In the 1970s and 1980s, the practice of installing polyethylene on the interior side of wood-framed walls became common in much of the U.S. These days, however, installing interior poly is nowhere near as common as it used to be; the practice has all but disappeared in the U.S. outside of Minnesota and Alaska.

In Canada, however, the use of interior polyethylene is alive and well.

Why did American builders abandon interior polyethylene? There were two main reasons:

- In the late 1990s, there were several well-publicized clusters of building failures — notably, wet-wall problems in North Carolina and Ohio — in which polyethylene was implicated as a contributing factor.

- Several well-known building scientists, including Joseph Lstiburek, warned builders that the use of interior polyethylene was risky in homes with air conditioning.

The roller-coaster history of interior polyethylene leaves many builders, especially Canadian builders, with lingering questions. Here at GBA, we occasionally get questions from Canadians who ask, “Should I still be using interior polyethylene? Everyone up here uses it, and building inspectors want to see it.”

These are good questions. It’s time for a fresh look at the issue of interior polyethylene.

A brief look in the rear-view mirror

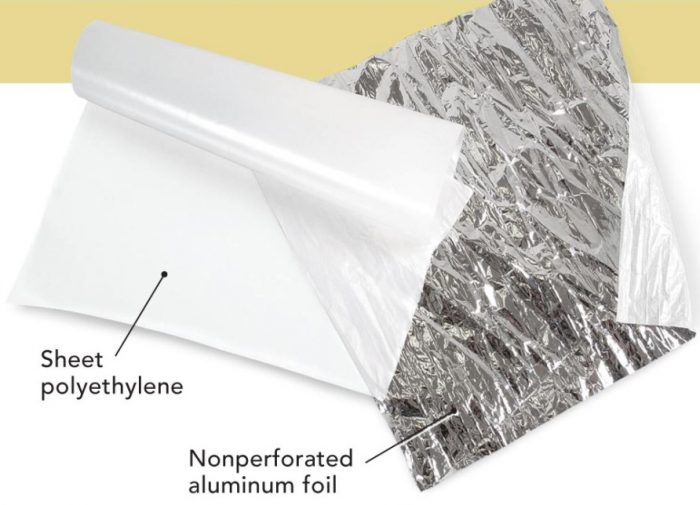

Why did cold-climate builders begin installing interior polyethylene in the 1970s? Back then, the standard answer was, “Polyethylene is a vapor barrier. Walls need interior vapor barriers to prevent the outward flow of moisture during the winter.”

In fact, carefully installed interior polyethylene often improved the performance of cold-climate walls. However, the main reason that interior polyethylene helped wall performance was because the polyethylene was installed as an air barrier. Even back in the 1970s and 1980s, conscientious Canadian builders were installing polyethylene with taped seams or seams sealed with Tremco acoustical sealant. Whether the builders knew what they were…

Weekly Newsletter

Get building science and energy efficiency advice, plus special offers, in your inbox.

This article is only available to GBA Prime Members

Sign up for a free trial and get instant access to this article as well as GBA’s complete library of premium articles and construction details.

Start Free TrialAlready a member? Log in

32 Comments

Thank you, Martin. I live in a house built in 1979 that has interior polyethylene (between the drywall and the stud wall). Being in northern Indiana, we don't find much use for air conditioning, but that's been changing as the weather gets warmer (especially the nights!). I wonder where the threshold is before A/C use starts causing problems.

Your last paragraph gives me some comfort - I figure the house has made it this far, so it can't be too bad. Also, most of my neighbors use far more A/C than I do in houses built by the same people at the same time, and their houses are still standing.

I still fantasize about someday ripping all that poly out, though, on my way to retrofitted high-performance wall assemblies. It's good to have dreams.

We were building in 2009, after the open cell SF was sprayed into 2 X 6 walls then trimmed flush, the building official said we needed a vapor barrier. He would not sign off on the insulation until interior poly was put up over all walls & ceiling. To bad we didn't know there were other options.

We are in north west Rhode Island, zone 5. Heat and cool w/GSHP and enjoy a/c in the summer. The house had very high RH for a long time before starting to actively dehumidify. 2009 was a wet year and poly was put under 2" XPS in basement slab.

I PMed Dana Dorsett in 2011, he said that with the plywood sheathing and cedar shake siding we should be fine, the walls would dry to the exterior.

The above comment from Dana in the above post gives me a little comfort also, I think...We built our house on Martha's Vineyard in 1982 using what at the time was considered a state-of-the-art wall system. 2x6 studs with R19 insulation, a layer of foil faced polyiso against the the interior studs with taped joints, 1x3 furring, and sheetrock. The exterior was plywood sheathing, asphalt felt, and cedar shingles.

