You know that old saying, “No good deed goes unpunished”? It applies to a lot of homes with respect to ventilation. If you simply bring outdoor air into the house, you pay for it . . . in more than one way. The outdoor air you bring in is unconditioned so you have to heat it or cool it. If you’re in a humid climate, you may have to dehumidify it. If you’re in a dry climate, you may need to humidify it.

Depending on how you introduce the ventilation air into the house, you may have cool drafts in winter or warm air blowing on you in summer. Then there’s the issue of ventilation causing moisture to get into building cavities, where it can wet the building materials, cause decay, and grow mold. And if you want to increase the ventilation rate, you get punished even more.

The most common types of whole-house ventilation systems use the exhaust-only or supply-only strategies. Exhaust-only ventilation uses fans that are already in the house—bath fans and range hood—with controls to modulate the rate or runtime to provide the required amount of ventilation air. Supply-only ventilation may use dedicated fans that blow air into the house, the blower in the heating and cooling system, or a ventilating dehumidifier. Both strategies can create problems with comfort, energy use, or moisture if you try to increase the amount of ventilation air too much.

But there are ways to ventilate a house at higher rates and not have problems. You just need to use a different strategy. Let’s look at three ways you can do this.

Balanced ventilation with heat and moisture recovery

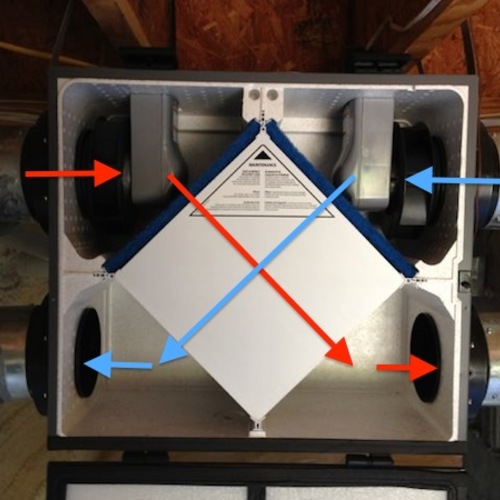

The best way to bring outdoor air into a home is to do it with a balanced ventilation system that has heat recovery (everywhere) and moisture recovery (most homes). You probably want an energy recovery ventilator (ERV) that does both heat and moisture recovery rather than a heat recovery ventilator (HRV) that does only heat recovery, but that’s the subject of a future article. Here let’s just focus on the ventilation.

Bringing outdoor air into the house dilutes indoor air pollutants. By doing so continuously, you can keep those pollutants at a low level. Carbon dioxide levels are a good measure of how much air exchange you’re getting. But, as mentioned above, bringing in outdoor air comes at a cost. With heat and moisture recovery, though, that cost is much lower. (From here on, I’m going to use ERV to stand for both ERV and HRV. If you’re one of those weirdos who uses HRVs, you can make a mental substitution when you read ERV.)

An ERV doesn’t let your expensive, conditioned air just leave the house. Just as you’re required to turn in your shoes before you leave the bowling alley, an ERV makes outgoing air turn in its heat and moisture in winter. And just as Buster Scruggs had to deposit his guns—including the señorita pistols—when he entered the saloon, the fresh air entering the ERV in summer deposits its heat and moisture into the outgoing air.

Those heat and moisture exchanges eliminate or reduce a couple of the costs you have to pay for ventilation. By recovering heat and moisture, you have to do less conditioning of the ventilation air once it’s inside. The heat and moisture exchange also brings the ventilation air close to indoor conditions so comfort problems are less likely. The equal air flows of exhaust air and outdoor air reduce the likelihood of moisture causing trouble in the building enclosure.

In short, if you want more ventilation air in your house without having to suffer the ventilation penalty, an energy recovery ventilator can do that for you. Just make sure to get one that has a high efficiency of transferring heat and moisture, electronically commutated fan motors, and a MERV-13 filter on the incoming air side. (Some of the brands we like are Broan, Fantech, Panasonic, Renewaire,* and Zehnder*.)

