culprits are the condition of the fastening system and condensation. 18 RSI-Augus11990

-- -.'

INSIDE INSULATION

The myth of sagging ceilings

Over the years, the subject Hons-at an R-38 perf orof

ceiling insulation m a n c e level-verweight

has occasionally miculitc, rock wool and

come up especially when cellulose are all on the

the Department of Energy edge or over the limit.

put together the Residen- Vermicuhte or perlite

tial Conservation Service would weigh up to 5 psf of

Program (RCS) m orc more, while rock wool

than a decade ago. and cellulose would be

The ReS Final Rule somewhere in the range of

stated: "(The) provision from 1.5 up to 3 psf. Firegarding

maximum al- berglass comes in at about

lowable loads on attic 1 psfor less.

floors ... is reserved in While many of you Arthur W. Johnson the Final Rule pending A principal in Art Johnson & blow loose-fill insulations

additional comments." Assoctates, Gaithersburg. MD on a daily basis, or did so

However, I find no reference to any later for years, weight per square foot may

provision in the RCS program. Installa- not be so easy to envision.

tion standards speak to clearances To understand what's going on, it's

around recessed light fixtures, inspcc- useful to separate the framing from the

tion for prior moisture damage and nat- gypsum board or plaster interior ceiling

ural ventilation minimums, but nothing finish. The framing system is designed

on weight limits. not to carry, but rather to transmit the

I contacted both USG Building Sys- "dead" loads (snow, wind and stored

terns and the Gypsum Asssociation to attic junk) to the outside top wall plates

try to determine the origin of the weight or those of interior bearing partitions.

per square foot maximums shown in the Framing systems,particulary trusses.

USG Gypsum Construction Handbook. are designed to act and react to loading,

They recommend maximum weights of with some members in compression

1.3 psf for J/2-inch board on 24-inch and others in tension as a cornpensaframing.

and 2.Zpsfwith 16-inchorwith tion. At the framing-to-ceiling finish

jiB-inch board on 24-inch framing for : line, the fasteners will carry the weight

"unsupported insulation." Ifthe insula- . of the ceiling finish.

tion is unsupported (loose fill), they reo- Applying gypsum boards with the

ornrnend no insulation over 3/s-inch long dimension perpendicularto the diboard.

rection of the framing cuts the unsup-

It appears that these maximum in- ported length of'cach board to 48 inches,

sulation weights are somewhat arbitrary as opposed to 96 inches with the long

and have become a "rule-of-thumb" of board dimension parallel; board stiffthe

industry. This likelihood was infor- ness is therefore significantly increased.

many confirmed in conversations at the Following proper fastener spacing recrecent

BOCA Code Hearings. omrnendations, sagging due to unsup-

It seems that the prime concern is one ported insulation should be virtually

of appearance, with an objectionable nonexistent in newer homes.

amount of sagging ofthe ceiling board as With existing homes, the culprits are

the possible weak link. No on I spoke the condition of the fastening system

with in the industry seemed to feel that and condensation.

ceiling board failure was a problem. Next column, we'll examine what

Translating the 2.2 psf limit to com- needs to be done to assure that our prodmanly

available "unsupported" insula- uct doesn't take another bum wrap."

seems like the older i get things just keep getting unclear... tim

This article reads as if it was put through a shredder before posting.

sheathing, second story floor joists

This is a great article.

1) I would love to hear your views on the benefits of metal bracing vs. ply or OSB.

2) How did you frame the second floor joists? If they are 24"oc over the studs, what did you use for joists and subfloor?

compensaion for value added

Robert,

I have read about your homes on several different websites. I wanted to write you here to say that I appreciate your philosophy, and your integrity as you have described your practices in this comments section.

To support myself in our crazy economy, I have been a ski instructor, and a math teacher, the latter for the past nine years. Several years ago, I had the opportunity to buy my first house. I bought 1946 2 bedroom house here in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada.

Of course, this being California in 2004, the house was an absolute wreck, and priced at $247,000. We were overjoyed that we could afford any house, and looked at the needed repairs as an adventure. I picked up a circular saw two days after we bought the house with only junior high wood shop as my training (20 years prior), and began cutting into the rotten sub floor. Right away, I loved the work. Even the somewhat less than aesthetically pleasing tasks of undoing bad remodel work from the 1970's.