We didn't have A/C until about 10 years ago. With the warmer summers, it's been engaged a good amount of the time in July and August. We've seen no problems. I'm thinking that the 3/4" polyiso is reducing any potential condensation against the vapor barrier, and whatever there may me has a potential to dry to the outside.

Hugh,

While foil-faced polyiso is a vapor barrier, it doesn't behave anything like polyethylene -- because the polyiso has R-value. The first surface encountered by any solar-driven moisture (in your case, the exterior side of the polyiso) will be relatively warm, not cool (as would be the case with polyethylene) -- so you won't have condensation problems.

You need a cool surface for condensation to occur.

I think #3 under "Analyze Your Goals" will be the most relevant for most Canadian builders. Most inspectors simply want to see some sort of plastic go up. That being said, in my limited experience, most are fine with MemBrain. A potential unnecessary cost, but choose your battles.

"Most of the problems occurred in EIFS-clad homes — in part because EIFS-clad walls dry very, very, slowly to the exterior. The walls that dried the most slowly of all not only had EIFS on the exterior, they also had polyethylene on the interior. These walls were prevented from drying out in either direction. The EIFS cladding prevented outward drying, and the polyethylene prevented inward drying."

I asked Joe Lstiburek about this at the 2004 Better Building Better Business Conference in Green Bay if front of 500 people. "Would the EIFS homes have failed without the polyethylene warm side vapor barrier" he said yes, just not as fast. The EIFS problem was one of improper moisture proof layers between the exterior sheathing and the EIFS.

To be clear, the problem wasn't improper moisture proof layers. There were NO moisture proof layers behind the skin. The first generation of barrier EIFS was intended to provide 100% moisture barrier at the exterior skin. Even in perfect conditions, this can only be achieved through aggressive attention to details at all edges and penetrations. We can't build boats that are 100% waterproof in factory conditions. It was magical thinking that allowed the EIFS manufacturers to believe that it could be done by marginally skilled workers in field conditions.

Response to Doug McEvers and Peter Engle,

Doug's explanation is consistent with what I wrote, although I agree with Peter that Doug's description of the problems with the EIFS is phrased awkwardly.

The polyethylene was the not cause of the problems in North Carolina, although many building scientists concluded that the polyethylene was a contributing factor.

The type of EIFS installed on the North Carolina homes that failed is now known as "barrier EIFS." The flawed idea behind this cladding was that rigid foam and synthetic stucco could be installed in such a way that 100% of the wind-driven rain would be excluded from the walls. They can't. The theory was wrong. (All claddings share this problem -- they aren't waterproof.)

Since the North Carolina disaster, EIFS manufacturers have developed new systems called "water-managed EIFS" -- basically, systems that include a dimple mat or plastic mesh that allow for drainage of water that gets past the synthetic stucco. Water-managed EIFS performs much better than barrier EIFS.

Any poly sheeting is not recommended on the interior side of the wall with either kind of EIFS, for the reasons you describe in the article above.

Peter,

Right.

EIFS walls have a continuous layer of exterior rigid foam, so they fall into a category of wall that I discuss in my article, "Calculating the Minimum Thickness of Rigid Foam Sheathing."

In that article, I wrote:

"There are two important points to remember about foam-sheathed walls:

• The rigid foam must be thick enough to prevent moisture accumulation (“condensation”) in your sheathing or framing; and

• This type of wall must be able to dry inward, so it’s important to avoid low-permeance layers like polyethylene, vinyl wallpaper, or closed-cell spray foam on the interior."

Martin; I may have inadvertently merged the 1990's EIFS problem with the conventional stucco problem. The conventional stucco/wall failure had much to do with solar vapor drive through the wall sheathing and into the wall cavity. It was this question I posed to Dr. Joe when he said the wall failure would have happened with or without polyethylene.

Martin, based on rule #3, what are your feelings regarding the following: Next year I am building a house in Kenora area of NW Ontario, CZ 7. I planned on using a layer of 1/2” plywood on the exterior side of the 2x4 inner wall as an air and vapour control barrier thereby reducing the risk of wetting the exterior layer of plywood sheathing. I also plan to insulate with Roxul batts and of course, no exterior foam. The plywood layer is considerably more expensive and probably requires as much, if not more labor than a properly and carefully installed 6 mil poly layer behind the drywall (the old Canadian standard). After reading your post, I am wondering whether or not the use of the poly would be acceptable in this situation, and if not poly, would MemBrain work as opposed to the plywood layer. I still lean to the plywood layer for the robustness etc., but wonder whether it may be overkill in our climate.....an unnecessary expense, especially considering the cost of plywood nowadays. Comments?

