Image Credit: Nethaniel Ealy

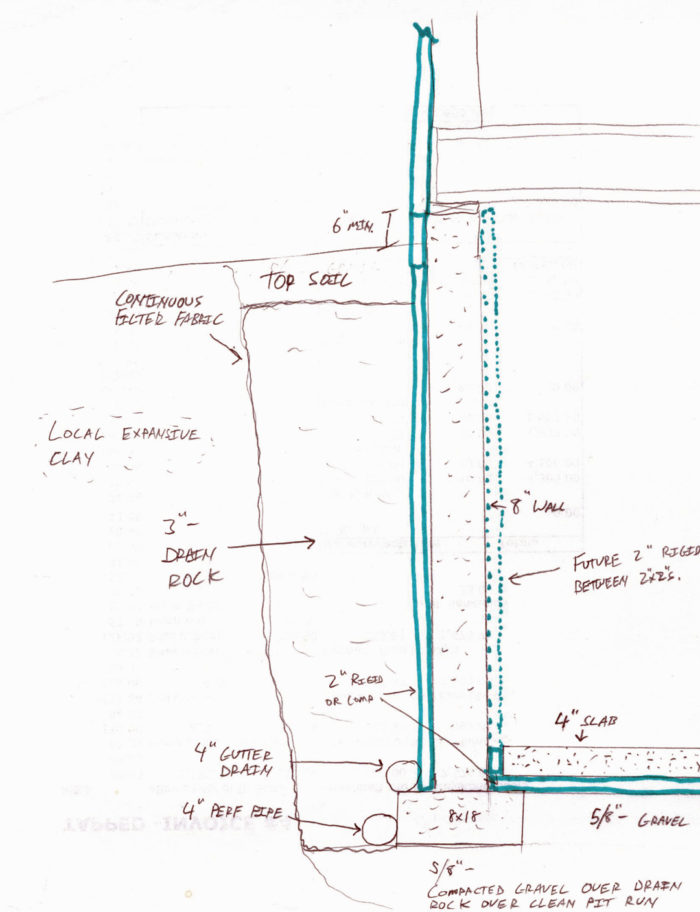

Nethaniel Ealy, a builder in Idaho who’s about to pour a concrete basement foundation, is trying to come up with insulation and waterproofing details that will be effective and within the budget.

The current plan is to place 2 inches of extruded polystyrene (XPS) on the outside of the foundation walls. At some point in the future, the homeowners would place another 2 inches of foam on the inside of the foundation walls between 2×2 studs, and then apply drywall over the studs.

When it comes to waterproofing, Ealy has a couple of choices. One is a water-based sealer applied directly to the concrete. The other is an elastomeric membrane called Colphene ICF that’s typically used over insulating concrete forms. The peel-and-stick membrane would be applied over the foam, not on the concrete.

The Colphene will add another $1,000 to construction costs, Ealy adds in this Q&A post at Green Building Advisor. Is it worth it?

He also wonders about the overall approach to insulation.

“Since the exterior XPS just terminates on top of the footing in this design and does not encapsulate the footing, how much of a benefit does it actually pass on in terms of insulation?” he asks. “Would it be better to just install 4 inches of XPS (or comparable) on the interior and forgo the external XPS layer? If so, I would also plan to skip the Colphene and just seal my foundation with a water based coating. Any flag going that route?”

Those are the issues for this Q&A Spotlight.

The plan for interior insulation is not the best

An obvious problem with the plan to add 2×2 studs and 2 inch foam on the interior of the foundation is that the foam is thicker than the studs by 1/2 inch, Dana Dorsett…

Weekly Newsletter

Get building science and energy efficiency advice, plus special offers, in your inbox.

This article is only available to GBA Prime Members

Sign up for a free trial and get instant access to this article as well as GBA’s complete library of premium articles and construction details.

Start Free TrialAlready a member? Log in

22 Comments

Termite Highway

As I have written about in previous blogs about exterior foundation insulation- make sure you do not create a highway for the termites to migrate to preferred feeding grounds- namely, your house. Personal experience discovered on a New Year's day in New Hampshire attests to their voracious appetiete for your yummy framing and even the paper backing of your sheetrock walls...

Depletion of pentane in EPS

Several years ago I read a document from an EPS manufacturer selling large slabs (a few feet thick) for use under runways & roadways discussing taking care storage & handling of freshly blown EPS for the first several days/ weeks due to the potential fire hazard. I remember being surprised to read that (even in large slabs) there would be enough pentane left to be even a remote safety issue in the field. (I'll look for it online when time allows.) To be sure, the pentane has no effect on it performance over any significant time period.

It's likely that manufacturers cutting it up into board stock of a few inches would let it outgas prior to cutting, since it would present a hazard during processing. If fabricated in thinner sheets the outgassing would be quite a bit faster.

