Ventilating homes in any climate has its challenges. In Duluth, Minnesota, it’s the extremely cold weather in winter, which leads to extremely dry air when you bring it indoors. In Phoenix, Arizona, it’s the extremely hot weather in summer, which leads to higher air conditioning costs. In Santa Monica, California, it’s the extremely mild weather year round, which leads to windows getting stuck in the open position after each time the house is painted. Ventilating homes in humid climates, however, is special.

It’s the humidity. We run our air conditioners in humid climates to keep the indoor humidity at a comfortable level, below 60% relative humidity. That works great on hot days, not as well on not-so-hot days. Then, when you bring outdoor air in to reduce the amount of other people’s air you rebreathe and improve your indoor air quality, you bring in a lot of water vapor, too. On a hot day, your air conditioner probably can handle it. On anything less, it’s going to be sticky inside.

That is, it’s going to be sticky if you don’t understand the proper method for ventilating homes in humid climates. Here’s my countdown of 6 ways you can ventilate a humid-climate home. It starts with one option you should avoid, two methods that are OK if done properly, and ends with the three best options. (The numbers below aren’t wrong.)

6. Fans blowing in, out, or both

Mechanical ventilation simply means moving air with fans. A whole-house mechanical ventilation system moves air between indoors and outdoors to change the air in the house. The easiest way to provide this type of ventilation is to run fans that exhaust air from the house, supply air to the house, or both.

Exhaust-only ventilation is not a good idea in humid climates because it sucks warm, humid air into the building assemblies, which can lead to mold growth and moisture damage. Supply-only ventilation is only a little better. It does put the house under positive pressure, but you’re dumping warm, humid outdoor air right into the house. Yes, you can temper it by mixing it with indoor air before introducing it, but all the water vapor is still there.

A balanced system does both at the same rate. The lead photo shows a simple version of that type, although it’s not really an acceptable way to do long-term whole-house ventilation. The only advantage with it is that it minimizes pressure effects in the house, but you’re still putting humid air right into the house.

Pros. Cheap and simple.

Cons. Difficult to control indoor humidity.

5. Supply-only fan with humidistat

Positive pressure inside the house is better in humid climates, so the first improvement on a simple supply-only system is a supply-only system with a humidistat. The QuFresh fan by Air King and the Broan Fresh In fans do that. This kind of system allows you to set upper and lower limits of both temperature and humidity. When the outdoor air is outside the range you’ve set, the fan shuts off and waits until conditions improve to start ventilating again. Also, you can duct the supply air and dump it near a return vent so it gets conditioned and distributed to the house.

Pros. Inexpensive and simple. Doesn’t require connection with air conditioner. Better than just fans at controlling indoor humidity.

Cons. May lead to comfort problems and poorly distributed air, depending on how the outdoor air is introduced.

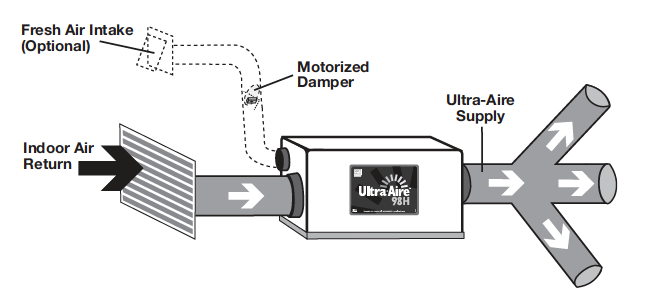

4. Central fan integrated supply

This system includes a controller, a duct connecting the return duct of the central air handler to the outdoors, and a motorized damper. You set it for how many minutes per hour you want the air handler to bring in outdoor air. When the heating or cooling system runs, the damper stays open until it hits the limit of minutes per hour. If the heating or cooling system don’t run enough, it turns on the blower, opens the motorized damper, and ventilates until it reaches the required amount of ventilation.

Pros. Inexpensive.