John,

Either polyethylene or plywood will work. If you expect this layer to be an air barrier, plywood is obviously the better choice. (It's hard to get polyethylene to perform as an air barrier, because polyethylene is easily damaged on the job site.) Only you can determine whether you can afford to install plywood as an air barrier.

If you are also planning to install OSB or plywood as your exterior sheathing, you might consider establishing your primary air barrier at the exterior sheathing rather than where you're talking about putting the poly.

Regarding Rule #4 - what about interior dimple mat for drainage (when even after exterior measures are taken you still get some water inside)? It's a vapor barrier, even though not sold as such, isn't it?

Cramer,

The usual material to install at this location as a vapor retarder is a continuous layer of rigid foam. Dimple mat is rarely required -- but if your basement has a water-entry problem, you might want dimple mat and an interior French drain. For more information, see "Using a Dimple Mat to Keep a Basement Wall Dry."

Thanks Martin - but what's the issue you're trying to avoid by saying (in Rule 4) to never put a VB between the concrete and the stud wall? Adding dimple mat for drainage to a French drain would break that rule, no?

Cramer,

I didn't write "never put a vapor barrier between the concrete and the stud wall." I wrote, "You don’t want polyethylene between the concrete and a stud wall."

Foil-faced polyisocyanurate is a vapor barrier, and it's fine in this location. In a basement with a water-entry problem, you might want a dimple mat in this location, and the dimple mat (as you point out) is a vapor barrier.

You just don't want polyethylene here. The worst example would be a concrete wall with polyethylene, then studs, then kraft-faced fiberglass batts, and then drywall. If the basement is damp, you can come back two years later, open it up, and find a moldy mess.

Martin, I read your comment and then I read my original comment and I wonder if I did not make clear that this is going to be a 2x4 double stud wall with 3 1/2” space between the inner and outer wall.

John,

Just to be clear: Are you moving the exterior sheathing to the outside of the interior wall, and using something else on the outside wall, or are you proposing two layers of sheathing?

Malcom,

No, I’m not moving the exterior sheathing to the interior. I am looking at a putting a second layer of 1/2” plywood sheathing like the stack up in Joe Lstiburek’s ideal double stud wall. Martin’s comments made me wonder if the plywood layer on the exterior of the inner wall is necessary in CZ7 . The sheathing in the middle of the wall stack up, as you know is there to mitigate moisture accumulation on the cold exterior sheathing. Of course, this second layer of sheathing is an expense and if It can be substituted with a layer of 6 mil poly between the drywall and inner stud wall, great. If I want to use a double stud wall in my build in CZ 7 with Roxul batt insulation and exterior plywood, is the poly on the interior a safe option?

John,

The plywood has several advantages over the polyethylene. Plywood is a smart vapor retarder with variable permeance, so it allows for some inward drying if it ever gets damp. It is also stiffer, more durable, and less likely to be punctured than polyethylene. So it's the better choice. This is a budget decision, not a building science question.

If you downgrade to polyethylene to save money, you should (a) strive to repair any holes in the poly, and (b) carefully tape the seams of your exterior sheathing to improve the airtightness of your wall assembly.

John,

I asked because both possibilities have been used successfully. Lucas Durand eliminated the outside sheathing in his build: http://ourhouseuponmoosehill.blogspot.com/p/details.html

and Stephen Sheehy substituted a membrane for the plywood on the outside of the inner wall: https://www.greenbuildingadvisor.com/article/framed-walls-and-air-barrier-membranes-for-a-pretty-good-house.

If you decide to use a membrane or poly rather than plywood, locating it on the outside of the inner wall makes it less prone to damage, but also harder to install.

Other considerations about poly aside, I don't share Martin's worries about successfully detailing it as an effective air-barrier (The tightest house ever tested used p0ly as its air barrier).

I don't think there is any evidence that using poly as an air/vapour barrier in Northern Ontario causes problems. However, you wall will be a lot more resilient if you include a rain-screen under your cladding.

Martin,

Thanks for your responses. I agree on the advantages to the plywood vs. the poly. I would contend however that this is as much a building science question as well as budgetary in so far as: if poly (at some properly detailed installation level) can be effectively used as the main air barrier in cold climates on a double stud wall, then it becomes a viable option. I think that, under the right circumstances, the poly is not necessarily a downgrade.