Our house was humble at 951 square feet, but unique all the same. When they built it it was a budget house, but even a budget house back then was built on site, one board at a time, without trusses, and designed around the peculiarities of the split level building site. We got settled in the house and focused our attention on the separate single car garage.

The garage was built 2 feet back from a six foot high mortared stone retaining wall that runs the length of the lot, with the house siting 12 feet away from the base of the retaining wall -tight quarters to say the least. The garage itself has a stem wall on the downhill side which is about four feet tall, and is itself a retaining wall holding back the fill that allows one to park in the garage.

When we moved in, the garage stem wall was in the process of failing catastrophically. The was a 16" wide crack in the earth inside the garage, running the length of the parking area. One January day, when my girlfriend was out of town, I got really motivated and trenched out all of the failing dirt behind this foundation with only a shovel (4'x4'x26'). This was the beginning of a massive project where I built a temporary post and beam frame on a set of 4x4 screw jacks and raised the entire downhill side of the building about 2". I built a set of braces akin to something that a shipwright might build to keep the tilted foundation from falling downhill on the house, and jack-hammered the foundation into pieces. I removed all of the debris, framed up forms for a 10" thick stem wall with little buttresses, and formed the new stem wall under the garage framing. I worked slowly and taught myself each task, reading about procedures and talking to friends. The most difficult part was the sequencing, as there work area was extremely limited and all of the area below the garage was filled with extensive landscaping. In the foundation came out nicely, albeit somewhat missile-proof as I consistently erred on the side of building stronger than what was required.

On the last day, where I was re-framing the barn doors on the front of the building, the city inspectors showed up. To this point I had $2700 into the project. My neighbor had reported my repair efforts (despite my precaution of using power tools only from 8am to 5pn, and constantly sweeping and hosing off the site).

To make a long story short, The final project cost me $15,000 in materials and engineering. The inspectors said that my garage was too close to the retaining wall below it, and the engineers gave the stone retaining wall a big zero in their calculations (despite the fact that it is still standing undamaged after 60 years). I offed to tear down the garage, but the inspectors explained that I would be responsible for engineering a retaining wall to hold up the street above my garage! the solution involved boring four 18" diameter caissons to a depth of 23 feet and forming four accompanying grade beams each with a cubic yard "deadman" tieback anchor. I completed all of this work myself (except the limited access drill rig operation), while maintaining my civility towards the inspectors and engineers - surely a herculean task.

In the end we deeded the house back to the bank, as our loan adjusted upwards after 5 years, and our house was $140,000 upside down. I am telling this story not for sympathy, but as an amazing confirmation of just how bizarre our system is. I worked on that house nearly every weekend for four years, and today the stands far better than when we bought it. All of my repairs were practical, necessary repairs after 60+ years, none were overpriced luxury items. For all of my work I will be making payments for the next 10 years to pay my family back for the assistance we received with the down payment. Surely my work was worth something? The garage foundation alone would support a three story building for the next 500 years... The buyer of our house was a landlord looking for rental income. Most of the hand-propagated landscaping is now dead (and still standing as an eyesore). Go figure. I am proud of the work I did, honored by the fact that I had the opportunity to use the building materials to show my best work at the time. I now take on small construction jobs for our friends. I charge based upon my knowledge of the task at hand. If I have to teach myself something and work slowly, I charge an apprentices wage. I know how to do something well, I charge more, but still very little compared to the going wage. I love the work, and only with that more people had the vision to ask for more artistically interesting solutions to their building needs. Often time good design doesn't cost that much more, it just looks better, lasts longer, and is more gratifying to build.

Sincerely,

Brian Austin

What would you do differently in warmer zones? (3A and warmer)

Robert,

I've been perusing this site for a couple of months and always enjoy reading your passionate comments as they add an additional perspective (Dana is another).

Q: Do you think this building system would perform in warm & humid climates (Zone 3A and below)?

Q: Would the required wall thickness be reduced to the point that the system would perform no better/worse than say conventional framing with mineral wool batts, mineral wool exterior sheathing and a rain screen?

I imagine using green lumber would be a challenge in the southeastern US with the year-round high relative humidity.

TIA

Response to Chris M

Chris,

The Building Science Corporation (BSC) has developed R-value recommendations for various building components (floors, walls, ceilings, and roofs) in a variety of climate zones. Of course, higher R-values are recommended in cold climates than warm climates.

Here is a link to the table that includes these BSC recommendations:

Building Science Corporation R-value recommendations

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in