Image Credit: Image #1: National Academy of Engineering

Image Credit: Image #1: National Academy of Engineering This "thermal comfort station" consists of three air temperature sensors and a mean radiant temperature globe (the black sphere in the middle of the station).

Image Credit: Image #2 and Images #6 through #15: Peter Yost The Extech HT200 device includes an MRT globe as well as sensors to measure several other thermal comfort metrics.

Image Credit: Image #3: Extech Howdy Goudey used two temperature sensors and a plastic plumbing float (painted matte white) to build this MRT unit. The two sensors connect by serial cables to a Hobo data logger.

Image Credit: Image #4: Howdy Goudey M.A. Humphreys from the Building Research Establishment in Watford, England, illustrates a very simple MRT globe made from a regular fluid-filled thermometer and a painted ping-pong ball.

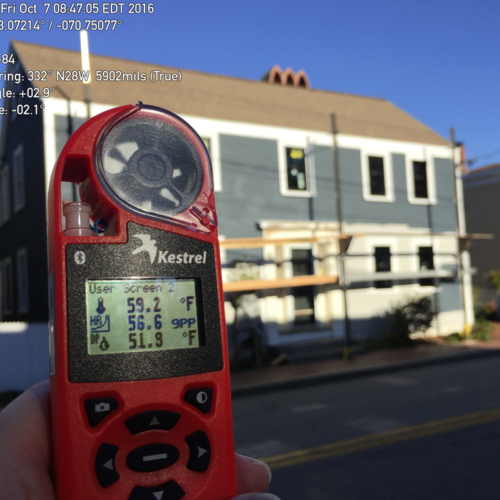

Image Credit: Image #5: M.A. Humphreys I chopped off the bottom of my $7 hardware store spirit-filled thermometer, drilled a hole in a ping-pong ball just big enough to get the bulb through, sealed the bottom of the ball with tape, and then spray painted the ball flat black. I tested three MRT globe devices by lining them up about 2 inches away from a small radiant heating panel. My digital infrared thermometer shows that when fully energized, the radiant heating panel has a surface temperature of 141°F. Pictured here is the top Hobo data logger recording the background air temperature and relative humidity. The bottom logger is measuring the air temperature right next to the MRT globe on channel 1 (on the left) and the MRT globe on channel 2 (on the right). At 11:45 a.m., just prior to the test, Goudey’s MRT globe is reading just under 62°F. At 11:45 a.m., just prior to the test, the Extech HT200 is reading 63.5°F. At 11:45 a.m., just prior to the test, my do-it-yourself MRT globe is reading just about 60°F, but the scale of the thermometer might be misaligned. It's possible that when I modified this thermometer by sawing off part of the backboard plastic panel with the numbers and gradations on it, I did not get the thermometer back in exactly the right place relative to the scale on the plastic background. After the radiant panel was energized, my do-it-yourself MRT globe is reading just between 75°F and 76°F. Goudey’s MRT globe is reading just below 75°F. The Extech HT200 globe is reading 74.8°F.

All the way back in 1993, one of my first research projects at the NAHB Research Center was assessing the performance of radiant ceiling panels for the Department of Energy’s Advanced Housing Technology Program. (The final report was titled “An Evaluation of Thermal Comfort and Energy Consumption for the Enerjoy Radiant Panel Heating System.”)

I really knew next to nothing about the science of thermal comfort. I distinctly remember the first time I heard the name Ole Fanger. Dan Cautley, a mechanical engineer who was my NAHB Research Center mentor (and subsequently a lifelong friend), handed me ASHRAE Standard 55 – Thermal Environmental Conditions for Human Occupancy and said, “Study this and come to love Ole, the father of measuring thermal comfort.” (The photo at right of Ole Fanger is from a tribute to Fanger and his work.)

Ole Fanger’s work and ASHRAE Standard 55 both focus on the six factors determining thermal comfort:

- air temperature (AT)

- mean radiant temperature (MRT)

- air speed (AS)

- relative humidity (RH)

- metabolic rate (unit of measure: met)

- clothing insulation (unit of measure: clo)

The first four factors are environmental conditions and the last two are personal factors. And if the last four are in a “typical” range for a commercial office setting — roughly, little to no air speed, RH between 25% and 55%, people seated at their desks (so having a low metabolic rate and dressed for work) — we can characterize thermal comfort just by measuring air and mean radiant temperature, adding them together and dividing by two. This is called the “operative temperature.”

An MRT globe measures mean radiant temperature

A thermal comfort measuring station is pictured in Image #2 (below). It consists of three air temperature sensors (located at different heights) and a mean radiant temperature (MRT) globe positioned at about the height of a seated person. The MRT globe is a 6-inch hollow copper sphere with a temperature sensor located in the center of the sphere.

You can purchase devices that measure MRT along with air temperature and relative humidity — for example, the Extech HT200 pictured in Image #3. But the HT200 costs about $250 (retail price). Is there an easier — and more affordable — way to measure MRT, which is so critical to assessing thermal comfort?

My colleague and friend Brian Just from Efficiency Vermont let me borrow his Extech HT200 so I could compare a couple of “homemade” globes and see how they did.

