Image Credit: South Mountain Company

Image Credit: South Mountain Company The South Mountain Company recently installed a large photovoltaic array on the roof of the company's garage.

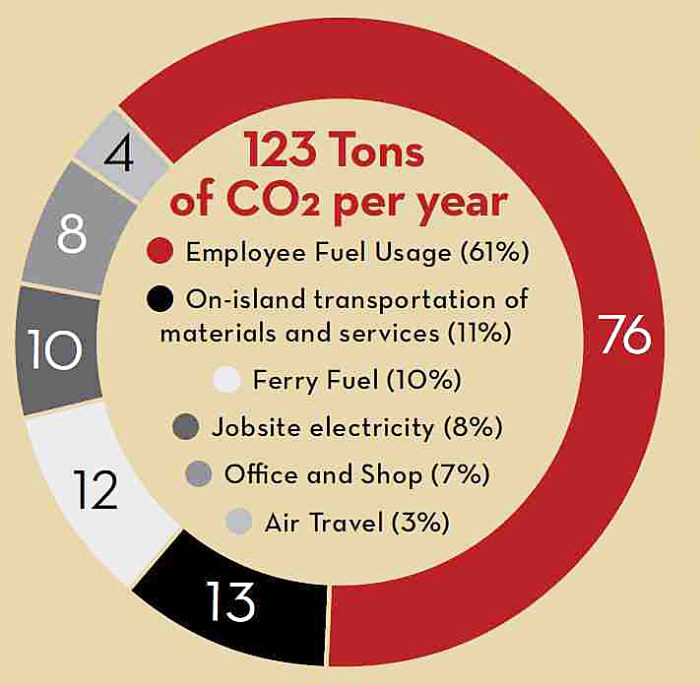

Image Credit: South Mountain Company This poster summarizes the information we learned from our Phase One assessment of our company's carbon footprint.

Image Credit: South Mountain Company

South Mountain Company is a 39-year-old employee-owned company offering integrated architecture, engineering, building, and renewable energy services. We like to measure how we’re doing in as many ways as possible. Like other businesses, we have a collection of metrics for financial tracking: profit and loss, budget projections and actuals, job costing of each project, value of our several funds (pension, equity, and reserves), and more.

We also measure social factors: employee education costs, compensation ratio (top to bottom), length of employee tenure, average employee age, charitable contributions, and community service.

We consistently track (measure) our work backlog to help us plan for our immediate future.

We try to predict our longer-term future, too — through strategic planning, creating five year plans, projecting organizational charts, and making succession plans.

In design and project planning, we do extensive measuring (space planning, engineering) to ensure good building performance, structure, and utility. On our completed projects, we monitor energy use and other factors (like relative humidity) to help us learn what works and what doesn’t.

And, of course, building itself is a process of constant measurement.

This desire — to measure whatever we can as a means of understanding who we are and what we do — inspired us recently to attempt to measure our company carbon footprint. Despite our efforts to build durable high-performance buildings with low environmental impacts, we recognize that all of our buildings have significant impacts, as do our operations as a company.

There are no existing templates for these calculations

We asked ourselves this question: “While we are working so hard to make zero-energy buildings, how are we doing with energy and waste in our company operations?” The answer, despite our consistent anecdotal efforts, is that we had no real idea, so we set out to find out — to learn where our impacts are greatest, and where the opportunities exist to reduce those impacts. By gathering baseline data and measuring impacts, we would create a means to track our progress.

When we first imagined this project, we assumed we would find models and templates. Surprisingly, we were unable to find small companies that are currently measuring their company carbon footprint. (We still think they must be out there; we just haven’t found them yet). So we developed a methodology, gathered the data, and produced the first phase of our carbon footprint assessment. Our director of engineering, Marc Rosenbaum, was largely responsible for the methodology. My daughter Sophie, who works with us part-time while she is working on an MBA in Managing for Sustainability, collected the data from various places and was the primary author of the report.

We have now completed the first phase of this project. Here’s a snapshot that shows that by far the largest source of energy use in our company at present is employees getting to and from work and driving around (hopefully not aimlessly) doing errands during the day! (See Image #1, above.)

