Image Credit: Environment International

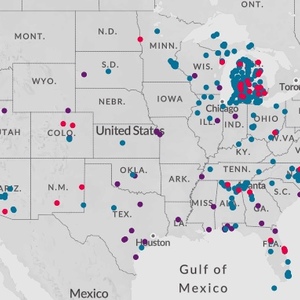

Researchers studying a low-income housing development in Boston have discovered that green certification is no guarantee that a home will be free of chemical contaminants.

Their study measured chemical pollutants in 30 apartments and townhouses that had been renovated and certified under the Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) program. It found contaminants (both in the air and on interior surfaces) that could be linked to building materials or to residents who moved into the units. Some of the chemicals have been linked to cancer and other serious health problems.

The study was published in the journal Environment International.

The housing got a variety of upgrades in the 2013 renovation, including high-efficiency windows, additional insulation, low-energy lighting, new flooring and cabinets, and low-VOC paints. Despite

LEED certification, pre-occupancy sampling found several flame retardants, plastics chemicals, and volatile organic compounds in both air sampling and in surface wipes. Some of them, such as toluene and ethylbenzene, are listed in California as a developmental toxicant or as a carcinogen.

In all, researchers targeted nearly 100 VOCs and semivolatile organic compounds (SVOCs), including phthalates (used in plastics), flame retardants, fragrance chemicals, pesticides, chlorinated solvents, and formaldehyde. Among 58 detected chemicals, the report said, 25 were primarily related to occupants, not the building.

“All homes had indoor air concentrations that exceeded the available risk-based screening levels for at least one chemical,” the authors said.

Lead author Dr. Robin Dodson, a research scientist at the Silent Spring Institute, said in a call the study underscores the widespread presence of chemical contaminants, including some that were phased out years ago.

“While these homes did achieve a green certification, we’re still finding chemicals that we’re concerned about,” she said. “To put this in context, we find these chemicals in every home, no matter what the type — public housing, single-family homes. These are ubiquitous chemicals that we’re finding. It’s true that green buildings have chemicals of concern, but the headline could just as easily say, ‘All homes emit chemicals of health concern.’ “

Low-income housing is a particular worry

Researchers were especially interested in housing for low-income families where there is a “disproportionate exposure to pollutants” from traffic and industry, and where smaller house sizes and occupant behaviors like smoking mean a greater number of indoor contaminants.

The 30 units included two- and three-bedroom apartments ranging from 700 to 850 square feet, as well as three four-bedroom townhouses of about 1,200 square feet.

“Residential design practices aimed at reducing environmental impacts — ‘green’ building — present one opportunity to significantly change chemical levels in homes,” the authors said. Green design has become more common in recent years, and several studies have shown improvements in air quality in newly constructed or renovated green housing, including fewer particulates, black carbon, nitrogen dioxide, and allergens.

But tightening the building envelope to lower energy use also has the potential to increase exposure to chemicals inside the building. Notably, none of the renovated housing units in the Boston study have any mechanical ventilation, a feature considered essential by most designers of well-insulated, high-performance buildings. Dodson said that the Boston renovations were partial, not full gut rehabs, and upgraded ventilation wasn’t included.

Chemicals that residents bring with them

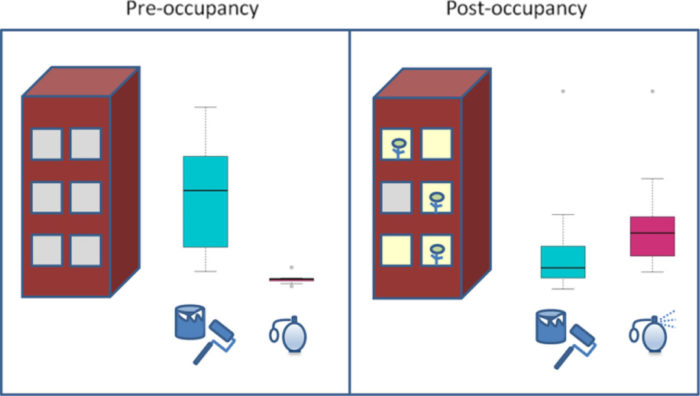

By sampling before and after the units were occupied, researchers hoped to distinguish chemicals introduced mostly by residents from those that come from the building itself.