I'd be curious to know how foil facers on polyiso affects outgassing rates. (I suspect that polyiso too is largely depleted of blowing agents prior to leaving the factory.)

retrofitting foundation insulation

Is there a GBA article on adding insulation to an existing slab? Not underneath, obviously, but vertically and along the edge to get some of the benefits of a FPSF.

Response to David Hicks

David,

As far as I know, GBA has not published an article on that topic. (If any GBA reader remembers such an article, I'm be happy if you provided a link.)

Here's a brief outline of the needed work:

1. Excavate a trench around the perimeter of your house. In a warm climate, you might go 1 foot below grade; in a very cold climate, perhaps 2 feet below grade.

2. Install rigid foam rated for soil contact (Type II EPS, Type IX EPS, or XPS) vertically up against the concrete. I would use at least 2 inches in a warm climate, and 3 or 4 inches in a cold climate.

3. Protect the above-grade portion of the insulation from physical abuse and sunlight with one of these materials:

A cementitious coating or cementitious stucco (for example, Styro Industries Brush On ST), with or without metal lath

A cementitious coating that includes chopped fiberglass (for example, Quikrete #1219 foam coating or surface-bonding cement)

An acrylic coating like Styro Industries FlexCoat or Styro Industries Tuff II

EIFS (synthetic stucco)

Cement backerboard, with or without a layer of stucco

Pressure-treated plywood

Metal flashing

A fiberglass panel like Ground Breaker from Nudo Products

Styro Industries FP Ultra Lite panels (XPS coated with mineral granules adhered to one side)

Protecto Wrap Protecto Bond (a flexible peel-and-stick membrane with a textured, gritty coating)

ProGuard Cement Faced Insulated Sheathing.

If necessary, fasten the protective material to the concrete with TapCon fasteners. (In some cases, the backfill is all you need to keep the rigid foam and protective cover in place.)

4. Install Z-flashing to protect the top of the rigid foam. The top leg of the Z-flashing should be integrated with the wall's WRB or siding.

.

Thanks Martin!

Thanks Martin!

basement walls

Check out Composite Panel Systems of Eagle River WI. These are wall panels made of composites filled with foam. No wicking, no thermal bridging, built in service cavity, strong, and come in panels up to 9x20. Put up the entire basement in an afternoon.

below grade walls

No one has addressed the problem I had in my house.

My ground floor has two below grade walls, insulated on the outside. For 4-5 months a year, I would have a regular problem with damp outside air coming in and condensing on the walls. The walls weren't cold to us, but enough below the dew point to cause a problem. I ended up insulating the inside and covering it with sheetrock. Problem solved.

Admittedly I do live in a humid environment, the southern Appalachians, but many places have this situation in the summer months.

And I would beg to differ with Peter Yost: there is still a thermal mass benefit with insulation on both sides.

Response to Gred Gross

Gred,

You didn't describe the type of insulation used to insulate the exterior of your two below-grade walls, or how thick the insulation was. Nor did you tell us whether your basement slab was insulated. Nor did you tell us whether the two other walls are framed or poured concrete, nor how these two other walls are insulated.

So there are a lot of details we don't yet know. I'll say this, however: if you had a condensation problem on your below-grade walls, either (a) the exterior insulation wasn't thick enough, or (b) there was thermal bridging at the corners of your house.

It's possible to insulate below-grade walls with enough insulation to overcome the condensation problem.

Condensation

Exterior insulation can't solve all possible condensation problems. For example, if you open the windows for 24 hours because the outside temperature is pleasant, but it's cool at night and warmer and humid during the day, you could get condensation just because the night temperature cooled the thermal mass to below following day's dew point.

Response to Charlie Sullivan

Charlie,

In theory, the situation you describe could also happen with a granite countertop in your kitchen. However, actual summer temperatures don't get cold enough for that to happen, even if you leave your kitchen windows open all night long.

The only way you get condensation on concrete surfaces in your basement during the summer is if the builder forgot to install an adequate thickness of rigid foam to separate the concrete from the cold soil.

Where would we be without granite countertops?

As Martin said in 2011, "Where would we be without granite countertops? They’re such handy devices for making almost any argument…"

https://www.greenbuildingadvisor.com/blogs/dept/musings/payback-calculations-energy-efficiency-improvements

With more details from Gred on the insulation levels and locations and particular climate, we could figure out better what happens in his case. There was a day in Sept. here in New England when the daytime dew point was more than 20 F above the preceding overnight temperature, but that was cold enough (40 F) that even Vermonters would close the windows. Further south, there might be similar fluctuations in a temperature range where open windows would be more appealing.

condensation

I have 2" of blueboard outside, and 2 " under the slab. The other walls are wood framed, with south- (and west) facing window and doors.