With such a ventilation system, you may be able to crank it up to half an air change per hour or more, which is about twice the ASHRAE 62.2 rate. Because of the space needed and upfront costs, going higher than that is hard to do, but you can certainly get more equivalent air changes per hour, ACHe, by combining ventilation and filtration.

Balanced ventilation combined with a heat pump for recovery

Another way to get more ventilation air into your house is to use a ventilation system that has a built-in heat pump. I’ll call it a heat pump ventilator. Instead of a heat exchanger core as the ERV has, this device uses the heat pump to transfer heat between the air streams. Currently, you have two options in North America for this kind of ventilator: the CERV-2 by Build Equinox and the PentaCare V12 by Minotair.

The heat pump gives this device the ability to do heating, cooling, and dehumidification. They don’t provide much heating and cooling capacity since their main purpose is to provide clean air. The CERV-2 has a heating and cooling capacity of about 3,000 BTU per hour. The PentaCare V12 provides about 6,000 BTU per hour of heating capacity and 11,000 BTU per hour of cooling capacity.

Another difference between an ERV and a heat pump ventilator is that heat pump ventilators also recirculate air in the house to provide more filtration, heating, cooling, or dehumidification of the indoor air. This combination of ventilation and filtration with high-MERV filters can provide another level of cleaning the air. Both are important.

The heat pump ventilator eliminates some of the penalties associated with ventilating at higher rates: comfort and durability. But unlike the passive heat exchanger in an ERV, the heat pump does use energy. The heat pump ventilator, as a result, will cost a bit more to run than an efficient ERV but you should see lower ventilation costs than with exhaust-only or supply-only ventilation systems.

Supply-only ventilation with a ventilating dehumidifier

In hot-humid climates, your best bet is probably a ventilating dehumidifier. When outdoor dew points are 75 to 80 degrees Fahrenheit for many months and you even use the air conditioner in January, this method will allow you to ventilate at higher rates without the humidity. This requires a ducted dehumidifier that pulls some air from the conditioned space and some air from outdoors. Ultra-Aire is the brand we like.

With the proper controls, a ventilating dehumidifier can run with or without the compressor on for dehumidification. With the compressor off, you can ventilate without dehumidifying. You could also put an electronic damper and controls on the outdoor air duct to dehumidify without ventilating.

All three of the methods described above allow you to crank up the ventilation with impunity. OK, maybe you don’t get complete impunity but you’ll certainly get a lot less punity.

_________________________________________________________________________

Allison Bailes of Atlanta, Georgia, is a speaker, writer, building science consultant, and founder of Energy Vanguard. He is also the author of the Energy Vanguard Blog and is writing a book. You can follow him on Twitter at @EnergyVanguard.

* Disclosures: Renewaire and Zehnder have provided one each of their ERVs to Energy Vanguard.

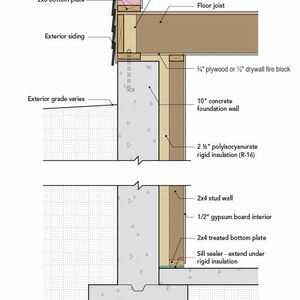

Photo credits: Lead photo of Zehnder HRV by Albert Rooks of Small Planet Supply, used with permission. CERV-2 photo from Build Equinox, used with permission. Ultra-Aire dehumidifier photo by Energy Vanguard, used with impunity.

Weekly Newsletter

Get building science and energy efficiency advice, plus special offers, in your inbox.

24 Comments

The third option is the Messana Air Treatment Unit (ATU) also a combination HRV / dehumidifier that operates isothermally using a loop off a buffer tank for either the preheat or cooling. That allows you to use one heat pump for heating, cooling and DHW,. That allows us crazy hydronic types to have radiant heating and cooling without worrying about condensation. That unit is based on the Emerson line of HVACR controls.