We are owner builders and have total control over all of the detailing work, so I am confident that we can seal the poly layer as well as anybody could. One of the issues with the intermediate plywood layer is the difficulty of assembly of the 2 walls and being able to properly seal that layer. I have not seen a detailed "how to" on the process of how to install that layer. It seems to me that most of the info/articles I have seen on GBA on this "intermediate layer" topic are from people/builders who are trying to avoid it by coming up with an alternate solution because it is such a difficult detail....I am open to any suggestions however and not totally decided on any one design, except that I know it will be a properly sealed double stud wall with plywood sheathing and rockwool insulation.

Malcom,

Thanks for your response and thanks for the links on alternative designs. I will read through them.

You are correct that putting the poly on the outside of the inner wall is harder to install. I'm not afraid of a challenge, so I haven't ruled anything out at this point. We are starting work with our design person later this week, so these decisions have to be made soon. I also concur with your opinion about being able to successfully detail the poly layer and the lack of issues with it in cold climates. Details are important if you want to use poly as your air and vapor barrier. And I do think the rain screen is important in any assembly especially so when there is no drying to the interior. I would be interested to hear from any GBA subscribers how they successfully sealed that intermediate layer and the issues they had, and how they overcame them.

John,

There are so many possible viable iterations for double-stud walls it makes my head spin.

A lot depends on which wall will be load-bearing.

If it is the inner one, it may make sense to frame, sheath and air-seal those walls, then build the outer ones after. The floor system can be kept flush with the inner walls and if there is a second story the subfloor can be extended out to the outer-wall to tie things together.

If it is the outer, it may make sense to build the inner wall in parts, as Stephen Sheehy did, air-sealing each section as they are assembled.

Although locating the poly at the interior precludes any inward drying, and makes it more vulnerable to damage than if it was located further in, it does mean make it accessible during construction, allowing inspection and corrective steps to do further sealing. In Canada it is also something familiar to both building inspectors and the other trades too. Something not to be under-estimated as a virtue.

John,

You're right that if you are conscientious, you can install polyethylene as an air barrier. But it won't perform the same as a "smart" vapor retarder like plywood, because the plywood allows for vapor diffusion when it gets damp.

I'm not qualified to determine whether the difference matters in your climate -- there are lots of variables, and you'd need something like WUFI to say for sure. (And using WUFI has its own set of problems.) My guess is that using poly in your climate zone would be OK -- but it's just a guess.

Malcom,

I indeed have thought about the various ways to accomplish this and Stephen's method is one way for sure. Our build is a single story and will have a crawI space that I want to be a preserved wood foundation all on steel pipe piles to bedrock or helical piles. I lean toward the outer wall being my load bearing wall like he did. I think that building the interior wall in sections and air sealing as you assemble is also doable, although tricky as you can't reach the seams from behind to seal each section to the next. I think acoustical sealant would work if applied properly. In fact I would consider acoustical sealant at each plywood to framing face to air seal if using plywood on that inner layer. However, with the plywood air barrier layer on the outer side of the inner wall, how would you tie that to your ceiling air barrier? Would you seal the ceiling air barrier to the top plate of the inner wall? Poly or MemBrain on the other hand, if used on the outer side of that interior wall could be lapped over the top of the wall and tied in with the ceiling air/vapor barrier, but I feel that those 2 materials would be more difficult to air seal the wall sections together as they are installed...maybe not. Lots of options....like you say.

"Unless you’re building in Canada or Alaska, don’t install interior polyethylene on walls..."

Hi, Alaskan here. As far as I know, everybody installs interior polyethylene in new residential construction. Is interior polyethylene actually still the best option in our climate, or would a smart vapor retarder like MemBrain work better?

Note: I'm in Anchorage. The weather here is cold by average US standards (Climate Zone 8), but actually pretty mild for Alaska. https://weatherspark.com/y/252/Average-Weather-in-Anchorage-Alaska-United-States-Year-Round

Paxson,

Q. "Is interior polyethylene actually still the best option in our climate, or would a smart vapor retarder like MemBrain work better?"

A. Interior polyethylene is still probably the best option in your climate, because it costs less than MemBrain. But MemBrain would work, too.

Martin,

I am trying to square this timely article (it is still 2019, though barely) and "Rethinking the Rules on Minimum Foam Thickness", November 3, 2017, with a proposed wall detail consisting of cement board cladding, 3/4-in. furring strip/rain screen, 1.5-in. XPS, liquid applied permeable air barrier, 5/8" Exterior GWB (or 1/2-in. plywood), 2x6 with 5.5" min. wool batt, 6 mil poly., 5/8-int. GWB. This is for a 3-story multifamily (35,000 sq. ft. GFA). Climate Zone 5, marine influences so we will use heat pump driven AC from mid May to late September.