Implementing new carbon-reduction measures

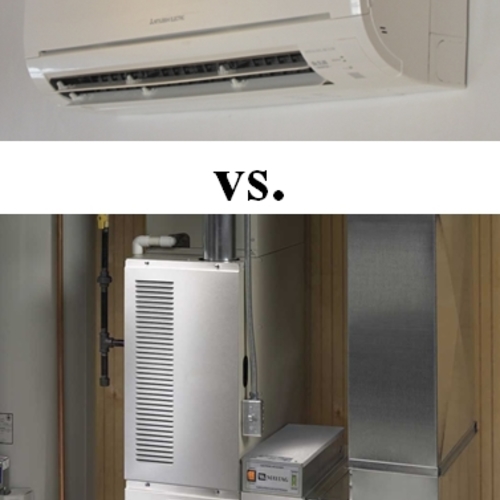

We have just completed a project to make our offices, shop, and storage facilities net energy producers. We added a large solar array and replaced our oil heating system with air-source heat pumps. (See Image #2, below). But since we enrolled in the Massachusetts Solar Renewable Energy Certificate program, which enables us to sell the renewable attribute of the solar-generated electricity, we can’t count it against the electricity we use; that would be counting it twice in carbon footprint terms.

Now we will prioritize reducing our use of transportation energy. We are considering a number of measures which, if implemented, may help with that:

- Operational changes that save trips by our construction crews when in the field;

- Increasing our company’s employee transportation incentive to encourage greater use of public transportation and bicycles;

- Carefully evaluating the benefits and costs of off-island travel, driving, flying, taking the bus, or skipping the trip altogether;

- Ensuring that PV systems are installed and operational as early as possible on projects to maximize offsets of jobsite energy use;

- Examining the possibility of portable jobsite heat pumps for construction heat;

- Lowering our corporate fleet footprint by incentivizing more fuel-efficient vehicles throughout the company;

- Acquiring a company electric vehicle for office errands and short trips during the workday.

We’re particularly jazzed about the electric vehicle, as we have been working to make our facility more resilient in case of an event that leaves us without power for an extended time. The battery pack in an electric vehicle represents energy storage that can supply our facility with power during an electricity outage. If we plan to use our PV array for backup power, it’s likely that we’ll need more storage than one vehicle battery pack provides.

Looking at building materials

We are also ready to begin the second phase of our assessment, which is the complicated part. The materials that we use in our projects are a big part of our carbon impact. In the first phase of our assessment, we only measured the transportation of building materials from Woods Hole (the other side of the water from Martha’s Vineyard, our home territory) to their destination, and the waste these materials generated. But that leaves out, of course, a big part of the story: the materials’ environmental impact from origin to Woods Hole.

For simplicity’s sake, we decided for Phase One that this is part of our clients’ carbon footprint, not ours — a convenient deflection. A procrastination, in fact (like washing all the dishes and leaving the baking pans and skillets in the sink to soak) — but one that was necessary to allow the analysis to be phased.

Ultimately, however, we understand that these materials are, indeed, a part of our impact. More important than who is assigned the impact is the fact that we are the ones who can assess and change our practices, so the ball’s in our court.

The second phase, which we are beginning now, is to dig deeply into a Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) of the materials we purchase for our projects, from the extraction phase through processing, manufacturing, and distribution (along with the current local transportation and waste disposal that we are already tracking). This new part of the endeavor requires extensive research and new learning.

It also means we must consider and interact with our supply chain in new ways — to try to create alignments, in both values and practices, with our suppliers. This is bound to be a long haul.

The beginning of a long journey

In summary, for 20 years or more we have had the goal of reducing carbon emissions, but it has been an abstract goal to which we have only given episodic attention. It may take another 20 years to reach our zero-energy and zero-waste goals, and we are only beginning to learn how to do that. But this first phase of our Carbon Footprint Project has served its intended purposes. We identified the areas in which we are already doing well, found the areas that are most ripe for improvement, and specified the aspects which need further inquiry.

There’s always something new that needs to be measured. Numbers tell stories. Stories teach. This metric feels like one that will be teaching us a lot — for a very long time. While there will be no end to this project, we are no longer at the beginning. It’s part of a path to a restorative future.

The full first phase report is available on the SMC website. We are interested in feedback about ways to improve it. We are also interested in knowing about other companies doing this work. If you have comments or information you’d like to share write to me at jabrams [at] southmountain [dot] com.

John Abrams is founder and CEO of South Mountain Company, located on Martha’s Vineyard in Massachusetts. South Mountain is a 39-year-old worker-owned company committed to triple-bottom-line business practices. John’s book, Companies We Keep: Employee Ownership and the Business of Community and Place, was published in 2008. John’s blog is called The Company We Keep.

Weekly Newsletter

Get building science and energy efficiency advice, plus special offers, in your inbox.

0 Comments

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in