Making your own MRT globe

Image #4 (below) shows an MRT globe built by my good friend Howdy Goudey from the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. Howdy has a reputation as an engineer who can build just about anything; Howdy let me borrow his do-it-yourself MRT globe to test it against the Extech HT200.

But I wanted to go even lower tech, so Howdy referred me to a 1977 research paper by M.A. Humphreys: “The Optimum Diameter for a Globe Thermometer for Use Indoors.” This paper includes an illustration of the simplest, cheapest MRT globe ever (see Image #5).

The required parts include a ping-pong ball and a mercury thermometer. It’s hard these days to come by mercury thermometers, so I thought I would try a “spirit-filled” thermometer which cost about $7 at a local hardware store (see Image #6).

Testing a homemade MRT globe

Image #7 is a photo of a test I performed. I lined up the three MRT globe devices and then placed the fully energized radiant panel (Image #8) just behind the devices and recorded how well they tracked each other and if they responded within the same time frame. I figured that if either or both of the do-it-yourself MRT globes were even close to the Extech HT200, that would be terrific.

Image #9 shows how I tracked the background air temperature as I tracked the devices being closely exposed to the heating panel.

Before being exposed to the radiant heating panel, the Extech HT200 and Goudey’s MRT globe were reading within about a degree and a half of each other (see Images #10 and #11). My do-it-yourself MRT was reading just about 60°F, lower than either of the other two devices (see Image #12).

Images #13, #14, and #15 show the temperature readings for each of the devices as they reached peak radiant temperatures with the 141°F radiant heating panel just 2 inches behind all three devices. Good news! All three devices are reading within about 5 F° of each other. And in terms of speed of response, the Extech HT200 and my do-it-yourself device responded pretty much equally fast to the radiant heating panel, with Goudey’s MRT globe taking up to 2 minutes longer to “catch up” with the other two.

The Goudey MRT is the largest of the three devices, and that may explain its slower response time. Don’t be fooled by the matte white color of the Goudey globe compared to the matte black of the other two. Color only matters with shortwave IR, which only happens with radiant exposure to something like the sun; Goudey only uses his MRT globe for indoor settings. And as a heat stress device, the Extech HT200 gets used outdoors quite a bit. Inside buildings, only lower energy, long-wave IR is generated, and color does not matter.

Conclusions

My little test suggests that a do-it-yourself MRT globe built out of a spirit-filled thermometer, a ping-pong ball, and some matte or flat spray paint will do just fine.

I bet Fanger would be proud. You can build your own MRT globe and use it to work with clients to demonstrate how air temperature and MRT affect thermal comfort.

In addition to acting as GBA’s technical director, Peter Yost is the Vice President for Technical Services at BuildingGreen in Brattleboro, Vermont. He has been building, researching, teaching, writing, and consulting on high-performance homes for more than twenty years. An experienced trainer and consultant, he’s been recognized as NAHB Educator of the Year. Do you have a building science puzzle? Contact Pete here. You can also sign up for BuildingGreen’s email newsletter to get a free report on insulation, as well as regular posts from Peter.

Weekly Newsletter

Get building science and energy efficiency advice, plus special offers, in your inbox.

11 Comments

operative temperature

I recommend an experiment. Face a single pane window on a cold day. Now turn around. MRT and air temperature didn't change - but comfort will.

The calculator here is interesting:

http://www.healthyheating.com/solutions.htm#.WuHX8HUbOUo

Jon R

Jon,

Your experiment works better for people who (a) have no facial hair and (b) have plenty of hair at the back of the head.

If you are a bald man with a bushy beard, the results may be the opposite of the results for a clean-shaven person with a full head of hair.

Nice picture

And I thought that was your new headshot Peter.

Great Timing!

I had done a pile of reading about MRT when I was studying radiant heating for our build. Even though we most likely won't be relying on radiant heating for the bulk of our heat load, knowing how to DIY a globe thermometer will be really handy! I was debating the Extech (or a cheaper version) and not able to justify the investment.

One point I'd like to make about the short vs. mid and long wave IR. It's worth noting that ALL of the MRT globes I saw when researching them were matte black. True, many are intended to cover outdoor usage, but given the choice I don't see why you would paint it white? If solar radiation is present in a room that would certainly contribute to the MRT. Perhaps I'm missing something? Perhaps the white globe in this test being slow to respond has something to do with its color?

A 40mm ball plus direct

A 40mm ball plus direct reading of a thermometer inside approximately yields a human comfort value. Typically this won't be the same as MRT. For that you would need to adjust the thermometer reading for convection effects (diameter, etc)

Healthy Heating

I don't think any discussion of MRT is complete without acknowledging the ongoing work by Robert Bean at Healthy Heating (healthyheating.com), especially his excellent comfort predictor tool - http://www.healthyheating.com/solutions.htm#.Wuog9_ZFz5o

Robert Bean and Healthy Heating

Point well taken - Robert Bean and his work on thermal comfort from a combined engineering and full spectrum of comfort is seminal. Thanks for recognizing him and his work.

I recognize this post is 2 years old but in 2020 I do not see the images that are referred to in the article. Sigh...

Gary,

To see the images, click the green rectangle at the top of the article -- the one labeled "View Gallery."

He might be referring to the notion that there is a link describing 15 images while the gallery displays two.

Andy,

On my computer, the "View Gallery" link displays 15 images.

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in