A WUFI analysis confirms unacceptable moisture without the poly, and acceptable performance with the 0.1 perm vapor "retarder".

Of course a variable vapor retarder was not modeled, and I don't think WUFI incorporates fugitive water. I am worried that our walls will not dry when they get wet.

If I had my druthers, my nascent understanding of these things has me wanting rigid wool on the outside with wool batts. The story I tell myself is I'll get noise absorption, a less combustible wall and a wall that dries in and out with only latex paint as a Class 3 vapor retarder.

Eddy,

I don't recommend that residential designers use WUFI. To learn why, read this article: "WUFI Is Driving Me Crazy."

Even if the interior of your building is air conditioned during the summer, the use of interior polyethylene is unlikely to cause problems. The main reasons you don't have to worry is that you'll have a rainscreen gap and a continuous layer of exterior rigid foam. These two features eliminate any worries about inward solar vapor drive. So you can relax.

Nor is there any reason to anticipate moisture problems from outward diffusion during the winter -- regardless of what WUFI is telling you. Your R-7.5 rigid foam will keep your sheathing warm all winter long -- so you won't have any cold surfaces in your assembly where moisture can accumulate. So don't worry.

If I were you, I would use MemBrain on the interior -- not polyethylene. But if you end up using polyethylene, your wall won't fail.

As always, you have to pay attention to airtightness to avoid problems.

“[Deleted]”

>"...proposed wall detail consisting of cement board cladding, 3/4-in. furring strip/rain screen, 1.5-in. XPS, liquid applied permeable air barrier, 5/8" Exterior GWB (or 1/2-in. plywood), 2x6 with 5.5" min. wool batt, 6 mil poly., 5/8-int. GWB. This is for a 3-story multifamily (35,000 sq. ft. GFA). Climate Zone 5, marine influences so we will use heat pump driven AC from mid May to late September."

While the labeled R-value of 1.5" XPS meets the IRC's prescriptive R7.5 for 2x6 framed walls in zone 5A, it's failing in a couple of ways:

The presumptive cavity fill for 2x6 walls in the IRC is R20, whereas typical rock wool sold in the US is R23, 15% higher.

The WARRANTEED R-value of 1.5" XPS is only R6.75, 10% less than the IRC prescriptive. The actual performance of 1.5" XPS is really even less than that over the lifecycle of a house, dropping asymptotically toward R6.3 over several decades, which the same as 1.5" EPS of similar density. The higher early-life performance of XPS is due to it's climate damaging HFC blowing agents, a mix of HFCs comprising primarily of HFC134a (automotive AC refrigerant), with a 100 year global warming potential of about 1400x CO2. As the HFCs slowly diffuse out, performance drops.

The vapor retardency of 1.5" XPS is also less than 1 perm (lower than the permeance of even modestly damp plywood), limiting the drying capacity of the sheathing into the rainscreen gap.

If 2" of Type-II EPS (R8.4) the ratio of foam-R/total-R [ R8.4/(R8.4 + R23)= 26.8% ] is pretty close to the IRC's prescriptive [ R7.5/(R7.5 + R20) = R27.3 ], and the vapor permeance of the foam is between 1-1.5 perms, a major improvement in drying rate compared to 1.5" XPS. And the R-value of EPS is stable over time, blown with a lower impact hydrocarbon blowing agent, variants of pentane, at about 7x CO2 @ 100 years, most of which escapes the foam and is recaptured while still at the factory, not vented into the atmosphere.

With or without the 6 mil polyethylene , the 2" Type-II EPS wall is a more resilient assembly than with 1.5" XPS. And with 5 perm paint (typical interior latex primer + 2 coats) on air tight drywall it will probably fly just fine in your WUFI sim (and better yet, in the real world) without the 6 mil poly.

But as Martin suggests, 2-mil nylon (Certainteed MemBrain) has a variable permeance, and will be less than 1 perm whenever the sheathing temperature drops below 40F, which is the most critical inflection point for moisture accumulation in the sheathing at typical residential indoor humidity levels, and would be cheap insurance. There are other, more vapor-tight variable permeance broadsheet vapor retarders out there that would also work, but with any amount of exterior-R the much cheaper 2-mil nylon is more than adequate.

XPS really has no place in a "green building" discussion, being perhaps the least-green insulating material in common use today:

https://materialspalette.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/CSMP-Insulation_090919-01.png

Log in or become a member to post a comment.

Sign up Log in