“Our study demonstrates that residential exposure to a number of chemicals with known or suspected health effects, including anti-microbial and flame-retardant chemicals, plastics chemicals, and fragrances, appear to be predominately related to occupant behavior and product use in the home,” the study says.

Among the contaminants introduced by occupants were the anti-microbial agent triclosan, the flame retardant BDE 47, and four chemicals classified as possible human carcinogens by the International Agency for Research on Cancer. Triclosan was banned by the Food and Drug Administration in 2016 in over-the-counter soaps and body washes and is now considered “possibly toxic” to reproductive and developmental health. The presence of BDE 47 was an eye-opener because it suggests that toxic chemicals can find their way into living spaces long after they’ve been phased out by industry or government.

“Another surprising finding was the idea that people are bringing in these legacy chemicals,” Dodson said. “That’s kind of a heads up about how we deal with chemicals, that we can phase out chemicals but still find them in people’s homes 10 years later because they’re so persistent and they’re still in products.”

BDE47, a flame retardant used in upholstered furniture, was part of a family of chemicals phased out in 2005, she said, but nearly a decade later it’s showing up. How come? “One reason is persistence,” Dodson said, “and the other is that while the chemical was phased out, it’s not as if all the couches that it was added to are gone.” The furniture treated with the chemical could be going to second-hand stores where low-income families are shopping. “We are potentially just shifting a problem,” she said.

The report also flags a chemical called 23DB1P, whose “brominated tris” parent compound was banned from children’s pajamas in the late 1970s because of health concerns. It’s still used in furniture, in acrylic carpeting and sheets, and in resins and paints.

Chemicals used in beauty products and fragrances were a major source of occupant-induced pollution, while furniture, toys, and clothing all were potential sources of PVC plasticizers linked to asthma and disruptions to reproductive development in boys.

What building materials did

Given that renovations were designed to meet the LEED standard, parts of which emphasize indoor air quality and user-friendly building materials, the list of chemicals attributed to the building itself seems depressingly long.

Researchers said they were not surprised to find four target VOCs. That included cyclohexanone, which is found in products ranging from adhesives to paints and lacquers, and a phthalate called BBP that’s used in vinyl flooring and adhesives. Two chlorinated flame retardants found in sampling have known uses in furniture, but the research suggests that the insulation added during the renovation was also a possible source. One of them, called TDCIPP, was phased out of children’s pajamas in the 1970s because of cancer concerns, Dodson said, and is expected to come under tighter scrutiny by federal authorities for use in furniture.

Another compound, benzophenone, was a surprise because researchers associated it with sunscreen — something that shouldn’t have been present before anyone moved in. The finding suggests that the compound could have been used by workers in the building during the renovation, or it might have been an additive in floor finishes or paint to block UV.

The research suggests green builders and certifiers have more work to do on vetting materials. The Living Future Institute’s Red List is an attempt to keep dangerous materials out of certified homes, Dodson said, but this attention to detail is not universal.

“Green buildings provide a nice opportunity to get it right and do the best we can to reduce exposure,” Dodson said. “People are paying a lot of attention to the materials they’re selecting. So part of the takeaway is, let’s seize the opportunity to do it right and to think not only about efficiencies but also about health.”

Weekly Newsletter

Get building science and energy efficiency advice, plus special offers, in your inbox.

2 Comments

red list

This seems like a great opportunity to mention the Living Building Challenge, which prohibits the use of Red List materials. While this wouldn't solve all the problems mentioned (particularly introduced toxins), it would go a long way and further. The red list can be found on is entirety here: https://living-future.org/declare/declare-about/red-list/

Ventilation

My takeaway is that while we should do as much as possible to eliminate known pollution sources while building and re-building, we are going to want to ventilate to dilute the pollutants that seem to come from everywhere, including a lot that have nothing to do with building materials.

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in