When the book is done, an article on ventilation controls would be useful. Most of the system identified above are controlling ventilation by measuring CO2, temperature and RH. That should save energy.

The problem in the HVAC industry is poor controls that don’t integrate with lighting and security systems. When I open my windows, the control system should turn off the ventilator; when I turn on the stove fan the control system should turn on the makeup air and dehumidify it if necessary.

William, there's another one called Ephoca, too. From what I understand, it's going to be listed in the US in a few months.

Yes, controls are a huge issue for ventilation as well as heating & cooling.

Very informative article. I am wondering about the infiltration dynamic for a home, heating vs cooling. In the heating season the stack effect is a major player in the amount of infiltration and the leakage areas. Air goes out high in the building envelope and is replaced by air coming in at lower points. How does air move into a home in cooling mode? Warm to cold so outside air is coming into the building, is it stack effect in reverse?

From how I understand stack effect its driven by a temperature difference, and thus is most potent during the coldest days of the winter, and the hottest days of the summer. In a colder climate winter will likely have a larger stack effect due to the larger temperature differential. Given its a physics phenomenon I would venture that the 'direction' of the gradient shouldn't matter. Another factor is the height of the building as well, the taller the structure, the larger the effect can be. Should my comment be wrong I'd be happy to be corrected!

I would theorize that regardless of the direction of air flow, it would be using the same holes in the envelope to enter or exit the building.

In summer, with an air-conditioned interior, stack effects is in reverse. So hot humid air from the attic leaks through the can-light penetrations from the attic into the master bedroom, pushing the cool air from the A/C vents down into the lower levels, and out leaks in the basement. The residents notice that upstairs, particularly the master bedroom, is to cold and call an HVAC company to complain. They put in a bigger central air conditioner, or add a second one installed in the hot attic, so now the master bedroom is noisy, but still gets hot and humid when the oversized A/C cycles off.

Doug, yes, in summer the stack effect moves in the other direction. Here's an article I wrote about it nearly a decade ago:

https://www.energyvanguard.com/blog/Heat-Rises-and-Falls-Stack-Effect-Air-Movement-Heat-Flow

> Carbon dioxide levels are a good measure of how much air exchange you’re getting.

Only if you know how many people are present, for how long, how active they are and the outdoor CO2 level. And even then it doesn't tell you if you have a VOC or PM2.5 problem.

ASHRAE agrees: "CO2 concentration is not a good indicator of the concentration and occupant acceptance of other indoor contaminants"

I suggest "high carbon dioxide levels are a useful but insufficient indicator of inadequate air exchange".

An effective way to increase ventilation efficiency is zoning - don't ventilate when/where it isn't needed.

Jon, I think most people know how many people are in their home at any given time. And outdoor CO2 levels are around 400 ppm. If a family of 4 is at home having dinner and the CO2 level is 1,500 ppm, it's pretty clear they aren't getting enough air exchange.

Your quote from ASHRAE is about other indoor air pollutants, and I didn't make any claims about CO2 telling you about your overall IAQ.

I'd love to see some analysis comparing the energy requirement to maintain the same indoor conditions using each of these, in combination with the same air conditioner in each case. The active ones require the air conditioner to do less work, but they use energy. The question is whether they save enough of the work the A/C has to do to be worth the energy they consume.

How's the Zehnder install coming along Dr. Bailes?

Seems like a Zehnder ERV installed in Climate zone 3A (Atlanta- yes?) might have a long payback time compared to say, a couple of Broan Smart Sense fans, and a dedicated/dampered fresh air supply?

Regarding Buster's decision to enter the Frenchman's Gulch "ERV" and deposit his pistols, I would argue that it was also expensive- not only to Surly Joe, but ultimately to the San Saba Songbird himself (also known by other nicknames, appellations, and cognomens), since upon leaving the saloon, he was soon reminded that "you can't be top dog forever". ; )

Karl K

Karl, I'm glad to see I'm not the only one who enjoyed that fine Coen Brothers film!