Yes, we often have days and nights with 100% humidity in the summer times, and when we would leave the doors open at night, the walls, which kept the rooms comfortable in the daytime, would collect dew on them. No granite counter-tops to test here, but I still feel that the thermal mass effect is still there, even with insulation, hence the slower change in temperature which led to the condensation.

Insulated Concrete Form (ICF)

From what I have read, it seems to me that Insulated Concrete Forms are the way to go when installing a new basement. Kills two birds with one stone.

Gred's Appalachian Condensation

Gred,

Dew point calculations only work when you assume the interior temperature is constant and also at a constant humidity. If you are leaving the doors and windows open, and the block wall is in contact with the ground (or not), it will always sweat any time it is colder than the dew point, just like rocks sitting outside on foggy mornings.

Ambient temperatures can move your wall temp colder than the dew point overnight, and then the dew will collect there as the humidity rises as the sun comes up, just like on the ground on many beautiful mornings.

Your options are to close the windows or insulate the wall on the inside. The exterior foam is not protecting the wall from cooler ambient temperatures you are letting in through the windows.

Hope this helps! There is also a handy program called the 'climate consultant' from the folks at UCLA and the California Energy Commission that can put together a psychrometric chart, and display ground temperatures as well. Ours swings above 50 in july and below 50 in december. Asheville ground temperatures nearby are nearly 10 degrees warmer every month and swing up in may instead of july. That gives you plenty of months for condensation potential with the windows open when the relative humidity never goes below 60%.

-Q

ICFs are wasteful as much as

ICFs are wasteful as much as this idea, don't waste

your time and $

This is an old article, however, I would like to add my two cents.

Maybe I missed a newer one, but this doesn’t speak to Vapor permeable at all.

We are in zone 7a and are adding 2” of gps to the exterior of a poured concrete foundation. Interior, we will be spraying 2” of closed cell foam, and then a 2x4 batt wall. This gives a nominal r value of approx r37.

The spray foam is .97 perm, so falls under class 2 Vapor retarder I believe.

There really is not a lot of information about insulating both sides of a concrete foundation. Maybe because icf is so prevalent or because it’s an undue cost below grade?

Thoughts?

danielelh,

You may find these articles useful:

https://www.greenbuildingadvisor.com/article/three-ways-to-insulate-a-basement-wall

https://www.greenbuildingadvisor.com/article/how-to-insulate-a-basement-wall

Hi Malcolm, Thanks for the links, however, none of those speak to the issue that I raised about exterior insulation, and how to finish on the inside. Do we want to seal? Do we want to breathe to inside? Joe Lstiburek recommends letting it breathe to the inside, but many others have spoken against it as we don't want an easy way for moisture to get in to the basement of a house.

Have you ever seen an article or detail speaking about that?

danielelh,

The addition of exterior insulation just raises the temperature of the inside face of the concrete stem wall, meaning it needs less interior impermeable insulation to avoid moisture condensing on it. That you are also insulating the outside doesn't change how you should treat the layers inside. I would take the advice on permeability from the first article (and the subsequent comments). My take is that the assembly you are proposing will perform well without additional layers.

Dr. Lstiburek recanted his advice and now says that foundations don't need to dry to the interior. I can't find a white paper but here's an article that mentions it: https://www.greenbuildingadvisor.com/article/joe-lstiburek-discusses-basement-insulation-and-vapor-retarders.

When talking about vapor concerns, it helps to use precise language. "Breathing" can mean many things. I believe your question is whether you want the foundation assembly to be vapor-permeable to the interior. I use similar rules as for above-grade walls, found in IRC table 702.7.1: https://codes.iccsafe.org/content/IRC2015/chapter-7-wall-covering#IRC2015_Pt03_Ch07_SecR702.7 to prevent condensation concerns. As for inward moisture movement, I would only finish a basement if I had an excellent exterior drainage strategy--preferably a combination of waterproof elastomeric membrane and a dimple mat.

Oh boy. That's an issue. Lol. Thanks @Michael Maines for clearing that up.

We're in Winnipeg, heavy clay, Bluesking and 2" subterra, and have weeping columns that help alleviate hydrostatic pressure should we ever need it without overwhelming the sump pumps. Inside, we were debating 2" of rigid foam (interra) with strapping or 3" of spray foam into an empty cavity frost wall 1" off the foundation. Client wants outside walls finished, which mean we have to bring electrical to code and cover any foam. (unless the new resistant foam, I forget what its called at the moment).

Thanks again for the links and for the info.

In my area, "frost wall" is synonymous with stem wall. I think you're talking about potentially building a framed wall on the interior? If your goal is to finish the space with drywall or similar, that's a good option, though I often do a layer of rigid polyiso foam for condensation control and then fill the cavities with cellulose.

If the space is to remain utilitarian, I use Thermax rigid foam with a white foil facing; it's clean, bright and finished-looking and has a fire rating so no additional covering is needed.

Log in or become a member to post a comment.

Sign up Log in