Cons. May be difficult to control indoor humidity on days when the air conditioner doesn’t run much. Requires connecting controlling with air handler.

3. Whole-house ventilating dehumidifier

In places like Sugarland, Texas, Kenner, Louisiana, and Sopchoppy, Florida, we often specify a ventilating dehumidifier in our HVAC design work. These units pull outdoor air in, dehumidify it, and then send the dry, fresh air into the house. We like the Santa Fe Ultra series whole-house dehumidifiers* because they’re the most efficient, made in America, and built to last. The best way to set them up is to have independent ducts, as shown below, but we do sometimes connect the ducts to the heating and air conditioning system when there’s not enough room for more ductwork.

Pros. Excellent way to control humidity and ventilate at the same time. Can be very quiet with the right equipment ducted properly. Inexpensive to operate if you choose a high-efficiency model. One piece of equipment for ventilating and dehumidifying.

Cons. High first cost.

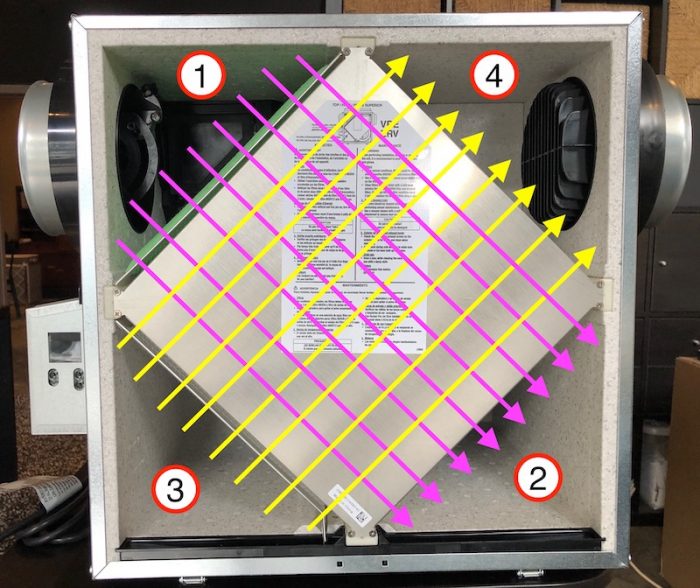

2. Energy recovery ventilator with supplemental dehumidification

An energy (technically enthalpy) recovery ventilator (ERV) has two air streams that exhange heat and moisture in a capillary core. The air streams don’t mix but allow the warmer air to give up a lot of its heat to the cooler air and the more humid air to give up a good amount of its moisture to the drier air. That way you don’t just send your expensive air outdoors without saving some of your investment. A common misconception, however, is that an ERV will reduce the humidity in a house. It doesn’t. An ERV is not a dehumidifier. It actually adds moisture to the house. It just adds less than you’d get without the recovery in an ERV. Within a year, I’ll have this type of system in my house, as I’m installing a Zehnder ERV and a Santa Fe Ultra dehumidifier.*

Pros. The ventilation happens with energy and moisture exchange, reducing the operating cost of ventilation. Excellent humidity control.

Cons. High first cost. Two pieces of mechanical equipment.

1. A conditioning ERV

Another great way of ventilating homes in humid climates is with what’s called a conditioning ERV. The CERV2 is made by Build Equinox, and their primary focus is indoor air quality. A similar system is made by Minotair. This equipment is kind of like an ERV with a heat pump, but it doesn’t have an ERV capillary core. It brings in outdoor air, exhausts indoor air, adds a little bit of heating or cooling when necessary, dehumidifies, filters, and recirculates. Read more about it in my article on ventilating with impunity.

Pros. Excellent humidity control and indoor air quality. Well-designed equipment.

Cons. High first cost. Complex equipment.

Ventilating homes in humid climates is challenging. The biggest issue is the humidity, so any ventilation system that doesn’t include dehumidification may well lead to discomfort and indoor air quality problems. The last three of the six options above are the best and all include a way to dehumidify the air.