John, it's coming along slowly. My first priority right now is finishing the book (in addition to keeping Energy Vanguard going), so I do a little when I can on weekends. I've installed some of the vents in the ceiling so far.

How does pricing compare for these options? Are they considerably more expensive than what is seen in new construction homes?

JWolfe1, that depends on what you mean by "new construction homes." If you're talking about spec homes, then yes, the strategies I described above all cost in the thousands of dollars rather than hundreds or less. Many new homes get no whole-house mechanical ventilation at all. In Georgia, home builders flexed their muscle and got the state to change the airtightness needed for mechanical ventilation from >5 to >3 ACH50.

On the positive side, you can find a good ERV for about $1,000. If you need only one and are installing it yourself, you can have whole-house balanced ventilation with recovery for about $2k or less (in a smallish house).

Allison, would you outline a configuration that results in a self-installed system for ~$2000? Unless one has existing ductwork that can be repurposed for (or else tied into) with the ERV, I don't see how it's possible. And reusing ductwork seems like poor practice for this purpose.. Thanks.

Most of the comments regarding the CERV on this site seem to be pretty negative although I haven’t seen many from actual users.

I might be one of the ones who comes across as negative about it. Just to be clear, I have no doubt that it works. My only complaint is the lack of evidence that it is any more energy efficient than a more conventional configuration.

I cannot tell you how much energy it uses. I would love to put in an power monitor at the panel box, but the one that I like requires internet and i live in a near dead spot and i am not willing to pay Spectrum $10k to have them run a line, but i digress.

I can tell you that i haven't had to run my mini split since the Polar Vortex broke down in Feburary, except for a few hot days in June.

I know that the unit can heat and cool a little, but the most important thing is that removes the humidity.

Steve Young

Will; I have had a CERV in my home for 3 1/2 years. I just missed the transition over to the much more elegant CERV 2.0. The 1.0 version looks like a DYI project, unfortunately.

It has worked flawlessly for that time.

The only issue that I have had has been condensation on the cold side ductwork. (There really needs to be better insulated ductwork available in this country) I ended up wrapping the joints in flashing tape and add7ng more flexible foam insulation. This, of course, has nothing to do with the CERV design.

Otherwise, it does what it is supposed to do, with little fuss and a little maintenance.

Steve Young, Lancaster OH

Thanks Steve. I’ve got an old house with little to no area to put ducts in (going ductless for HVAC). Weighing my options for ERV which can also filter well (MERV 13+).

Can anyone recommend a handheld measuring device for IAQ - more than just CO2 levels? Allison recommended Awair AQM8002 and Aranet 4 for CO2 on his blog, but looking for more than Temp/RH/CO2 - unless an accurate device is cost prohibitive.

Hi David,

I may be misunderstanding the “handheld” part of your search, but as far as mobile/moveable (as is you could put them in a bedroom one day, then the kitchen the next) I’m unaware of a well regarded unit that does everything.

I do some work at Boise State University that deals with wildfire smoke and IAQ, and the Purple Air II is what’s used for both indoor and outdoor PM2.5 sampling. It’s not super apparent on their site, but you can use that same monitor indoors and out, and there is a complementary model that uses an SD card if internet connectivity is an issue.

For VOCs/CO2 and radon, I use the AirThings Wave+. It also does temperature and RH, but for the latter I prefer Govee’s wireless temp/RH sensors as their price point allows for multiple locations to be monitored and compared. Hope that’s helps!

Hi Alison (and All),

Wondering what balanced ventilation option you'd recommend for very small, to tiny house sized homes in northern climates. I'm in the process of pondering a few "under 600SF" new construction cabins and don't want to over or under ventilate. All buildings will be super insulated, all electric, with ductless mini-splits for heating and cooling, and include a small output simple range hood, vented to the outside, ( the way God intended : ) It looks like Panasonic now have some very dinky ERVs. Wondering if those might be appropriate and cost effective for "tiny homes".

Thanks for any input you have!

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in