_________________________________________________________________________

Allison Bailes of Atlanta, Georgia, is a speaker, writer, building science consultant, and the founder of Energy Vanguard. He has a PhD in physics and writes the Energy Vanguard Blog. He is also writing a book on building science. You can follow him on Twitter at @EnergyVanguard. Photos courtesy of author, except where noted.

Weekly Newsletter

Get building science and energy efficiency advice, plus special offers, in your inbox.

22 Comments

When you will be running an energy recovery ventilator and the outdoor air is 89° at 90% and the indoor air is 79° 60% what do you think the discharge air temp and humidity will be?

My wild guess is above 87.5 and 85% before the dehumidifier and 100 at 60% after.

Does anyone make a heat pump ERV that would condition the incoming air?

Walta

Walta: 89 °F and 90% RH almost never happens. Yes, it can happen, but those numbers correspond to an 86 °F dew point temperature. The US dew point record is 91 °F. More here:

https://www.energyvanguard.com/blog/make-dew-point-your-friend-humidity

Today is a humid day in the Southeast, and you can see from the dew point map below that the highest dew point on there is 77 °F. Here's the URL for the dew point map:

https://www.usairnet.com/weather/maps/current/dew-points/

Now, to answer your question, yes, the conditioning ERV does exist. See the last entry (the third number 1) of my 6 ways to ventilate.

Excellent clarification. And this is one reason I think that "5. Supply-only fan with humidistat" is a deeply flawed idea. If it's going to try to adjust ventilation based on outdoor humidity, it should be based on dew point, not relative humidity.

Ok if my 90% number is unrealistic what do you expect your discharge temp to be given Atlanta’s high today of 92° and 49%?

Walta

I would rank number 5, and possibly number 4 as well, as equally as bad as number 6. Every living space has a required minimum amount of ventilation. It's hard to put an exact number on it, but the idea is to at least try to get it right. If you allow the humidistat to just shut off ventilation and wait until outdoor humidity drops, then you've massively failed. What if the conditions don't improve for days? Absent proper ventilation, levels of air pollutants rise dramatically within a couple of hours, not days. You can't defer breathing while the humidistat defers ventilation. I think when it comes to choosing a ventilation system, the actual ventilation has to take priority over humidity. A better "bad" solution is just system 6 plus portable (or in-wall) dehumidifiers.

I imagine this question has been answered somewhere, but can someone clue me in as to how to change my shown name? I see where it's specified in my settings, but there doesn't seem to be a way to change it. It's clickable, but nothing happens when I click on it.

“[Deleted]”

I don't think we should buy into the marketing hype that calls the CERV2 and the Minotair "conditioning ERVs". If they don't have an ERV core, they aren't doing the same kind of energy recovery. They are actively pumping heat from one stream to the other, just like a heat pump actively pumps heat from outdoors to indoor. Getting energy for free in an ERV is better than having to pay for it.

Charlie,

An ERV can’t do what a CERV2 can do. Not sure I would call it marketing hype. What else would they call it? Does it cost more energy? Yes. Is it highly efficient? Yes. You can’t dehumidify for free. Does it clean the air (incoming/recirculating) and monitor CO2/VOCs? Yes. Can it be ducted with a dehu and control that and push precooled air into the dehu to further improve efficiencies? Yes. Is it very expensive? Yes but the quotes thrown around GBA that ducting an ERV is 2k are long gone and are much closer to the costs of the CERV2.

What else could they call it? A conditioning ventilator. Drop the ER from the name because that's what it lacks.

Absolutely, an ERV can't do what it does. And a CERV2 can't do all that an ERV can do. For example, if you are ventilating at a high rate in cold weather, you'll drop indoor humidity fast. An ERV adds humidity to the incoming air at extremely low energy cost. The CERV2 has an option for an output signal to turn on an external humidifier to make up for the fact that it can't do that internally, but that adds even more energy cost.

CERV2 also is able to capture humidity from my understanding. There’s nothing in the name Enthalpy Recovery Ventilator about how it’s done. The CERV2 does recover energy perhaps at a higher energy costs but also does a lot more.

It's able to remove humidity from an airstream. It can't transfer that to another air stream, like an ERV does, at least not as far as I can see from the documentation. As you say, it can do a lot of other things. If you are more interested in automated multi-function conditioning than in energy efficiency, it could be a good choice.

Excellent summary. I would add a 7th method, the lowest-tech of all: opening windows.

It has all of the problems of the first method, with none of the control! Nonetheless, it's what I'm stuck with for the next several months - maybe a year - as I relocate across the country with a family of 6 and surf across houses owned by my father-in-law, sister-in-law, and a short-term rental.

I'm moving into the short-term rental next week and am going to try to temp up a Panasonic FV-04VE1 for the children's (project conceived of here https://www.greenbuildingadvisor.com/question/homebrewed-temporary-spot-erv). If it works well I will do it for my wife's and my bedroom as well.

Hello Allison nice article. It is not clear to me how would you connect the dehumidifier and ERV with dedicated ducts for ERV or with shared ducts with heating/cooling.

Living in the Southeast (middle of NC) we experience very high humidity (regularly 77 as you mentioned) or above, w/ temps these days regularly in the 90s. We have an old leaky house built in 1921. We have a split system and set the thermostat to 75-76 but also run a dehumidifier constantly that’s set to 50%. We also have a dehumidifier in the crawl space.

Given no other envelope changes. If we were to replace the current system, what would be most efficient and effective system?

Thanks!

Seal the envelope!

So are you saying don’t invest in any of the fancy systems unless the envelope is sealed b/c they rely on a very tight envelope to do what they’re designed to do?

They will still do what they are designed to do, but it's sort of like putting a more efficient engine in a car that has the brakes stuck on. Yes, it will be more efficient, and it can overpower the brakes and move the car, but it's a bad investment compared to fixing the brakes.

Great analogy. Hopefully we can save up and do that.

Great article as always!

In my climate area we get hot humid summers and cold dry winters. We would want to have humidification in addition to dehumidification. Is the correct way of doing this having those systems in-line with the supply feed coming out of the ERV or married to the ducts coming off the A/C Air Handlers?

In theory, dehumidification is more efficient working on more humid air and so it would be better to dehumidify the supply air coming out of the ERV before it's distributed to the house. High performance commercial systems are often set up that way.

However, in practice, it's hard to maintain balance in a typical residential Erv if you have a dehumidifier connected to it, cycling on and off. Additionally, the airflow in a typical high performance the humidifier is high compared to the airflow in a typical ERV. so all those somebody very clever and might be able to figure out how to set that up, I don't recommend it and would instead recommend coupling the dehumidification to the heating and cooling air handlers, or having it separate, ducted but to fewer vents than the heating/cooling.

For humidification, it's best coupled to the heating system, because you can use the heat of the heating system to vaporize the water and get more efficient humidification that if you vaporized the water with electric heat.

But with good air sealing and an ERV, you might not need humidification, or you might just line dry some clothes inside in the coldest part of the winter.

Great article! I'm wondering if #3 is best in mild climates like Seattle. RH ranges 65-80% and mean daily temperature ranges 42-67 F. In that context, it seems like dehumidification is the driver, and not heat recovery. Thoughts?

If we were doing a dehumidifier with fresh air intake, is there any concern about consistently adding air to house and creating positive pressure? I suppose all houses leak, so we could do a blower door test and set the dehumidifier fan to a CFM that provides a balance of supply. Is that the best approach, or is there some rule of thumb that we could use in absence of a blower door test?

Finally, I'm wondering if the fan speed is variable and if the dehumidifier operates independently. It'd be nice to increase the fan speed if CO2 levels rise and to only turn on dehumidification if/when RH rises above ~50%.

Thanks in advance for fielding my questions, and for a great article and dialogue in the comments!

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in